In February 2006, nearly six months after Hurricane Katrina cut a 200-mile gash across Mississippi, the Magnolia State still looked like a war zone.  Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Before

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Today

More than 65,000 houses had been destroyed, and the damage estimates had climbed to $125 billion. In Biloxi alone, three out of four homes sustained damage, and of those, nearly half were considered irreparable. Demolished neighborhoods were strewn with muddy toys. Furniture hung from trees like surreal fruit. Cars were still in ditches, piled on top of one another. The mangled skeletons of fast-food joints and gas stations decorated the beachfront. To anyone who hadn’t witnessed the digging-out process firsthand, it looked like Katrina might have hit the day before. Everyone I interviewed on that trip, from Biloxi mayor A.J. Holloway to the man on the street, expressed the same sentiment: Things are really bad right now, but there will be visible progress in the next six months. Some, like Holloway, were generally optimistic; others just seemed to need hope in order to press on in their unrelentingly primitive circumstances.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

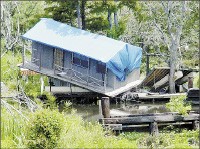

Six months later, the Gulf Coast is showing some signs of improvement, although it would be a stretch to say that things appear to be much better. Tons of rubble have been carted away, but the area still looks like a war zone. Neighborhoods reduced to splinters by Katrina have been converted into sprawling trailer parks with temporary porches and plumbing. Communities where the damage was severe but not terminal remain as empty as an Old West ghost town, with gaping holes in the walls and ceilings of every home. In some areas, the rumble of earth-moving vehicles blends with the sounds of busy saws and hammers, but it seems like the exception rather than the rule. Little, red “For Sale” signs dominate the landscape.

On Thursday, August 31st, the sumptuous Beau Rivage casino reopened on the beach in Biloxi, creating nearly 4,000 new jobs and an atmosphere of renewed hope. Casino employees paraded through the street in front of dignitaries such as Senator Trent Lott and Holloway. Mississippi governor Haley Barbour hailed the event as a “milestone in the recovery of the coast.”

“[The casino opening] underscores an important message that Mississippi is again open for business,” Barbour said. “The private sector will determine the success of our efforts to build a Mississippi that is bigger and better than ever.”

Even with commercial growth and the steady rebirth of the Gulf’s tourist industry, unemployment throughout the region ranges from 10 to 15 percent.  Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Today

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Before

In spite of the obvious need for jobs, many businesses in Biloxi, Bay St. Louis, Pass Christian, and Waveland are unable to keep regular hours due to a lack of manpower, and “Help Wanted” signs are almost as common as the ones reading “For Sale.” Business owners, according to reports in the Biloxi Sun Herald, blame the situation on the area’s lack of housing.

Property values have soared as homeowners, frustrated by their inability to get insurance companies to pay a fair price for damage incurred and daunted by new building codes and inflated insurance premiums, are hoping to sell their land to casino and condo developers. This, along with the federal government’s failure to produce funding beyond an initial $7 million HUD emergency grant, has further hindered the development of affordable middle-class housing. Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Before

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Today

The Gulf Coast may be less cluttered than it was six months ago, but the damage is no less shocking. And while there is no doubt that many aspects of Mississippi’s tourist industry are bouncing back, the human disaster can still be easily measured in the number of tents, trailers, and ruins that dominate the landscape. Mississippi may be “open for business,” but beyond the beautifully appointed casinos, it’s understaffed and keeps irregular hours. Reservations are advised.  Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Before

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Today

Although much of the rubble has been removed and

temporary fences have been erected, vast portions of the

Mississippi Gulf Coast are still in ruins.

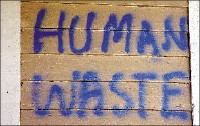

Bay St. Louis’ historic downtown was wrecked by Katrina. Many buildings not demolished by wind and rain were made uninhabitable by human waste and black mold. The road separating downtown from the beachfront had been completely erased but is slowly being reconstructed. Some buildings that seemed unsalvageable are being rehabilitated, but much of the town still looks the same as it did six months ago. Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Before

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Today

It’s difficult to measure the devastation in places like Waveland, where many neighborhoods were completely blown away. Many former residents have hung flags and signs to speak for them in their absence. Lower photos: In February, the Biloxi Community Center housed FEMA and a not-for-profit group called Midwest Help. It was also a relief station for National Guardsmen. Midwest Help was evicted in late February and FEMA has moved. On September 2, 2006, the building was open and empty.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Today

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Before

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Before

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Before

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Today

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Today