Football is a sport designed with lengthy delays, typically six days off for every game day. Basketball is very different, a sport built around rhythm and flow. Ask a hot shooter when he’d like to have a day off and he’ll say when the season’s over. When the Memphis Tigers next take the floor (Wednesday night?), they will have gone almost three weeks (at least) without playing a game that counts. With a 12-6 record (and only three losses in American Athletic Conference competition), Memphis is, by the numbers, in contention to win a league championship and earn an NCAA tournament berth. But what kind of Memphis team will we see after such a lengthy interruption by Covid-19?

Joe Murphy / Memphis Athletics

Joe Murphy / Memphis Athletics

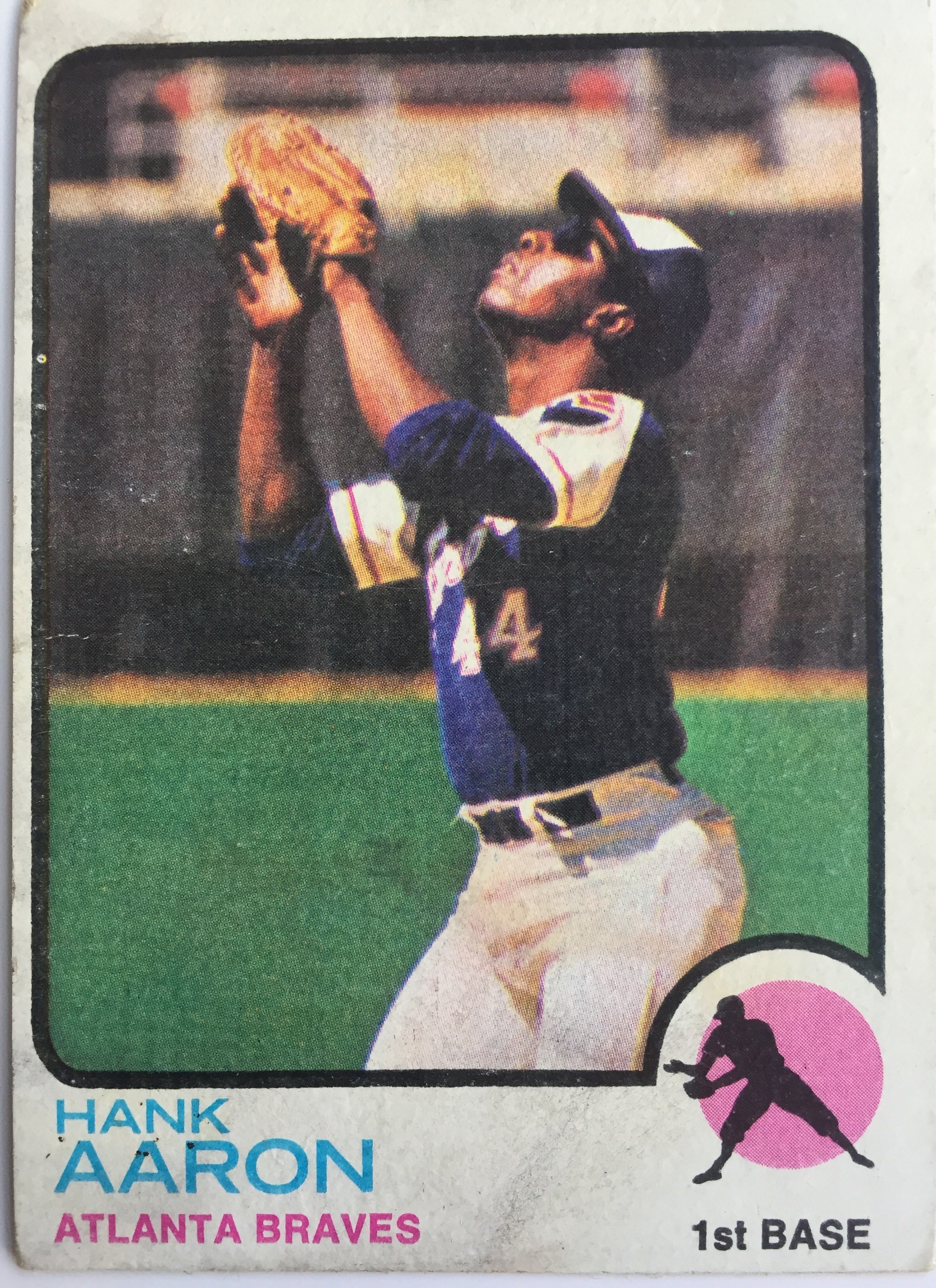

Alex Lomax

The Tigers won six of their last seven games before the current lockdown, thanks largely to collective shooting improvement. Over one five-game stretch, Memphis shot 49 percent from three-point range and moved to the top of the AAC in the category. Will Landers Nolley, Lester Quinones, and friends be on target when the season resumes?

Alex Lomax was playing the best basketball of his three-year college career before the lockdown. The pride of East High did his best Antonio Anderson impression in the Tigers’ last game, a win over East Carolina: 10 points, 9 assists, 5 rebounds, 5 steals. Will Lomax be a difference-maker when the Tigers return to play?

The AAC tournament is scheduled for March 11th-14th in Fort Worth. That’s less than three weeks. With four games remaining on the Tiger schedule, how many of the four games postponed this month (so far) can be played? Among those games: two against Houston and one against Wichita State, the teams Memphis must leap to win the conference title. (One of the Houston games and the Shockers contest are among the postponements.) And if the Tigers only complete a partial schedule, what will that mean for seeding at the AAC tourney? What will it mean for at-large consideration for the NCAA tournament? We’re still living in a pandemic. There are more questions than answers, naturally.

• A distinct ray of sunshine during last week’s historic deep freeze was the Memphis Redbirds’ 2021 schedule release. Even the idea of a baseball game at AutoZone Park — Opening Day April 6th! — feels like a shortening not only of winter, but the pandemic (which cost the Redbirds their entire 2020 season). The Pacific Coast League is a thing of the past. Memphis will now compete in the Triple-A Southeast Division. Instead of traveling as far as Tacoma, Reno, and Albuquerque to play, the Redbirds will compete with teams from Louisville, Jacksonville, and Gwinnett (the Atlanta Braves’ Triple-A affiliate), cities we can call regional rivals, at least with a wink.

Those into pop culture will welcome visits to AutoZone Park by the Durham Bulls (for whom Crash Davis starred) and Toledo Mud Hens (adored by Corporal Klinger from MASH). There was a time when Memphis-Louisville was Ali-Frazier in college basketball. Now, the Redbirds will play several games against the city the franchise called home before moving to Memphis in 1998. And hey, Bats and Redbirds are natural enemies, aren’t they?

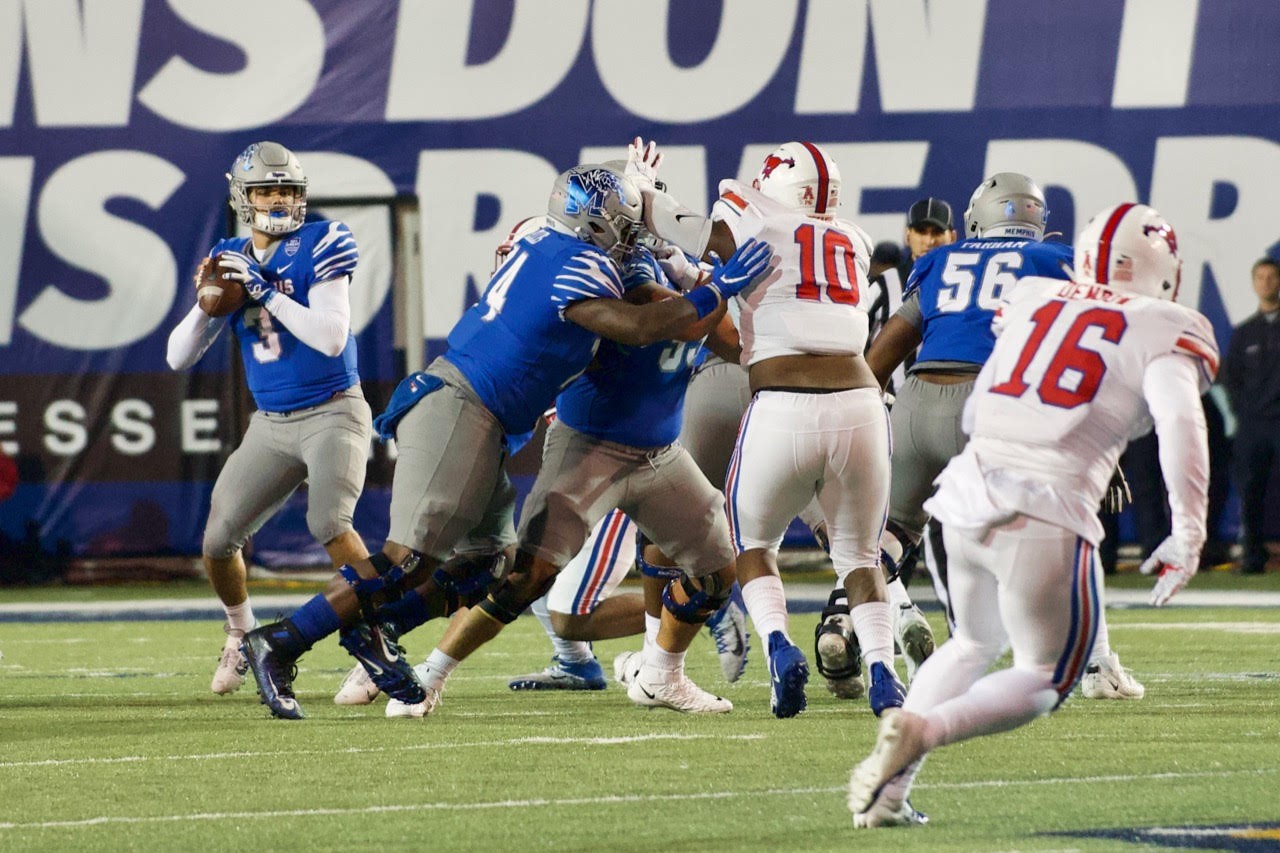

• The Memphis Tigers last played Mississippi State on the gridiron in 2011. Justin Fuente’s name was not on the minds of Tiger fans ten years ago, much less Mike Norvell’s. It’s been two legitimate “eras” since the Bullies came to town. The drought ends September 18th. The Tigers will likely carry a 16-game home winning streak into the showdown with SEC competition. (Memphis opens its season two weeks earlier by hosting Nicholls State.) Let’s hope, here in February — still winter, still pandemic conditions — that the Tigers and Bulldogs clash in a packed Liberty Bowl. In many ways, that would be a larger victory than anything Memphis fans might see on the scoreboard.

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski  Jj Gouin/Dreamstime

Jj Gouin/Dreamstime  Jj Gouin/Dreamstime

Jj Gouin/Dreamstime

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski  Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski  PGA TOUR

PGA TOUR