“In the upward progress of the human race certain spots favorable to its activities become the center of accounts more or less accurate, more or less mythical, of these primeval struggles. Such a spot is this.” — Dr. B.F. Turner at the dedication of the De Soto Memorial, May 1919

Just south of the Memphis-Arkansas Bridge, the bluff-top area in downtown Memphis that today includes Chickasaw Heritage Park and the National Ornamental Metal Museum has had many tenants over the centuries: Paleo-Indians left mounds here; it was a fortress of Chickasaw chief Chisca; it was the French Fort Assumption in the 1700s; the U.S. established Fort Adams and then Fort Pickering on the site just after 1800; it was a point of Southern consternation during the Civil War; a Marine Hospital was built there in 1884 and upgraded beginning in 1937; it was the entertainment district Jackson Mound Park for Memphians beginning in 1887; DeSoto Park was dedicated in 1919; a residential subdivision called French Fort has been there since the 1960s; the 330th Army Reserve hospital unit began treating soldiers there in the latter 20th century; and the National Ornamental Metal Museum opened its doors in 1979.

It’s the place that Memphis park commissioner Dr. B.F. Turner called the most historic spot on the Mississippi River (The Commercial Appeal, June 8, 1935). When Turner said that about the site, he was doing so partly according to the conventional wisdom of the time: that this was the location where Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto first saw the Mississippi River. Historians have since refuted that, but there’s no denying that there’s something about this spot that made it so important to so many people over so many centuries.

Now the area is preparing for its next act, and if developer Lauren Crews has his way, what’s next for the French Fort area will be worthy of its storied past. Crews’ DeSoto Project looks to keep the site connected to its history, reconnected to the downtown core, and developed with a new element of luxurious living that would have left soldiers barracked there under General Zachary “Old Rough and Ready” Taylor more than a little envious.

by Greg Taylor

by Greg Taylor

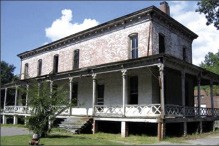

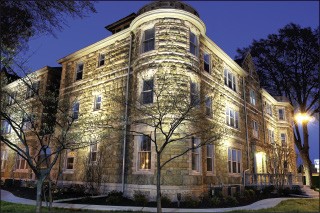

The nurses’ quarters and Marine Hospital are the focus of the DeSoto Project.

Crews purchased the old Marine Hospital, nurses’ quarters, and maintenance building — all sitting on 3.17 acres — about four years ago. His DeSoto Project vision is, in part, to turn the Marine Hospital buildings into an upscale condominium community. He plans on renovating each of the buildings, restoring them to their bygone glory. The developer, whose previous projects have included historic homes and grocery stores, says, laughing, “It’s another restoration. It just happens to be 10 times bigger. It’s a very unique place. There’s nothing like it in the world.”

The main Marine Hospital building was built in 1937 under an act of the Works Progress Administration. (The original Marine Hospital was torn down to make way for the upgrade.) The Georgian-style building has slate roofing, a copper cupola on pedestals, and large limestone columns, capitals, and gutters. Crews calls the workmanship and materials “the best imaginable during that era and all eras.” It’s no surprise that the sturdy federal building doubled as a fall-out shelter. Visitors touring the abandoned hospital may feel a slight chill induced by watching too many late-night horror movies, but as Crews insists, “There are no ghosts in the place. You can slip up on a scary cat, though.”

by Lauren Crews

by Lauren Crews

The nurses’ quarters was built in 1878 and moved a hundred feet in the 1930s when the new Marine Hospital was built. It’s brick with metal roofing and a wrap-around porch with columns and other woodwork. Its walls are about 13 inches thick. The two-story brick maintenance building was erected in 1940 and has high ceilings and cypress windows on the front.

Crews’ DeSoto Project envisions 45 units all told, each of them 2,000-plus square feet. Broken down, it looks like this: phase one with 29 units in the three-floor Marine Hospital and three units in the nurses’ quarters; and phase two with six units in the maintenance building and seven more in a new construction. Prices are tentatively ranged from $320,000 to right under $700,000.

The grounds will be landscaped with an “elegant” pool, a New Orleans-style courtyard, and other amenities. One bonus for Crews: the mature trees that cover the grounds. Another: The Mississippi River is 800 feet away. Twelve units will have true views of the river. According to Crews, “With its historic integrity, under a canopy of trees, surrounded by parks, on the river bluff, overlooking the river, one mile from Tom Lee Park, and the arts with the Metal Museum in the backyard, it has the makings of a great place.”

by Greg Taylor

by Greg Taylor

With Wall Street giving investors a case of whiplash and the downtown Memphis condo market sluggish, one may fairly wonder, why now? “People may think this is not the best of times to be thinking about doing a development,” Crews says. “But I think it is the best of times. I admit I’m in the minority.”

Crews points out that, for starters, the DeSoto Project is relatively inexpensive to start up. He plans on building a model unit in the Marine Hospital, which will have the rare benefit of being a unit in the actual building that prospective buyers can experience rather than just visualize. Pre-sales will be made off of the model before the main thrust of construction begins. “We’re going to keep our investment to a minimum until we have the pre-sales,” Crews says.

He also points to the perpetual cycle of real estate product glut followed by scarcity in the market. Though there’s a glut right now, what about in several years when the DeSoto Project would come online? Commodities markets such as raw construction materials and oil are down right now, too — they’ll be back up after the economy rebounds, so it’s cheaper to take advantage of building on the front end of the curve.

The bottom line for Crews is the unique property itself: “I also point out that I might not feel exactly the same way if I was talking about your typical condo project in the downtown area.”

Crews also owns an old motel around the corner from the Marine Hospital, right at the gateway to Memphis as drivers come over the Memphis-Arkansas Bridge. He’s planning an adaptive reuse of the property, but it’s too soon to say what that will be.

One of the main developments in this unfolding story will be which plan the Tennessee Department of Transportation chooses in redesigning the fly-by exchange between Crump, Riverside Drive, and I-55. Which way TDOT jumps will go a long way toward what will happen to the motel property and the French Fort area in general. Crews says, “For the community, we need to do what we can to reconnect this area back to the downtown core rather than do something that further disconnects it.”

On the whole, it’s an effort that Crews compares to the famed revitalization of the Pearl District in Portland, Oregon. “I see in the area urban revitalization at its very best,” Crews says. “I see roads that are three times as wide as they need to be — we can add median strips. I see parks that are totally underutilized. I see an area that is disconnected from the downtown core, with the potential for reconnecting with the River Walk, with sidewalks, with alternate transportation potentially, and changes in the road system.

“I see a bigger picture. But first things first, and that is the development of the Marine Hospital property. I see that as the catalyst for other development.” ■

by Terry Woodard

by Terry Woodard  by Terry Woodard

by Terry Woodard  by Terry Woodard

by Terry Woodard  Courtesy of Blackstar Capital Partners

Courtesy of Blackstar Capital Partners

Courtesy Crye-Leike Realtors

Courtesy Crye-Leike Realtors