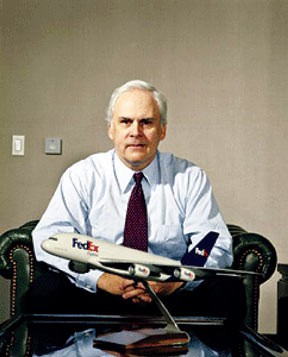

FedEx founder and CEO Fred Smith, a master of the marketplace and job creation, has added his support to the consolidation effort, a war of words that will be decided at the ballot box.

“The fundamental problem in Memphis and Shelby County is we are simply not competitive in terms of the cost of our government structure, and we are losing population, and we are not growing as fast as our peer competitors,” Smith said in an interview with the Flyer. “Unfortunately, in a market-based economy, not to grow means that your standard of living is going to decline. It’s just that simple. We are not competitive.”

Smith did not join other business leaders in a pro-consolidation rally last month, because FedEx generally does not take positions on local political matters, but his personal support is no surprise. Four generations of his family live in Memphis. His son, Richard Smith, served on the Metro Charter Commission that drafted the consolidation proposal, and former FedEx senior attorney Julie Ellis was chairman of the commission. Fred Smith is a lifelong Memphian and the greatest job creator in the history of the Memphis area, where FedEx employs more than 30,000 people.

In the interview, Smith referred several times to Nashville and Indianapolis as peer cities with more efficient and less expensive governments than Memphis due to consolidation. He said Nashville/Davidson County provides essentially the same services as Memphis and Shelby County for roughly $350 million a year, or $1 million a day, less money than Memphis. Nashville consolidated by referendum in 1962 and Indianapolis by state legislative action in 1970.

“I think the best figures I saw over the last 10 years, relative to Nashville, we have had $3 billion less economic activity,” he said. “Part of the reason is they have more efficient government. Nashville used to be a smaller city than Memphis. Now it’s bigger than Memphis. We have, as I understand it, about 14,000 people in our combined government structure, and Nashville has 7,000 and something. That’s a striking difference.”

The property tax rate in Memphis is $7.27; in Nashville the urban services rate is $4.13. According to a spokesman for Nashville mayor Karl Dean, Nashville has 10,694 general government employees. Nashville’s consolidated school system has approximately 70,000 students, or about half as many as Memphis City Schools and Shelby County Schools combined. The school systems would remain separate under the proposed metro charter.

Smith and FedEx are very familiar with Indianapolis.

“We have a huge hub there, a huge hub,” he said. “I have to tell you, it’s a very easy proposition to deal with them. When Mayor [Stephen] Goldsmith was up there, it was a delight to work with those people. Our Memphis airport is as efficient as anybody in the world, and we deal with Hong Kong and Paris and everyone in between, but in Indianapolis, to expand our hub actually required the rerouting of one of the highway systems, and it was just so easy to deal with them.”

Goldsmith, who was mayor of Indianapolis from 1992 to 2000, is a consultant to the Metro Charter Commission and Rebuild Government.

The consolidation referendum on November 2nd must pass separately in the city of Memphis and in Shelby County outside of Memphis. Early voting starts on October 13th. Smith praised the draftsmanship of the charter commission, which spent several months holding public hearings and working on the document. But he acknowledged, with a laugh, that it is not likely to pass. Suburban mayors are unanimously opposed to it, as is Shelby County mayor Mark Luttrell.

“It actually enhances the political situation for the county and is a pretty balanced document,” Smith said. “I was surprised at how well they did in trying to meet the needs of the various constituents, but it doesn’t look like it’s done any good.”

A poll by Yacoubian Research in September showed that 72 percent of county voters oppose consolidation. Berje Yacoubian said endorsements could have some impact but not much.

“The average county voter doesn’t care if Fred Smith or Pitt Hyde are for it,” he said. “They are going to oppose it if they think it hurts them in the pocketbook.”

Smith acknowledged that proponents of consolidation must sell it without any special authority or a command structure. The war of words over the 48-page proposed charter is being waged in public meetings, on editorial pages, via anonymous comments in the blogosphere, and in television sound bites.

“It’s very tough, and from what little I have seen about it, there is an enormous amount of misinformation out there, probably deliberately,” Smith said.

I asked Smith if failure of the consolidation referendum would influence FedEx’s thinking down the road. Even if consolidation were to pass, it would not be implemented until 2014.

“We will have to wait and see,” he said. “One of the things that concerns us a lot as a very large taxpayer is the redundant expenses and the loss of the population base due to out-migration. We think that the government leaders have to basically accomplish what the charter commission is trying to accomplish. If the voters don’t want to consolidate the governments, they have to consolidate the functions to get to the same economic costs. I think that would be Plan B. Mayor Wharton and Mayor Luttrell have to get together and say, ‘We cannot run this community with a noncompetitive cost structure.'”

Smith said two-headed government has hindered economic development because “we cannot speak with a single voice.” He cited the lengthy process of getting Bass Pro to take over the Pyramid as one example. But he said the lack of consolidated government was not to blame for the fact that in the 1990s Memphis did not get an NFL franchise when Nashville and Jacksonville did. Unlike the Bass Pro deal, Smith was personally involved in that effort as one of the would-be owners.

“We [Memphis] just wouldn’t build a new stadium,” he said. “The NFL told us point blank: no new stadium, no franchise. So Jacksonville got our franchise. I wouldn’t say consolidation was the biggest factor.”

FedEx recruits more outsiders to its Memphis world headquarters, airport operations, logistics division, and executive offices than anyone in town.

“I think our experience is that people are generally negative on Memphis initially and pleasantly surprised when they get here,” he said. “Particularly about the cost of housing and the lack of traffic congestion. Generally, though, if they come here, it is because they really want to work for FedEx.”

On his own plans for retirement, Smith, 66, repeated what he recently said at a meeting with business reporters and analysts: “I’m not going anyplace for a year, and I doubt it would be three years,” he said. “But in five years, probably … I would be 71, and this is a job that requires your full attention. But I’m enjoying it. I’m not doing anything in the near term.”

It is easy for Memphis to take FedEx for granted. The Super Hub isn’t going anywhere, and FedEx is tied to some new offices and big pieces of real estate in East Memphis, Southwind, and Collierville. But FedEx has hubs and big investments in Indianapolis, North Carolina, Alaska, Colorado, Brussels, Beijing, Paris, and a lot of other places too. Maybe five years from now, and certainly 10 years from now, Fred Smith won’t be running FedEx.

Holiday Inns used to be tied to a big piece of real estate on Lamar Avenue. Schering-Plough was tied to Jackson Avenue. And the cotton business was synonymous with Front Street. But cotton is a downtown museum today. Kemmons Wilson died. Abe Plough died. And pretty soon the companies they founded went away.

It’s the nature of business. It’s a big world. And Memphis is not competitive.