There’s an anecdote about two writers, Hal and Al, who sit down to discuss their work. Hal pulls out a 1,500-page novel and hands it to Al, who flips through it and says, “Geez, Hal, this looks good, but it sure is long.” “Well,” responds Hal, “I didn’t have time to write something short!”

Point being, of course, that it is harder to make something good and simple than to make something good and complex. Longtime Memphis artist and educator Dolph Smith’s most recent show at the Cotton Museum is a testament to this idea. The exhibition — called “Parting Shots” because it is also (supposedly) Smith’s final show — features paintings, drawings, and sculptures that Smith pares down into their simplest gestures.

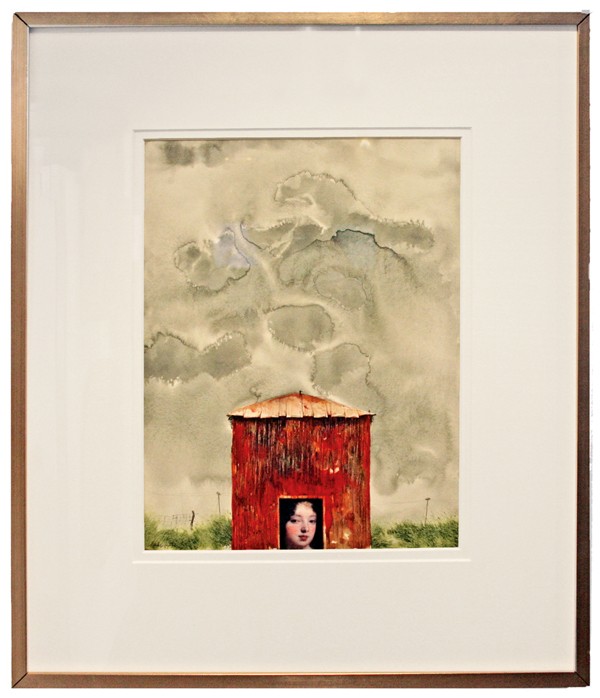

Rosie’s Window, part of Dolph Smith’s “Parting Shots” exhibit

Smith, who spent his teaching career at Memphis College of Art, is best known for his deeply hued watercolor paintings of Southern barns. Smith’s barns are myth-steeped and romantic without being wistful. The artist and craftsman’s work has a dark incisiveness that places his simple landscapes somewhere outside the literal. It is hard to see his barns, pitched under bleeding skies, without also seeing their hollowness. The structures are an empty point of contact with a big, and not necessarily kind, beyond.

“If you look at any one of these paintings,” Smith says, “you’ll see that watercolor is an act of nature. I could never paint these skies, but if you have water and you put a color on it, it will move. As it moves, it takes color with it. It will settle into the interstices of the paper. I collaborate with nature.”

“Parting Shots” contains some works from Smith’s early canon, as well as much more recent sculptural pieces. After his 1970s success as a painter, Smith says he entered a period where he felt as if he were artistically repeating himself. In response to this, he became a paper maker. “When you begin to build up surfaces,” says Smith about this process, “you feel like something is coming out to join you in the real world.”

Layered paper works such as Will We Know What’s Gone Before feel less like they are built to join us in the real world as they are to draw us more effectively into a removed and transcendent space. In the piece, graphite-coated handmade paper is sculpted to form a pile of sunken-looking detritus. A paper ladder grows out of the graphite detritus and morphs into a brightened, wooden version of itself — a version that is, once again, disrupted by the graphite toward the top of the work. Several other wooden ladders also appear, and disappear, near the piece’s center.

Will We Know What’s Gone Before takes place in a dream where, perhaps, the viewer climbs an endless ladder out of a silo, a factory, a well — and mid-climb, is caught in a strange, bright light. This dream-logic is echoed in a similarly constructed work, The Pearl Divers of Tennarkippi, in which a wooden boat sails over the cast-paper remnants of a wooden house. The work recalls sunken ghost towns or a hurricane-flooded gulf. The pearls, if they are there, remain hidden.

Smith’s works are not about place, though the works bear the signs of a storied South. Rather, pieces such as Parting Shot V: Leaving the Nest and Parting Shot III: Nerissa Knotgrass leaves for new ground center around a sense of displacement — a doubleness or tripleness of place, realized through small frames and images that he places throughout the work.

Smith’s work is not elaborate. It doesn’t need to be. He focuses on simple moments of paradox that, though deeply complex, need little elaboration to be understood.