David Mamet is one of my favorite playwright/screenwriters. His rapid-fire, cadenced dialogue, especially in the right mouths — William H. Macy, Joe Mantegna, Rebecca Pidgeon, Gene Hackman — is a distinctive music. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his play Glengarry Glen Ross, which was made into a dynamite movie. And he is the director of the films House of Games, The Spanish Prisoner, State and Main, Oleanna, and others. Add to these accomplishments a number of books of essays on theater and film, and a handful of novels.

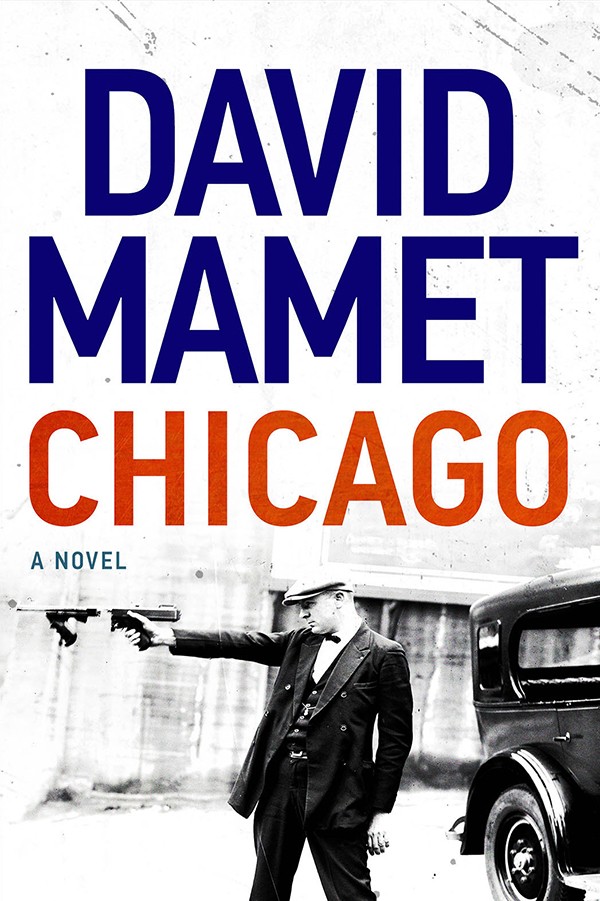

The good news about this new book, Chicago, is that it’s his best novel. It’s dialogue-driven, making it such a pleasure to read that it’s hard to put down. His characters talk like Mamet’s movie characters — sly, fast, and with a street-smart poetic pulse. The staccato interchanges, not unlike machine-gun fire, suit this tale of reporters and gangsters during the Al Capone era in Chicago. It’s a great crime novel: It moves briskly, and the story is gripping. It’s also often very funny.

Best friends Mike Hodge and Clement Parlow both work in the City Room of the Chicago Tribune. They’re seasoned pros, cynical, tough, and skilled, even when they find themselves wandering into the gray area between crime and justice. Mike has fallen in love, and Parlow rags him about it, goading him by saying he should be writing the sob sister column rather than covering crime. “A romantic is just a cynic for whom, as yet, the nickel hasn’t dropped,” he tells him.

But, when Mike’s paramour is killed right in front of him, in an apparent gangland slaying, Mike goes on a bender. “I killed her,” he says to Parlow. Mike’s guilt upends his career, and he is a lost sheep for much of the book. “He had loved his job, and its proximity to violence, which, he knew was like a drug, and he had loved the Irish girl; and now he was sick and grieving in that impossible grief of betrayal at having your heart broken by life.”

The gunman kills the woman and, just as Mike glimpses his face, knocks Mike out cold.

The twist is that the slaying may have nothing to do with Mike’s coverage of Capone.

Capone, known as Mr. Brown, exists only in the crisp, blackened edges of the story. But his shadow is large and deep, and corruption is so rife in the city, even on the paper, that attempting to find what’s true and what’s smokescreen is like working on a Gordian knot.

Eventually, Mike finds his footing again, and now he has revenge on his mind. The story moves through the murky alleys of 1930s Chicago. There are hoods galore, cops — some straight, some crooked — and a particularly charming whorehouse, where much is known and only some of it revealed. Mike is a known quantity in all these places, and he’s comfortable in the dirt. He learned to kill in the Great War, and he recognizes that it’s still in him.

The story is episodic but builds accumulatively toward the only kind of sense these types of stories make. As Mike collects clues, more people are murdered. He’s not sure whether he’s up against Capone or the Irish Mob or something more esoteric, a crime which has nothing to do with the Mafia. “The weakness in the Mafia,” Mamet says, “was the absence of legitimacy. Anyone with sufficient ambition could rise through obedience and violence; but there was, culturally, nothing to check his rise.” Fans of Boardwalk Empire will find much here to admire.

As with Mamet’s intricate crime films, there are stories within stories. Chicago glistens with fascinating details, scams, anecdotal red herrings, beautifully rendered asides, and gorgeously wrought digression. The plot, which does have a satisfying denouement, is almost secondary to Mamet’s way with language, especially his crackling dialogue. Sometimes, if you concentrate too closely on the plot — which is, after all, similar to Hitchcock’s idea of the McGuffin — you may miss the author’s playfulness, his skill with a sentence, and his love for arcane information.

It’s Mamet. It’s underworld characters. What else do you wanna know?