Follow that big, muddy Mississippi River all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, and you’ll find a dead zone the size of New Jersey.

Nutrients found in everything humans dump in the river — sewage, agricultural runoff, industrial waste, and more — stimulate the growth of algae, which sucks up much of the oxygen out of the water, killing fish and marine life in “one of the nation’s largest and most productive fisheries,” according to the United State Geological Survey (USGS).

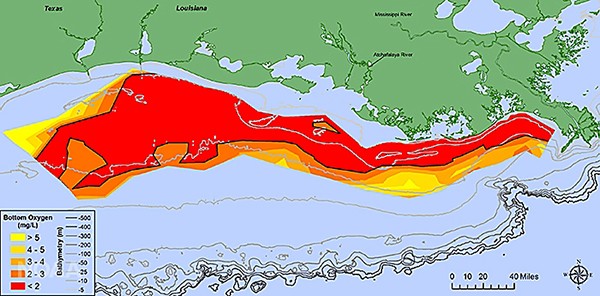

That dead zone this year was 8,776 square miles, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The toxic plume stretches from the tip of Louisiana’s boot to the Texas coast, and in it, you can find Tennessee.

The state ranks seventh nationally in the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus, the nutrients that mainly contribute to the dead zone, it puts into the Mississippi River, according to figures from the USGS. The state is responsible for 5.5 percent of nitrogen in the river each year and 5.3 percent of the river’s phosphorus. Illinois leads this list, contributing a total of about 29 percent of those dead zone nutrients.

Most of the nutrients come from farms, especially from corn and soybean production, according to the USGS. Farmers spray fertilizers and other chemicals on their crops, and rain waters carry them into streams, which eventually drain into the Mississippi.

Nitrogen levels in the river were near the highest levels since scientists began measuring it in the river in 1997. Couple that with heavy rains in the Midwest earlier this year, and you get the record-breaking dead zone, according to NOAA.

Efforts are ongoing to reduce the pollution and shrink the dead zone. A federal task force formed an action plan in 2008 and has reported its work to Congress every year since then. Also, back in 1997, the federal government asked farmers in the Mississippi watershed to voluntarily reduce their pollution levels.

“The latest Mississippi River water quality measurements demonstrate that spending $46 billion since 1997 to encourage farmers to reduce farm pollution voluntarily simply has not worked,” according to Emily Cassidy, writing for the nonprofit Environmental Working Group.

The river is a funnel that drains about 1.2 million miles of all or parts of 31 states and two Canadian provinces. Renée Hoyos, executive director of the Tennessee Clean Water Network, said the river drains about one-third of the nation, and the nation uses it as a “sewer.”

“By the time it gets to Memphis, it’s in pretty bad shape because it’s at the bottom of different sources of pollution that’s come to us from as far away as Montana,” Hoyos said.

Memphis has oft-times made that Mississippi River water worse. The city now operates under a 2012 federal consent decree after a number of agencies alleged the city illegally allowed its sewer system to overflow into the river. In 2016, the city’s system spilled millions of gallons of untreated wastewater into the river. (See our cover story for more.)

Tennessee is not alone, though. In a 2016 study, the Mississippi River Collaborative found that no state has effectively reduced its nitrogen and phosphorus pollution. And it may not end soon.

“I honestly can’t see the [Environmental Protection Agency] under the Trump administration taking the steps necessary, such as setting enforceable limits on dead-zone-causing pollution, to reverse this alarming trend,” said Matt Rota, senior policy director for the Gulf Restoration Network.