Patrick Lantrip

Patrick Lantrip

Denise LaSalle sing Carl Perkins’ song, “Blue Suede Shoes.”

On a chilly Saturday evening in Downtown Memphis, a diverse cross-section of locals congregated at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts to honor the achievements of an equally diverse selection of the city’s more euphonious residents. The tertiary edition of the Memphis Music Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony enshrined nine more members at the event hosted by actor and comedian Marlon Wayans. This year’s class included Carl Perkins, Ann Peebles, Big Star, Al Bell, Lil Hardin Armstrong, John Fry, Furry Lewis, Chips Moman, and Jesse Winchester, and was indicative of the heterogeneous hodgepodge of diverse styles that defines Memphis music.

Memphis Mayor A C Wharton was on hand to deliver a crowd-rousing commencement speech that began the night of performances, biographies, and genuinely touching acceptance speeches.

“This is what we’re all about, this is who we are,” Wharton said. “As the young folks say, this is the way we roll. We’re just full of soul.”

[jump]

However, it was Wayans and his impromptu rapport with announcer, Leon Griffin, whose voice Wayans repeatedly referred to as “Black God,” that set the tone of the event and provided a lighthearted counterbalance to some of the evenings more solemn moments. Wayans delivered a solid performance as MC, and playfully poked the crowd while cracking jokes about Memphis weather, its size, and Elvis’ late in life wardrobe.

The first inductee to be honored was Lil Hardin Armstrong, the wife of Louis Armstrong, who as an accomplished jazz singer in her own right. “Hot Miss Lil” made a name for herself up and down the Mississippi River in the 1920s before she met Armstrong, and she is cited as a major reason for his success. Joyce Cobb performed a tribute to Hardin that harkened back to the smoky Chicago nightclubs that launched Hardin’s career.

Next, soon-to-be inductee John Fry introduced power pop pioneers, Big Star. The band took their name from an eponymous, now defunct area supermarket, took their sound of the Beatles, The Who and The Byrds and made into something uniquely their own. As the last living original member, Jody Stephens performed with next-gen members Jon Auer and Ken Stringfellow, of Posies fame, after accepting his award. The trio was joined on stage by Drew Hummel, the son of original member Andy Hummel, and Steve Selvidge.

Selvidge stayed on stage to present the award for Walter “Furry” Lewis, a depression-era delta bluesman that also played a major role in the blues revival scene of the 1960s. Contemporary bluesman Ronnie Baker Brooks performed the musical tribute to Lewis.

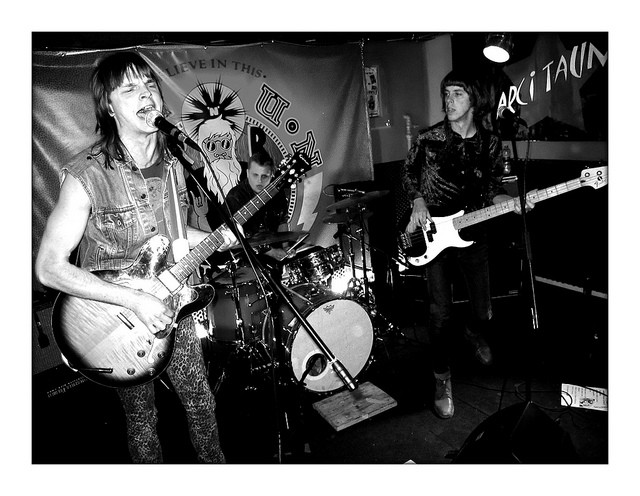

Dixie Fried Rockabilly virtuoso and Million Dollar Quartet member, Carl Perkins was honored next with a performance by “Queen of the Blues” Denise LaSalle, who was a close friend of Perkins. She also reminisced about a story Perkins told her about his most famous hit, “Blue Suede Shoes,” before performing the song much to the delight of the crowd.

Jesse Winchester may not be a household name in the States, partly due to the fact the he became a Canadian citizen to avoid the Vietnam War, but the CBHS graduate’s folk-style music influenced a number of artists, including six-time CMA Musician of the Year, Mac McAnally, who also performed his tribute. Sadly, Winchester passed away earlier this year, just one month after receiving an invitation to be inducted in the MMHoF. His family was on hand to accept the award on his behalf.

Owner and founder of the legendary Ardent Studios, John Fry was next. Stephens returned to present the award to his old friend and colleague, and then the quartet of Selvidge, Stringfellow, Auer, and Stephens returned to play another set.

For a musician there are few compliments that rank higher than being told by John Lennon that one of your songs is “the greatest ever written,” but for Ann Peebles that is just one feather in her cap. Her husband Don Bryant, who co-wrote “I Can’t Stand the Rain” with Peebles presented the award. Peebles, who spoke to the Flyer before ceremony, said that encounter was one of the highlights of her career.

“It was the very first time I traveled abroad,” Peebles said. We sat down and talked, and even he came to my show one time. It was one of the most exciting times in my career.”

Sam Moore of Sam and Dave fame performed a rousing version of “I Can’t Stand the Rain,” with some help from Peebles and Bryant in the audience, and Lawrence “Boo” Mitchell played the electric timbales that are responsible for iconic rain sound at the beginning of the track.

“I feel blessed to have all of my accomplishments recognized,” Peebles added.

Chips Moman was responsible for engineering the sound of many artists, but perhaps he is most famous for Elvis Presley’s revival, producing such hits as “In the Ghetto” and “Suspicious Minds.” Another one of his collaborators, B.J. Thomas of “Rain Drops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” fame accepted the award on behalf Moman, and performed a version of the Moman-produced hit “Hooked on a Feeling.”

The final act of the evening was in honor of former Stax owner and Motown executive, Al Bell. Bell was an integral part of the Stax sound that tore up the airwaves in the 1970s and was the mastermind behind the Wattstax Music Festival, and the subsequent Golden Globe Award winning documentary. William “Born Under a Bad Sign” Bell and Memphian, Al Kapone joined forces for an updated rendition of the Stax-era classic “I Forgot to be Your Lover.” For the finale, Bell remained on stage to perform an extended version of “Knock on Wood,” that brought the crowd to a standing ovation.

Patrick Lantrip

Patrick Lantrip