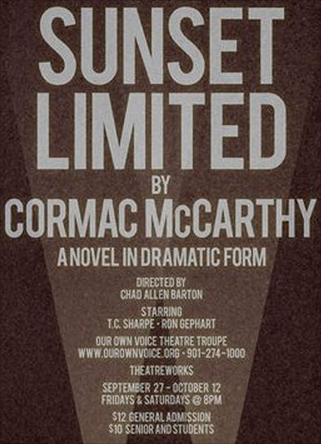

I’m not especially happy with how Sunset Limited is being billed. When Cormac McCarthy’s dialogue originally appeared on stage, critics were quick to point out that, great lines notwithstanding, it lacked action and was more like a stoned dorm-room conversation than a play. When it was published as a book it was described on the cover as a “novel in dramatic form,” hedging against the fact that it wasn’t quite a novel, nor was it a play, exactly. And this last description is how it has been described in promotional language for a show produced by Our Own Voice theater company. In this case the language is supposed to tip us off to the fact that what’s in store isn’t quite a full production, but is more fully realized than the average “staged reading.” To my mind it fails to accomplish this. Or to even get close.

I happen to like staged readings. They let audiences experience plays in a living context that, for whatever reasons, might never be produced. And they can help producing bodies realize potential and gauge interest in newer or more obscure works.

I like readings even more when they are as complete as this one is, but can still understand why someone might feel the need to dress up the concept to attract skeptics.

Sunset’s opening is gorgeous. It takes off like a bullet train with blinking red lights, clanging bells, then a burst of white light. And then, as eyes recover from the shock, the image of the actors fades into view. And their scripts.

Ron Gephart— book and all— is perfectly cast as “White” the otherwise unnamed professor. White is a laconic, sardonic depressive bent on self-slaughter, and Gephart brings a quantity of bitterness and rage to the table and keeps that potentially explosive pairing at a steady smolder throughout the night. His acting partner, the almost always excellent TC Sharpe, is merely effective. But he’s got a lot more words than Gephart— probably more words than Hamlet for that matter — and is more tied to his script.

It’s frustrating to see perfectly cast performers getting so close to a finish line they’ll probably never be allowed to cross. It’s even more frustrating to see an author of McCarthy’s caliber ( All the Pretty Horses , No Country for Old Men, etc.) hobbled by tired cliches.

The story in a nutshell: After attempting to throw himself in front of a train called the Sunset Limited, White is taken back to the rundown slum apartment of his savior Black, an ex-con and murderer who has found God and now works as maintenance man when he’s not skipping work to do good deeds. White is a depressed atheist with no faith in God or his fellow man. Black is a textbook example of an American entertainment stereotype commonly described (and not without controversy) as the “magical negro.”

Black came from out of nowhere to save White, who swears he looked to make sure the platform was empty before attempting to take his his own life, and there’s some slight suggestion that Black might be an angel. Later in the “play” Black accurately and unbelievably pulls off a Kreskinesque mentalist stunt by writing down what White is going to say before he says it, leaving White— and the audience— to wonder “how?” In addition to these seemingly magical feats, this older, unrelentingly wise, and uncommonly cheerful ex-con does what he can to bring his lost brother White back into the brotherhood of man.

After my first brush with Sunset, a story that suggests that academic learning might separate us from emotional learning, and the childlike acceptance that helps us find God, all I wanted to do was sit down with McCarthy and watch Preston Sturges’ film Sullivan’s Travels.

In Sullivan’s Travels Joel McCrea plays an educated and optimistic young screenwriter who thinks Hollywood movies are too shallow and should show Americans the depth and breadth of human suffering. After a series of unfortunate events that result in false imprisonment and hard labor this bright optimist comes to understand, without ever having to explain, that Disney is its own kind of opiate, and for those who suffer, as merciful as Morphine. Or religion. Or whatever gets you through the rough patches, soul intact.

Unlike Sunset, Sullivan’s Travels is a film that, while not blind to race, or religion, puts these hot topics in supporting roles. When McCrea and his fellow prisoners encounter Disney, it’s during “movie night” at a black pentecostal church, where the pastor cautions his congregation not to make the prisoners feel unwelcome. It is, perhaps, a more Jesus-like way to share faith, and in terms of entertainment, a lot less tedious than this more-contemporary phenomenon where older black characters are Bible wizards directly connected to the supernatural.

I use Sullivan’s Travels as a point of comparison because it also helps us to see some things that McCarthy may have gotten right, critical reception notwithstanding. Unlike other similarly heady and equally inactive works by authors like Beckett and Sartre— works whose dramatic qualities have also been scrutinized— there’s nothing alienating about the setting or the language of Sunset Limited. In that regard maybe it’s a working class Godot with one character stuck on the line “Why don’t we hang ourselves.”

In short, for all of its obvious problems, and its potential to plunge headlong into cliche, Sunset Limited deserves a fair shake. The opportunity to see two excellent actors read through it live only highlights the fact that this isn’t that. But it could be.

I’m grousing, not dismissing. This isn’t a bad night of theater. But to minimize disappointments, you need to know exactly what you’re getting into.

For more information, here you go.