The athletic department at Lane College had an idea. They knew East High School, coached by Lane alum and former basketball player Desmond Merriweather, would be in Jackson, Tennessee, on December 19 to face a local high school, Liberty Tech Magnet. It would be the perfect time to honor Merriweather for his contributions while at the college. They wanted to surprise him with a special ceremony during the game.

The Lane basketball team showed up to meet Merriweather, the man they had heard so much about, as did the college’s president, Logan Hampton. But Merriweather wasn’t there. His absence was an excused one, however, as the East coach continues his five-year battle with colon cancer. His son, East point guard, Nick Merriweather, accepted a retired jersey, a basketball signed by the team, and framed stats on behalf of his father.

“It really brought tears to my eyes,” said Merriweather. “My son got the opportunity to see the things that I did playing basketball.”

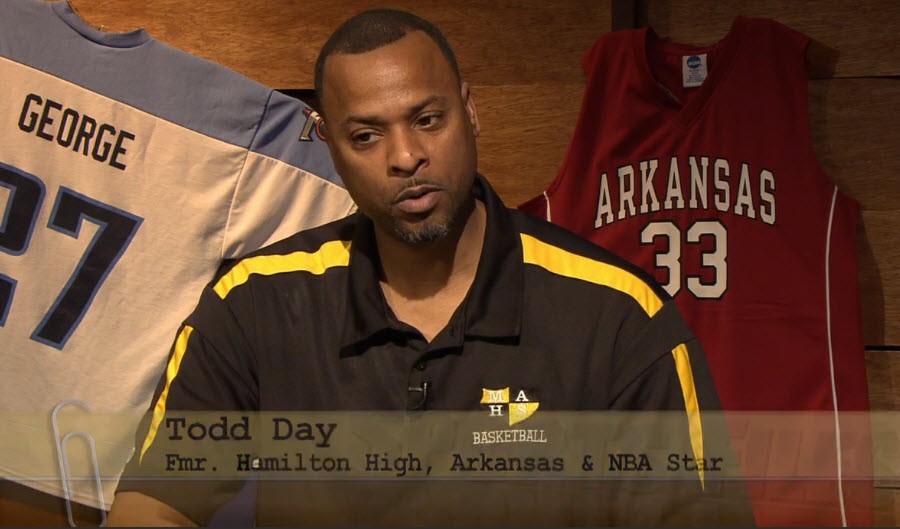

Like several of his East Mustangs teammates, Nick was coached by Merriweather at Lester Middle School. It was at Lester that Merriweather found out he had cancer. When he learned he would be spending a lot of time receiving treatment for the disease, he essentially surrendered control of the Lions to childhood friend and former NBA star, Anfernee ‘Penny’ Hardaway.

The East players understand they may be without Merriweather at times, but unlike middle school, Hardaway is not there to fill the void. Hardaway does offer scouting reports to the East coaching staff, but Merriweather’s primary assistant now is Robert Jackson.

Jackson prepped at East, graduating in 2004. Merriweather’s brother Marty was Jackson’s middle school coach. When Merriweather landed the coaching job at East, he called on Jackson, who was teaching alegbra at the school. Jackson initially assumed he would be just checking on the players and making sure they were attending classes. But soon he was asked to serve as Merriweather’s top assistant — and head coach by default when Merriweather’s health demanded it.

“It’s been an adjustment,” says Jackson. “I’ve been operating in a different role for them. My biggest challenge is getting them to respond to me the way they respond to Coach Dez.”

Earlier in the season, with Merriweather’s status uncertain, Jackson was at the helm for East’s game at Houston High. He was disappointed with the way East was playing.”We had a 6-point lead,” Jackson says. “But we were playing really sluggish.”

Then Merriweather appeared early in the second quarter and resumed his coaching duties. “You could tell they were playing for him,” says Jackson. “That six-point-lead ballooned to 18 points in no time.” East won by 20.

Jackson knows he’s slowly getting through to them, but understands it will take time. And there’s never been any conflict between Merriweather and Jackson; when Merriweather is available, he’s the coach. “He’s a legend in Binghampton,” Jackson says. “He is Binghampton.”

Two days after missing the ceremony in his honor in Jackson, Merriweather’s family held an early Christmas dinner to honor him at an uncle’s home in Midtown. A banner in the living room is filled with well wishes from family, friends, and his East High family. Merriweather is late, but finally arrives around 4 o’clock, weakened by his latest chemo treatment. He’s assisted out of the passenger seat and into his wheelchair. He doesn’t have the strength to roll it himself, and has to be pushed. Jackson makes his presence known to his mentor and talks with him briefly. Then leaves, taking what’s left of the sun with him. It’s as if the moment represents their coaching relationship. Jackson is there, ready when needed, yet it’s Merriweather who is the center of attention.

A few years ago, after undergoing a treatment, Merriweather left his hospital to visit another one. He was there to lift the spirits of his former East High School coach, Reginald Mosby, who is also battling cancer.

“He had just come out of the hospital,” Mosby recalls. “He was kind of half dragging when he came in, walking real slow. Of all of my people, of all my guys, he was the last one I expected to see. And I said ‘God is good.’”

“Everything I do when it comes to basketball is in honor of Coach Mosby,” Merriweather says. Which is why he decided to honor Mosby over the summer at Binghampton’s version of city hall — Lester Community Center. Several former East players and coaches came out to help.

Merriweather had planned to make Mosby the honorary coach of the team during East’s November 22nd, game against Memphis Academy of Health Sciences. But Mosby was under the weather and couldn’t make it. Still, for Merriweather, being in a wheel chair is just a temporary state that Mosby and basketball helped prepare him to deal with. “You go through things every day,” says Merriweather. “You have to take it for what it’s worth. You have different injuries playing basketball. Joints knocked out of place. I had a great coach in Coach Mosby, who prepared me for this situation.”

You can follow Jamie Griffin on twitter @flyerpreps.

WKNO

WKNO