In general, reality television has been a plague upon the earth. From the Kardashians to The Bachelor, the genre’s sins are manifold. But there’s one exception that proves the rule: MythBusters, the strange cross between Mr. Wizard and The Real World.

Neither Jamie Hyneman nor Adam Savage are what you would call TV star material. Hyneman has had an amazing series of jobs, including Caribbean divemaster and builder of fighting robots. His special effects company M5 provided the base for the show. Savage was a prop maker who worked on the Star Wars prequels and The Matrix. The Discovery Channel show takes legends big and small and puts them to the test using science. If you dropped a penny from the Empire State Building, could it kill a pedestrian? (Answer: No) Could Archimedes have created a sun-powered death ray in Iron Age Greece? (Answer, after three attempts: No) Which is more fuel-efficient, driving with the windows down or with the AC on? (Answer: It depends on how fast you’re going.)

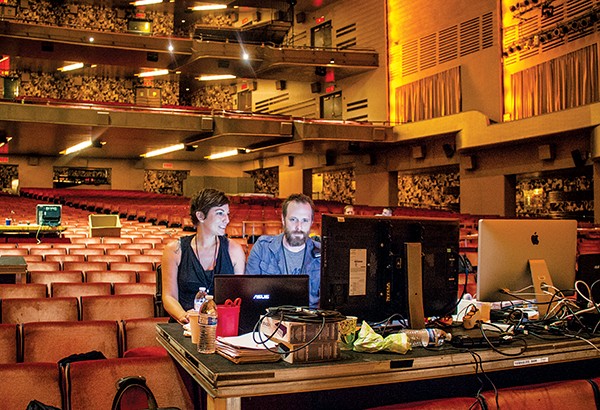

Jamie Hyneman

What’s special about MythBusters is its philosophy. It’s one of the only places on television that shows how science works. MythBusters demonstrates that science is a process. By focusing more on the way the questions are asked and tested than on the sometimes rocky relationship between the hosts, the show inspired a generation of kids to become interested in science and technology.

It should be common knowledge by now that most reality shows are not “real.” From Honey Boo Boo to Survivor, the writers and producers come up with story lines and coach the untrained actors into manufacturing conflict and chasing the whims of the audience. For MythBusters, the central experiments are always shown as is. If one of their jury-rigged, Rube Goldberg-esque contraptions blows up, they show it. As Savages’ saying goes, “Failure is always an option.” In science, you learn just as much from a failed experiment as from a successful experiment is a powerful sentiment that goes against so much of our success-oriented society.

MythBusters is still a TV show, so the visual icing on the cake is the explosions. If a myth involves something blowing up, all the better. Among the biggest surprises the show has revealed is that hot water heaters make spectacular explosions, but military explosives aren’t very interesting to look at. This is the value of science.

Savage and Hyneman developed a connection with their legion of fans, and in the wake of the announcement that the 2016 season will be the last, they are doing a victory tour, which will land at the Orpheum Theatre this Saturday, November 14th for a bittersweet evening of science and, probably, explosions.