JB

JB

Despite numerous witnesses protesting the action, the Council voted 11-1 to remove Forrest statue.

On Monday came, as expected, the City Council’s approval, on the third and final reading, of an ordinance “to transfer ownership of the equestrian statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest and to remove and relocate said statue from the City of Memphis’ Health Sciences Park.”

And tucked into the ordinance, as a sort of tardy, even anti-climactic, after-thought, was a clause ratifying the Council’s decision of February 3, 2013, to rename said park along with two other downtown parks, Memphis Park, formerly Confederate Park, and Mississippi River Park, formerly Jefferson Davis Park.

The latter clause was designated “Nunc Pro Tunc,” legalistic Latin phrase meaning, literally, “now for then,” making the renaming retroactive to the 2013 date.

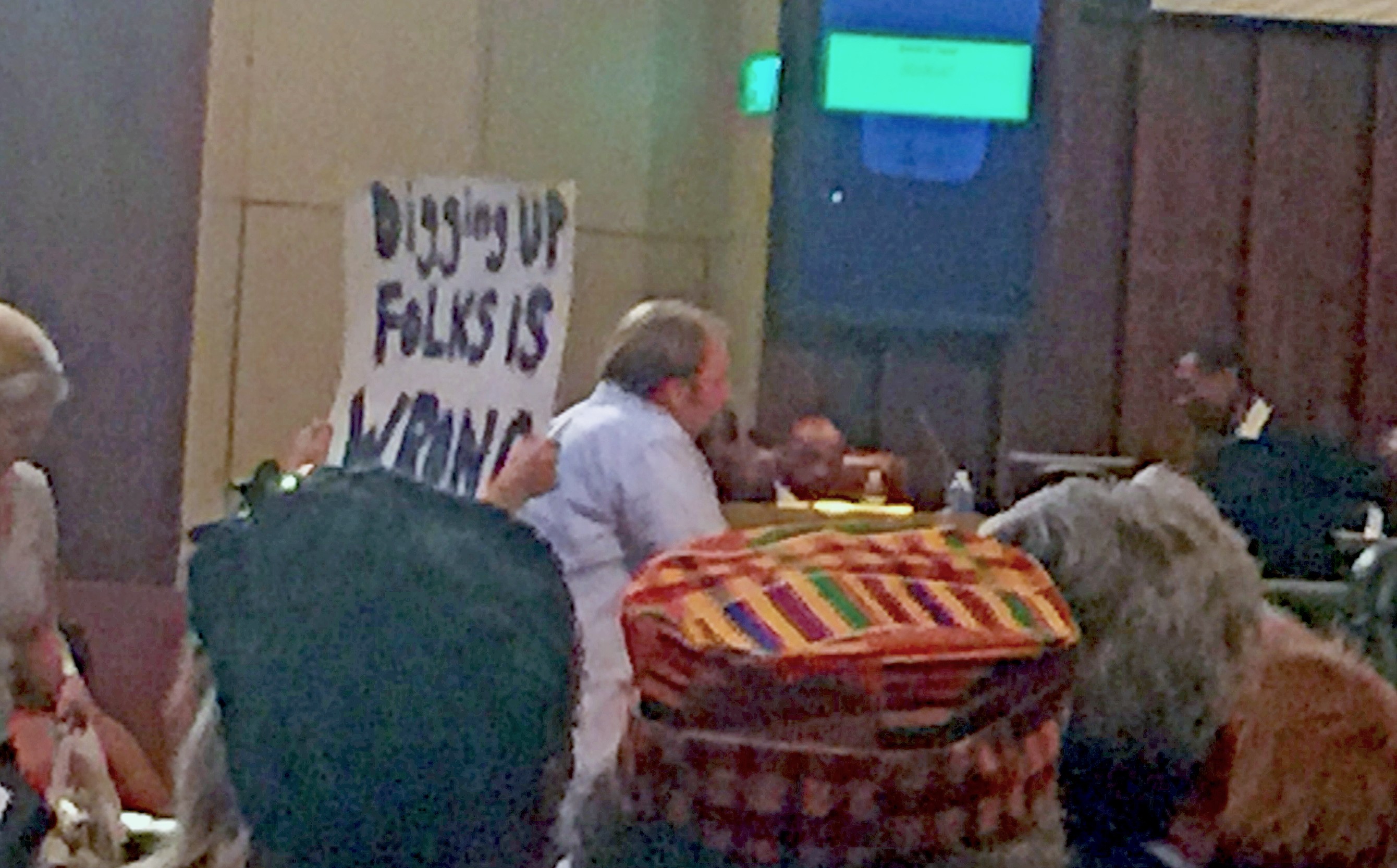

The number of people willing to speak to the Council in favor of General Forrest or, in one case, on behalf of his wife Mary, or against the ordinance was larger by far than it had been back in July when the ordinance was first proposed, and their testimonies ran the gamut from closely reasoned and historical to emotional and personal.

They also had on their side a convert of sorts: Bill Boyd, chairman of the Council’s parks and neighborhoods committee, which had charge of the ordinance.

Boyd, who had voted aye along with the rest of the Council on first reading of the ordinance, demurred this time and balked at introducing the ordinance until Council chairman Myron Lowery reminded him that his action in doing so would not confer his approval but would merely call the measure up for discussion.

In the end, the ordinance would pass 11-1, Boyd casting the only nay vote, though Edmund Ford Jr. was recorded as present but not voting.

There was no debate as such from members of the Council, and, for all the occasional passion of audience testimony, both pro and con, there were but two minimal breaches of decorum.

One came when the Council attorney Allan Wade was asked to cite the legal basis for the Council’s action and, as he was searching among his papers for the relevant text, witness Lee Millar of the Sons of Confederate Veterans stood and began to approach Wade with an apparent counter-argument. (An onlooker suggests that Millar was merely offering to assist Wade with a recalcitrant microphone.) “You need to sit down,” Wade said sharply, and Millar withdrew.

Another moment came after the vote when the sizeable audience contingent that had opposed the ordinance rose and began to file out of the Council auditorium. One member of the group began to loudly sing a chorus of Dixie. “Okay, they’re going to be rude on their way out,” chairman Lowery was heard to say. But the songster subsided when no other voices joined in.

But in general the resisters, though clearly disappointed, were orderly, and, after all, they knew, as members of the Council did, that, while one phase of things was concluded on Monday, the battle was far from over.

It remains moot whether, and to what degree, action to remove the statue can be retarded under a state law against removal of war memorials hurried onto the books by the legislature in 2013, at the time of the first Council actions to transform the nature of what was then still Forrest Park.

And, though much of the audience testimony on Monday questioned the propriety of removing the bodies of General Forrest and his wife, that point was not addressed by the Council ordinance.

The Council had passed a resolution in July to return the bodies to the Forrest plot in Elmwood Cemetery from whence they were transferred to the downtown park designated in the general’s honor in 1905. The Forrest family has not conferred its approval on the action, which will be litigated at some point in Chancery Court.