JB

JB

The GOP’s Chism hurls a barb as Democrat Melvin Burgess looks on in apparent approval.

The administration of Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell had, over the last month, fought — and won — a skillful battle with Commissioners of the Mayor’s own Republican Party over the fiscal 2015-16 budget and tax rate.

The Mayor’s preferred $4.37 tax rate was up for a third reading in budget committee Monday — unchanged from this year and lacking the one-cent tax decrease the GOP contingent had, in previous meetings, tried hard to squeeze out of Luttrell’s well-advertised $6 million surplus.

The tax rate sailed through committee this time out, and there were no new objections to the Mayor’s proposed $1.1 billion budget. Instead of the usual stack of stapled-together sheets, Monday’s agenda was confined to a single scanty sheet, so — Done deal, and the war’s over, right?

Wrong.

The final two items of Monday’s committee agenda looked innocent enough on paper.

One was a “discussion” of the administration’s decision to end a 30-year relationship with Nationwide Insurance as handler of county employees’ alternate deferred-compensation retirement plan and to sign a new contract with the rival Prudential company. The other was a resolution by Democratic Commissioner Van Turner authorizing the Commission to hire its own attorney, a la the Memphis City Council, to deal with unspecified special issues.

The two proposals together ate up four hours’ worth of heated discussion, including a lengthy back-door executive session in which the argument was closed to the press.

And this time, unlike the case of the budget/tax rate conflict, the renewed battle saw the entire body of Commissioners present, Democrats as well as Republicans, arrayed against the Mayor. It was an eyeball-to-eyeball power struggle, pure and simple, and, though both sides gave a little, at the end it was the Mayor’s reps who may have blinked.

The matter of a revised contract with Prudential for the county’s 457 plan (as the deferred-compensation, defined-contribution plan is called in official jargon) had been raised by county CAO Harvey Kennedy at last Monday’s regular business session of the Commission, and there had been flak from several Commissioners, who expressed a preference for Nationwide.

But the 457 issue was lost in the shuffle of disagreement and maneuvering over tax-rate/budgetary matters, and things seemed placid enough on Wednesday morning when, at what seemed the tag end of the committee day, an administration review team sat at the witness table and laid out for the Commission’s general government committee a sequence of reasons for changing vendors, including a modest annual savings of some $60,000 in the Prudential plan.

Cascade of objections to new Prudential contract

If Luttrell, Kennedy et al. expected that to be that, their expectations were quickly dashed.

One by one, and regardless of party or their prior positions on the tax-rate-budget matters, the Commissioners present proceeded to question both the administration’s judgment on the 457 matter and its prerogatives.

Nationwide had been a good manager of the 457 plan and a generous ally with county government in various public-private partnerships providing recreational and other services to constituents, GOP member George Chism objected.

The new contract’s provision of office space for Prudential in the Vasco Smith County Administration, a prerogative never offered to Nationwide, invited a “cozy relationship” that was improper, the GOP’s Heidi Shafer objected.

JB

JB

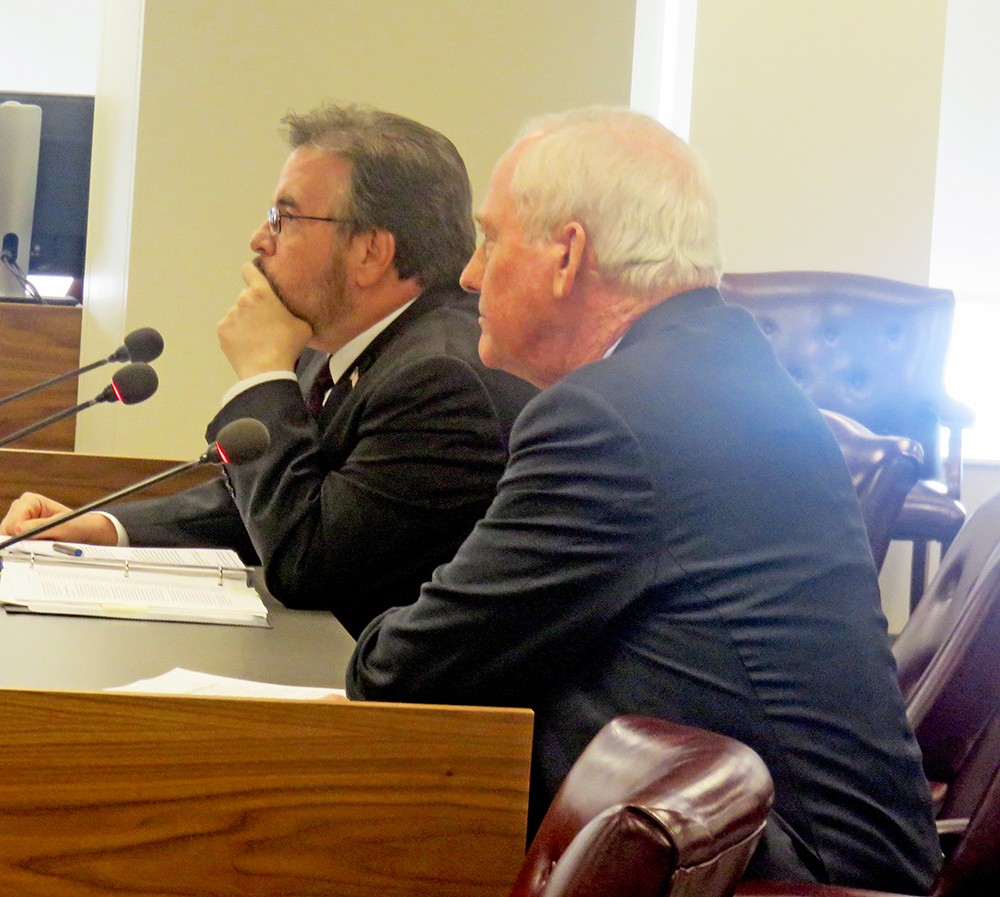

Attorney Koratsky and CAO Kennedy try to hold their own against Commission fusillade.

The administration had not consulted with the Commission on changing the 457 and behaved in a “proprietary” manner, senior Commission Democrat Walter Bailey objected.

In its peremptory behavior, the administration had revealed a very troubling pattern, freshman Democrat Eddie Jones objected.

The way in which the administration juggled numbers to justify a preference for Prudential over Nationwide had been a “work-around” that was “subversive of our accounting process,” Republican David Reaves objected.

“You’ve used the system to make the employees have only one choice,” Republican Terry Roland objected.

Republican Mark Billingsley and Democrat Willie Brooks raised a series of points objecting to specific line-items in the administration’s presentation, and several Commissioners concurred that the administration had not provided a clearly stated opportunity for an obligatory protest period regarding the new contract, nor did it permit sufficient time for such a period before signing the contract with Prudential.

Objection followed objection in a veritable cascade, and an increasingly testy Kennedy, abetted at times by county attorney Ross Dyer and assistant county attorney Kim Koratsky, insisted (correctly, it would seem) that the county charter made contracts the prerogative of the Mayor, that administration assessments of competing proposals were conducted fairly, that a legitimate protest period had been allowed for (though Kennedy could not say how long it had lasted or whether it had expired before the Prudential contract had been signed), and that the Prudential offer was, by however minute a margin, superior to Nationwide’s.

Kennedy’s clenching point, repeated numerous times, was that the arguments raging on Monday were moot: “The contract has been signed.”

Even so, after inviting representatives of Nationwide to testify and hearing them say that their company stood to forfeit at least $260,000 annually (a figure that seemed to attach an ad hoc financial value to the 457 contract), general government committee chairman Van Turner, a Democrat, introduced a resolution that made the case, point by point, that the Prudential contract was potentially “null and void” by virtue of several of its provisions as well as in its omissions.

Foremost of Turner’s contentions was that the 457 contract was a de facto ticket for profits well above a ceiling figure of $100,000 for the vendor, and that the profits derived ultimately from county employees, a fact placing the contract into the category of contractual obligations substantial enough to require Commission approval.

The administration team insisted again that the county charter was clear on the Mayor’s contracting prerogatives and that Turner’s resolution, which was tagged for legal vetting before next Monday’s public Commission meeting, was itself null and void.

Nevertheless, the Commissioners present voted 9-1 to support the Turner resolution, which might or might not turn up for renewed scrutiny on Monday, depending on how the legal vetting goes.

That discussion had taken just short of two hours instead of the 20 minutes originally allotted to it, and the final item of the day, also before the general government committee, concerned the aforesaid resolution allowing the Commission to engage a “special counsel” for limited and specific matters.

A Separate Attorney to Serve the Commission?

There ensued another robust and protracted discussion of well over an hour in which the Commissioners seemed to coalesce around a conflict-of-interest argument that was stated by Roland this way: “How can one person or entity serve two masters?”

The thrust of that was that, while Dyer and Koratsky insisted that they served the administration and members of the Commission with equal fidelity, the county attorney and his staff, though subject to an initial vote of approval by the Commission, were appointed by the administration and served entirely at the Mayor’s pleasure.

Moreover, said the two county attorneys, the county charter explicitly forbade a permanent counsel of the Commission’s own, though, by comparison, other local government units, including the Memphis City Council and the county Election Commission, were not so constrained.

Ultimately the various principals to the argument agreed to recess to review the legal implications of the Commission-attorney resolution for a Commission in executive session. At some point, between thirty minutes and an hour later, the county attorneys and a handful of Commissioners emerged from the back lounge where the executive session had taken place.

Turner announced that a general agreement had been reached that the resolution was unnecessary and that the Commission already possessed the ability to engage separate legal counsel for specific and limited needs, as indeed it had done when a previous set of Commissioners had hired attorneys to advise and pursue litigation during the school-merger controversy that raged early in the current decade.

Anti-climactic and incomplete as that concord seemed, it was enough to justify an adjournment, with all the arguments and counter-arguments to be either re-enacted on Monday or, conversely, declared resolved.

Whatever comes next, however, Wednesday’s prolonged committee session had brought into the open a long-simmering power struggle pitting the County Commission, as a body, against the Mayor and the county administration, and that struggle has by no means been resolved.