The noise drew Whit Washington to the chain stitch machine that would drive her course into entrepreneurship: a hum, a gentle, rhythmic drum of the push and pull of the thread through the fabric.

“It’s very cozy, homey, like you feel like you’re sitting by the fireplace,” she says. “And you know something’s being made. The noise makes me feel nostalgic and cozy in a way.”

It’s a noise that once filled the homes of her grandmother and her Cousin Minnie — “my mom’s great aunt or cousin or close friend, family, you know.”

“Me and my mom used to drive down to Mound Bayou, Mississippi, when I was a little kid … to visit her in her kind of little shack home, but just like the cutest little home. We’d always bring fried chicken down there and eat with her and she had her turnip greens going and growing in the back.

“And in the back room, she had this whole quilting room someone made for her out of wood, and she would hand-sew all of these quilts and these beautiful patterns and use whatever scrap fabric that she had.

“She was quilting until she was like 100 … elaborate, beautiful, handmade quilts, and looking at them, you can just see the little stitches and her hand in it.”

These quilts captivated and influenced a young Washington, yet work like this done by Black women like Cousin Minnie often goes unnoticed by many, relegated to the background, left for memory boxes. Yet grandmothers and mothers will teach their grandchildren and children to sew, knit, crochet, cross-stitch, quilt, patch — examples of textile or fiber arts, those utilitarian practices that are needed to keep us warm and clothed for millenia.

Over the years, textile arts have been crafted primarily by women, and mostly by women of color, and so have been neglected from mainstream art narratives. While speaking to the website Artsy, April Bey, a California-based multimedia artist whose work explores themes of Afro-futurism, feminism, post-colonialism, and more, said, “Historically, there’s a perception that, because women have been denied easy access to academia, when [domestic labor] is involved, their work doesn’t hold intellectual value. Sewing and textiles, weaving and craft-based disciplines tend to carry a feminine nature that has been seen as maternal and thereby not as intellectual or serious as the praised painter.”

Yet on the verge of the feminist art movement of the 1970s, artists sought to flip that narrative and use textiles to question the world and their position in it. But then and now Black textile and fiber artists remain under-shown and underrepresented, forgotten in the weeds of intersectionality.

In Memphis, artists and institutions alike are seeking to correct that narrative and highlight Black women artists and artistry in fiber and textiles — from hosting exhibits to continuing, reviving, and reimagining art forms that have nearly been lost.

Woven Stories

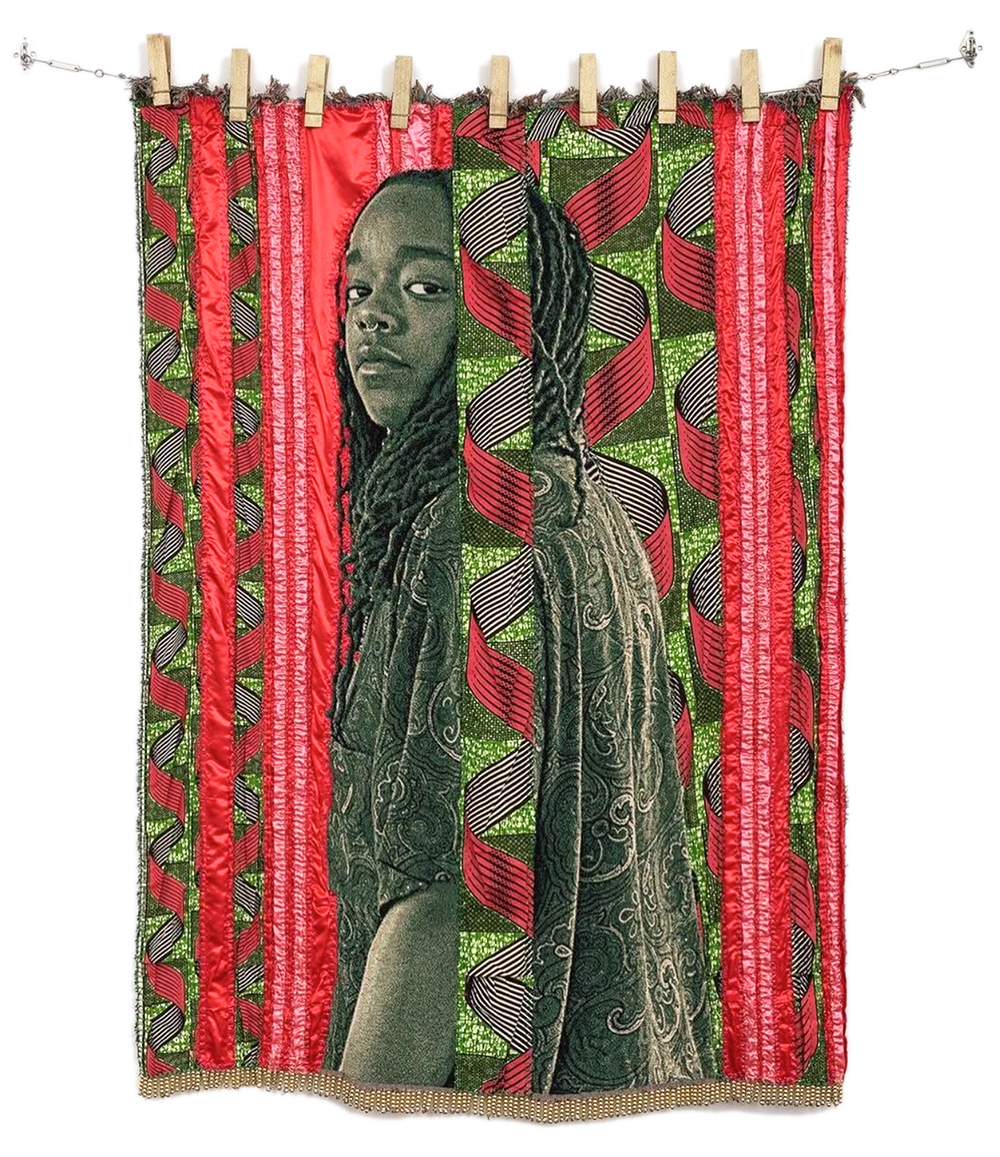

April Bey is somewhat of a celebrity when it comes to textile and fiber arts — at least to Jayla Slater, a professor of fashion and apparel design at the University of Memphis and curator of “Unraveled,” now on display at the Art Museum of the University of Memphis. “Unraveled” opens with Bey’s work, I Was Just An Alien That Came Down From the Sky to Save Your Dumb Behind, which hangs at the entrance against a bright green wall.

In the 82-by-60-inch woven blanket, the figure of a woman peers through overlapping panels. She overlooks her shoulder, her gaze staring directly at the viewer, as if she’s inviting us into her world, the blanket becoming some kind of portal into the world Bey has called Atlantica. Atlantica is “a glittering, imagined utopia where Black queer excellence thrives unbothered,” reads the wall text.

The portrait happens to be of Jessi Ujazi, a Memphis native, on Juneteenth — “a day that holds ancestral weight, radical joy, and future-facing liberation.”

Save Your Dumb Behind in “Unraveled” (Photo: Courtesy the Artist)

“It was just so fitting,” Slater says of the coincidence.

“Unraveled” is a sort of Atlantica, a place where Black women can share their joy, their stories, unencumbered. “It was really special to be able to bring this show to Memphis because we’ve not had anything like this,” Slater says of her solo curatorial debut. “I really wanted to celebrate Black women creating work with textiles.”

Textiles, in particular, hold a special space in Black heritage and culture. “A lot of first experiences that anybody has with relics of their culture is tactile things — especially for Black people and for Black people who are members of the diaspora outside of the continent, who are descendants of enslaved people,” Slater says.

“A lot of written history doesn’t exist, and so a lot of the relics of culture are physical items and a lot of times that comes in the form of textiles, quilts, old pieces of clothing, and furniture or pillows that have been saved. So there’s a cultural component for this show because all of these people are doing their thing, connecting with their people, creative work, just having fun with the medium. It’s really special.”

For an artist like Memphis-based Felicia Rachelle Wheeler, for instance, that looks like using the peyote stitch, a beading technique used in historic and contemporary Native American cultures, to recreate a childhood photo in Way Up There. This was the first time she’d used the peyote stitch, and it took her more than 100 hours and 10,000 beads.

Felicia Wheeler’s Sarah Lou in Pink is on display in “Unraveled.” (Photo: Courtesy The Artist)

The piece, completed in 2024, combines this peyote stitch with crochet. “Because she’s of mixed cultural heritage and her Native American side used the peyote stitch to create beadwork, she is mixing together all these forms that she’s learned from the matriarchs and her family,” Slater says.

Significantly, Wheeler isn’t the only artist exploring memories and family in the show, nor is she the only Memphis artist among national and even international artists in “Unraveled.” “It was a no-brainer [to include Memphis],” Slater says, “especially connecting to my own roots through the curation. I mean, my roots are here, and these women are telling the story of Memphis.”

Traditions Broken

For Janessa Ladson, Memphis has been a place of artistic rebirth. When she graduated from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, with her bachelor of fine arts in 2023, she fell into a bit of a creative drought. “I felt stuck. I didn’t know how to exist outside academia,” she says.

But when Ladson and her fiancée moved back to Memphis in 2024, “I felt this sense of urgency come back to me,” she says. “I think also being back in a place where I saw myself and the different parts of my person and identity reflected more in my community felt as if there was this great igniting of my creative view.”

She found herself turning — or rather, returning — to a language that first fascinated her as an undergrad: weaving. “When I first started, I definitely was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to be an abstract girly. I’m going to sit in that.’ And not from a fear of representational work or anything like that; I think that I didn’t have any sense of personhood. But because I sat in abstraction, I used all of this collected hair and I decided to build this little language.”

Hair, to Ladson, has always represented herself. “It’s such a large piece of me, in the way that people see me,” she says. “Lots of people pay attention to my hair, and so then I pay attention to my hair. And I think going to predominantly white schools, I am confined literally into everything that existed in those schools. I was a Black girl with bushy, curly hair, and all of my friends were really cutesy white girls with beautiful blue eyes and blonde hair. So I became more aware that it’s almost my personhood. … I think because people see me as my hair, that felt like another way to paint myself.”

And so hair became her paint, her medium; she buys bundles of it at beauty shops to weave around cyanotypes of old family photographs she’s carried with her everywhere she’s moved in a Ziploc bag. “I’m not exceptionally close with my Black family, and most of the people on my mother’s side have passed away,” Ladson says. “I don’t remember a lot of things, but I have this photo and I have evidence of a relationship. And so it’s like putting myself back into the narrative.”

These portraits that mingle hair weavings and family photos have finally allowed Ladson to see herself represented in media — something she’s longed for since she was young. “I wanted to take up a lot of space,” she says. “So when I discovered weaving, I realized that no matter the size, it’s still time-intensive, it’s still laborious, and it still lasts as long.”

By and large, Ladson’s self-taught in her weaving, resorting to library books and asking for advice here and there from a weaving group that meets at Crosstown Arts. “Things of fabrication and stuff like that, I feel like a lot of that is passed down. It’s this thing that you learn from your mom who learned from her mom, who learned from her mom. I didn’t have any of that,” Ladson says. “My relationship to weaving is very untraditional in a sense that feels really fitting, though, because my relationship with my family or lack thereof is very untraditional and dysfunctional.”

For “Unraveled,” where she has a few of her signature weavings displayed, she created The Greater Part Has Been Removed, as part of her creative rebirth in Memphis. “To be with other Black women is amazing,” Ladson says. “I think it goes back to the idea of me being super inquisitive about other Black women’s experience and me being a baby in terms of knowing and not knowing the things. It’s just super magical. I love to see other Black women who are working in the same textile, fiber arts.”

In a few weeks, Ladson leaves for New York University for her master’s in arts administration. “There’s like no data showing Black women in managerial positions within the arts infrastructure,” she says. “I wanted to make room for myself, and when I make room for myself, I make room for everyone else.”

Purpose in Nostalgia

“This is the biggest show I’ve done,” says Kid Kardiac. “I wanted an opportunity to show my range in a place where it made sense. A lot of my pieces have been put out on Instagram, on my website, just for people to see from inside my house.”

Kardiac is mostly known for tufting rugs and wall-hangings, but for “Unraveled,” the native Memphian ventured into incorporating other elements, like a frame, a punching bag, and carpentry. As always though, she turned to those who inspire her for her subjects — typically Black artists, musicians, and sports figures, and in this case, Muhammad Ali, André 3000, and Skateboard P.

“My art is about capturing moments,” Kardiac says. “With a fast-paced society, things get forgotten very quickly.” Tufting allows her to bring a moment beyond a photo, to stretch its lifetime and to bring a new experience to it — in the consumption and in the creation.

The process is laborious and time-intensive, considering planning and editing and the physicality of it all. But, to Kardiac, “It’s almost like a calming thing for me. It feels like therapy in a way.”

She tufted for the first time during the Covid lockdown simply because she couldn’t find a rug she liked. She’d never experimented in visual arts before, her prior creative pursuits being in music. She’d never really drawn, but she was confident she could learn this new skill and that she could improve until she was satisfied. “There wasn’t anything to look up [for tufting],” Cardiac reflects. “I was just finding really old videos of people using the technique.”

But soon Kardiac was posting her creations to Instagram and she started receiving commissions. “It really was a blessing in disguise,” she says. “I didn’t really have a sense of direction as far as what I wanted to do, and so it kind of gave me purpose.

“And then I shifted my focus on work to create my own pieces, and people would buy those as well.”

These days, Kardiac’s not using her tufted pieces as rugs; she’s hanging them on the walls of her home or exploring new ways to make use of the material — like in “Unraveled.” But even as she dives into new mediums, Kardiac says she doesn’t want to stray from her roots, her tufting. There’s something about it, she says — the sensory element, a sense of nostalgia, coziness. “I want to bring it to another level.”

Embracing the Culture

Whit Washington found her calling with the chain stitch machine, the one that made all the noise. She had been working various jobs in New York City while at Parsons School of Design. One of them — her job customizing clothing at Nike — had a chain stitch embroiderer. “I was like, ‘That’s it. That’s what I’m gonna do.’”

It took her six or maybe eight months of searching, but she found a chain stitch machine of her own from some guy who got it from Egypt. “Apparently, I really like to learn how to do tedious difficult things,” Washington says. “When I got the machine, I only saw one other Black woman on Instagram doing it, so I reached out to her and I was like, ‘Can you teach me how to use this machine?’”

From there, she took her new-found skill to new jobs, and when she came back home to Memphis during the pandemic, she hit the ground running with an embroidery business that would become Pile of Threads, with wholesale and customizable products.

Mostly, her work centers around the Black experience and embracing Black womanhood. “I’m really enjoying making things for Juneteententh,” she says, as an example. For Memphis Fashion Week at the Memphis Brooks Museum, she also embroidered pieces celebrating and remembering the Historic Clayborn Temple and the sanitation strike of 1968.

Washington also does pop-ups, where she demonstrates her craft, customizing pieces on the spot, monogramming bandanas or stitching upcycled caps with flash icons. “I don’t mind being on display,” Washington says. “So embroidery is utilitarian, and it can even be performative.”

For these events, she uses her vintage machine. “I’ve always been really nostalgic,” she says. “There’s a feel to it where it’s like, ‘Wow, this is a 100 years old. Who used this before me? What were they making?’

“It’s almost reviving an art because it did kind of lose favor with digital machines. It’s just like, ‘Okay, this is faster, quicker for business.’”

Because of this, the vintage machines have been hard to find for Washington, and getting them repaired is even more difficult. “There’s this lone Facebook group where I would put a video in there and they would answer pretty immediately. But I learned how to become my own mechanic on the machine.”

In Tennessee, at least as far as Washington is aware, there are only two other comparable chain stitch embroidery businesses: RangerStitch in Nashville and Kait Makes in Chattanooga. “Eventually I wanna have a band of stitchers,” Washington hopes. “I’m kind of bringing the energy to Memphis, and it’s trying to carve out new paths and new lanes for artists.”

These days, Washington has also been in school for welding, a craft she hopes to one day intersect with her chain stitch. “There’s not a lot of women in welding, or in the trades period, so I’m like, ‘Come on, let’s be a trailblazer in another way.’”

And as her welding instructor at Moore Tech told her, “Welding is like sewing with the sun.”

Making Connections

In October, the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art will open its own exhibit honoring Black textile artists, specifically Black Southern quilters. Having originated at the Mississippi Museum of Art (MMA) in Jackson, Mississippi, “Of Salt and Spirit: Black Quilters in the American South” will feature highlights from MMA’s and American photographer and collector Roland L. Freeman’s collections of handmade and machine-stitched quilts. “Our iteration of this exhibition will … [also] tie it back to our Memphis community,” says Kristin Pedrozo, Art Bridges Fellow at the Brooks. “Memphis is definitely no stranger to [the quilting] tradition.”

“Many of these women are from rural areas, folks you would see every day, but individuals that folks may not perceive as artists,” Sharbreon Plummer, “Of Salt and Spirit” curator, said to the Mississippi Free Press when it first opened in Jackson. “It’s important for me to celebrate the contributions of these women as artists, as everyday archivists and individuals who inspire so many.”

Pedrozo admits, “Quilts aren’t typically shown as often as the traditional style of paintings or sculptures are in the museum setting. It is a craft form, and it is one of those craft forms that are extremely labor-intensive and have a lot of intentionality behind them, and on all levels, is a form of artistry. A lot of people around the area have grown up seeing a quilt, either in their home or family homes, so it’s something that we really like about it. It’s a very accessible art form.

“And I do think, in this moment of the museum world, there’s been a lot of resurgence with showing off craft as an artistry and appreciating it a little bit more.”

For this show, each maker or each community that’s made a quilt has been accounted for. “It’s very common for a lot of old historical textiles to have very little information about its maker,” Pedrozo says. “It’s hard to separate the quilts from their makers, so we placed a lot of importance on the people who are making them.”

Quilts, after all, are personal items, made for personal use, made with care and attention — as are most textile arts. These are slow processes, where the maker’s hand is often shown through their stitches, weaves, and knots.

“There’s a certain intimacy in it,” Ladson says. “[Art-making] takes away how I want to be perceived and I don’t censure myself. And so when I take away the responsibility and that burden to be accepted, I practice vulnerability and intimacy with myself, which is something I’ve always run from my entire life. … When I’m making, it’s like self-care.”

This burden of perception is particularly sharp for the Black woman’s experience. “Black women are the most forgotten in history,” Ladson says. “They’re always overlooked and misrepresented. There’s so much distrust in Black women. In the way they are painted, sort of culturally, socially, politically, they’re very othered.

“Maybe that’s also why I’m always in awe when I find that there is this whole world of Black women creating and successfully creating.”

From Washington’s Pile of Threads, to the quilters in the Brooks’ “Of Salt and Spirit,” to AMUM’s “Unraveled,” to fiber artist Brittney Boyd Bullock, to tailor Cari’s Closet, to crocheter Hooked by Candice, Black women in Memphis are succeeding in the textile arts. “A lot of textile artists in Memphis fly under their radar,” Slater says, “because our scene is craft. There’s a quilter practically on every corner or somebody that’s fixing up clothes or doing these elaborate wigs for the drag queens.

“I hope people come away [from ‘Unraveled’] feeling really good. The show is a celebration, and so I hope people can feel that for one, and for two, maybe go pick up some textiles.”

“Unraveled” at AMUM closes August 16th. Admission is free. “Of Salt and Spirit: Black Quilters in the American South” opens at the Brooks on Wednesday, October 1st.