Could there be a more fiendishly designed story than Confederate parks and General Nathan Bedford Forrest to insure that Memphis forever trips over its own feet (well, maybe the Ford family saga)?

As City Councilman Lee Harris said, “It’s done” as far as renaming the parks. But it’s not over. This story has legs, as we say in the news biz. It also has horses, troops, and a cavalry. There are editorial revisions yet to come for the generic placeholder names, assuming a panel can be assembled that will agree on anything. But the real secret to the longevity of this story is no secret at all. It embraces the themes of race that Memphis loves so well.

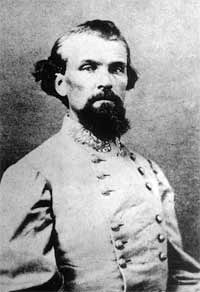

If Forrest were alive today he would be coaching football at the University of Alabama. He would have figured out a way to beat Texas A&M, and he would be the darling of ESPN and the bane of reporters if he could not have them all flogged. As my colleague Chris Herrington says, a lot of people ignore the cause and confuse “war hero” with “great general”. Forrest is a war hero to unreconstructed white southerners like the ones writer Tony Horwitz described in his book “Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War.” He is an annoyance or worse to black Memphians for his ties to Fort Pillow and the Ku Klux Klan.

Shelby Foote, the great Memphis Civil War historian and author, wrote a lot about Forrest in Part Three of his trilogy. Forrest, who was in overall command at Fort Pillow, “was widely accused of having committed the atrocity of the war. ‘The Fort Pillow Massacre,’ it was called, then and thereafter, in the North.” Foote wrote that, in fact, Forrest “had done and was doing all he could to end it, having ordered the firing stopped as soon as he saw his troopers swarm into the fort, even though its flag was still flying and a good part of the garrison was still trying to get away.”

Foote died in 2005, shortly before the last (as in last one before this one) Forrest fight was staged. He opposed renaming Forrest Park as well as Confederate Park and Jefferson Davis Park. The statue of Jefferson Davis in Confederate Park (yes) was placed there in 1964 during the heat of the civil rights era and desegregation, the year after Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington and the year three civil rights workers were murdered in Neshoba County, Mississippi. It is impossible to imagine that its backers were not aware of the context. The Davis statue is more a political statement of those times than a monument to the Civil War. Davis could be in greater danger than Forrest.

If Nathan Bedford Forrest Park was on a less prominent street than Union Avenue, or if the general’s grave had not been moved in 1905 from Elmwood Cemetery where he was originally buried, the general would not get so much attention. But the park, with its equestrian statue of Forrest, is in the heart of the downtown medical center shared by the University of Tennessee and Baptist and Methodist hospitals that is finally showing renewed signs of life and investment. The Forrest grave site is a perfect spot for his admirers, whatever their motives, to put a thumb in the eye of the general’s critics, especially if they happen to be black.

Moving the monument and the graves of Forrest and his wife back to Elmwood, as some have suggested, would be one of the great media events of our time. Reenactors in full uniform would line the streets every foot of the way. Counter-demonstrators would turn out in equal or greater numbers. And every national news report would herald “Memphis Relives The Civil War.”

The City Council will revisit the issue soon. Councilman Myron Lowery has suggested adding a statue of Ida B. Wells to the park, a sort of one-of-ours-and-one-of-yours compromise. The problem with that is that some Memphians may not wish to identify with either one. If you are white, was Forrest “ours”? He belongs to history. His monument and grave have been there for 108 years. Moving them would make the annual Shiloh reenactment in April look like a church picnic. Union Avenue between Manassas and Cleveland is prime real estate that, hopefully, will one day look more like a medical center on the order of Nashville or Jackson, Mississippi. It’s complicated, fiendishly complicated. And not over by a long shot.