Early numbers indicate that last weekend’s Super Bowl matchup between the New England Patriots and the Seattle Seahawks drew 114 million viewers, making it, in terms of raw numbers of viewers, the most-watched TV show in history. Most of us viewed the game on NBC, either via their cable service or over-the-air broadcast. But for the first time, 1.4 million people watched the game streamed on the internet by YouTube. It was a move that the networks had been resisting for years, and an admission that the TV industry is in the early days of a profound revolution.

Another sign of change afoot could be seen at the Golden Globe awards, where Transparent won both Best Comedy or Musical Series and Best Performance for its lead actor Jeffrey Tambor. The unusual part is that Transparent was made by Amazon.com, and streamed exclusively on their Prime Instant Video service.

The Man in the High Castle

The show was a product of the second Amazon Pilot Season, a unique experiment in TV production that has so far been bearing fruit for the internet giant. Usually, a TV network will take pitches from producers and then order pilot episodes of several different shows each year. Then the network brass will pick what they think are the best two or three shows and pay for entire series. It is a notoriously wasteful process that yields questionable results.

But once Amazon got into the content-production business, they decided to show all of the pilots they order, and then ask the audience which ones should become series. It highlights a couple of important differences between the business models of traditional TV channels and the upstart internet producers. NBC, CBS, ABC, and FOX make money by using their programming to sell advertising, so that means their real customers are the ad buyers, not the viewers. Amazon, Netflix, and HBO are in the business of selling subscriptions, which means their primary customers are the viewers themselves. Without the fear of alienating advertisers and without the constraints of a schedule, they are freer to develop productions the networks would deem too risky.

This year’s crop of Amazon pilots includes The Man in the High Castle, an adaptation of a classic science fiction novel by Philip K. Dick produced by Ridley Scott. The premise of the 1962 Hugo Award winner is simple: What if the United States had lost World War II? In Dick’s alternate history version, the Greater Nazi Reich now rules the East Coast, while the Japanese Pacific States occupy the West Coast. Between them is a semi-lawless Neutral Zone, occupied by refugees deemed undesirable by the two Axis powers: Blacks, homosexuals, Jews, and other untermenschen.

The first of the series’ twin leads are Joe Blake (Luke Kleintank), a young New Yorker setting out cross country on his first mission for the beleaguered resistance. The second is Juliana Crain (Alexa Davalos), a San Franscisan first seen taking Aikido lessons and fending off the advances of her Japanese instructor. Crain’s boyfriend, Frank Frink (Rupert Evans), works in a factory making fake antiques to sell to the Japanese. His co-worker Ed McCarthy (Hustle and Flow‘s DJ Qualls), is a gossipy source with the latest news from inside the Reich. It seems the now elderly Hitler is at the end of his life, and when he dies, his successor will most likely declare war on the Japanese and claim the entire continent.

Dick’s strongest suit was always his elaborate world-building, and the show’s impeccable production design is rich with detail. Supersonic Nazi rocket planes land in San Francisco at Hirohito International Airport. Newsreels depict happy white Americans working in Volkswagen factories in Detroit underneath a flag whose 50 stars have been replaced with a single swastika. The taut pacing and slowly building tension is reminiscent of Battlestar Galactica at its best. The characters, which also include an I Ching-obsessed Japanese embassy official played by Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa, all show promise, even if the acting was a bit stiff in this pilot episode.

Ambitious and brainy, The Man in the High Castle is unlike anything else on television, and a good argument in favor of the Amazon way of doing things.

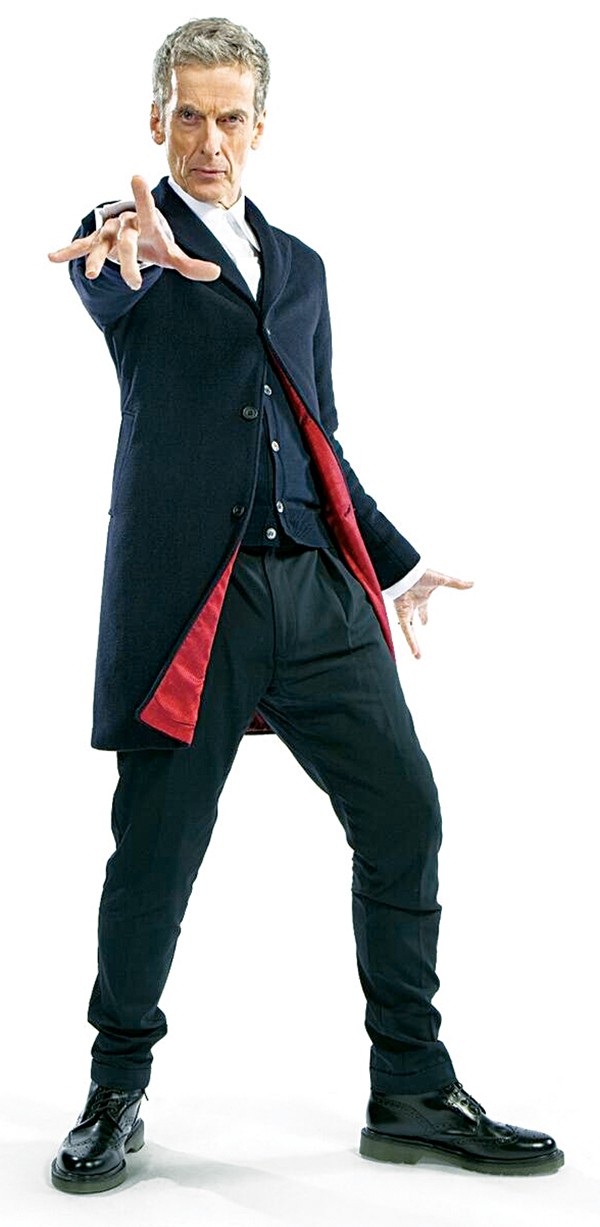

BBC.co.uk/doctorwho

BBC.co.uk/doctorwho

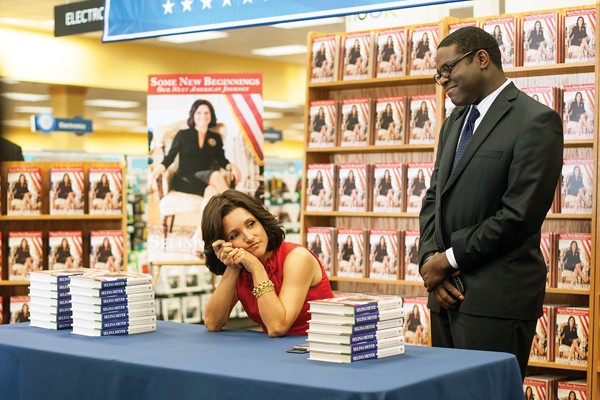

Paul Schiraldi

Paul Schiraldi