Edward Carey’s first novel, Observatory Mansions, announced the coming of a new American fabulist. It may have been the best first novel since Steven Millhauser’s Edwin Mulhouse. And like Millhauser, Carey’s inventiveness was joyous and full of marvels, like a bookish visit to Aladdin’s cave. His second novel, Alva and Irva, only cemented his reputation as a new Calvino. Little is his first adult novel in years, after a well-received Gormenghast-like young adult trilogy.

This new novel, as they say in a film’s opening credits, is based upon a true story. But the literary magic, the supreme storytelling, the novelistic pacing and design belong to Carey, and he dazzles. The Dickensian tale begins in Switzerland, in the 1760s, when a young orphan girl, Marie, becomes apprenticed to a Doctor Curtius, who has washed out of medical practice, only to begin an eccentric career based on making figures in wax. Marie is under five feet in height and becomes known as Little, a moniker at times affectionate, at times demeaning. “Little ill-facedness, little minor monster in a child’s dress … little thing … little howl … little crumb of protruding flesh … little statement on mankind,” one nasty man calls her. Little’s story is fraught with horrors, then becomes a mix of horrors and enchantments.

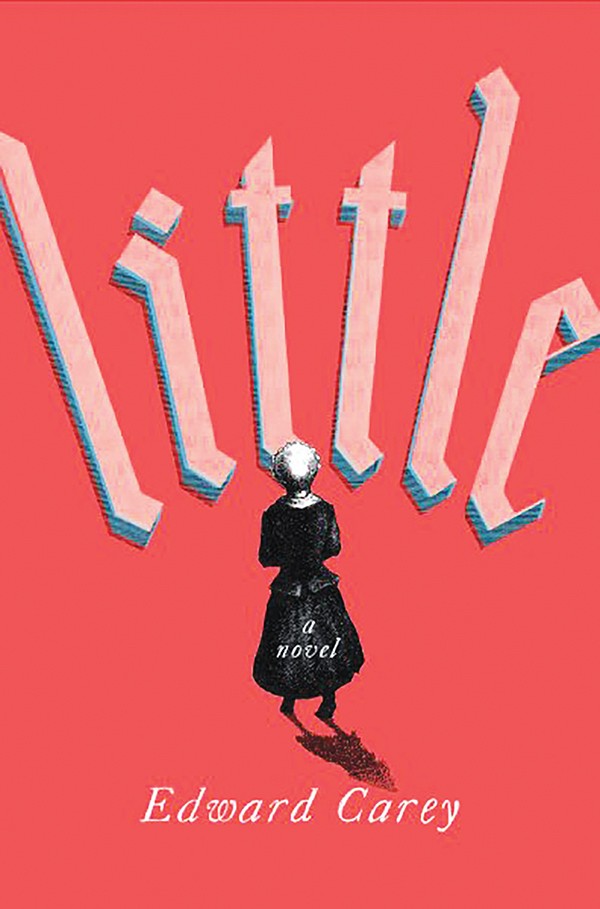

Little is voiced in first person by Marie, and she is an engaging narrator. She says, “This is the story of a shop. The story of a business, of its highs and its lows, of its staff coming and going, of profit and loss, and sometimes of the outside world and the people that came knocking on our doors. So then. Let me explain.” She also illustrates her tale with chiaroscuro drawings, demonstrating the craft she has learned from the doctor, though the pupil soon outstrips the educator. Carey is an accomplished artist, and his illustrations add to the strange and eerie luster of the tale. The book’s pages are as lovely as a rill; the words wind around these intricate and arresting sketches. They remind me of the illustrations in some of John Gardner’s novels. I met Gardner once and asked him why he liked visuals in his novels, and he said, “Because every time you open one it’s like Christmas.”

Curtius’ art takes them to Paris where they take lodging with the Widow Picot, in her home called the Great Monkey House. She is one of the novel’s antagonists, an unpleasant woman who takes an immediate dislike to Marie and sets about to make her young life a living hell. “I loathed her utterly, then and always,” Marie says. “Can I describe my hatred for her? It would poison these pages.”

Meanwhile, the waxworks they’ve begun in the widow’s house have become a popular attraction. She wants to exhibit only the best people — she is a terrible snob — while Curtius is drawn to the criminal and the insane. The exhibition is yin and yang, heroes and villains, dark and light. It is this seesawing back and forth that propels the story, as Marie attempts to come into her own. It’s a bildungsroman, with the added twist that the hero is a woman, who must not only battle her tormentors but also the prejudices of a male-centered universe. Carey adds just the right amount of gothic seasoning to his tale. One can feel a bit of Bronte behind his descriptions of the various households and plain and fancy folk whom our protagonist finds herself among.

The historical background for this tale is the French Revolution, the same as A Tale of Two Cities. Carey’s version, seen through the eyes of a young woman coming into her own, is a masque with a colorful cast of real people, from Marie Antoinette to Jean-Paul Marat and Jacques-Louis David, from Rousseau to Robespierre. Carey’s vividly painted setting and equally vivid rendering of characters makes Little the kind of book you feel you are living within. When I finished, I immediately missed it. I wanted to listen to Marie a little longer. It’s also a story too large and rich for a 700-word review.

Little is the best piece of new fiction I’ve read this year. It is a marvel. It is like a Christmas present. Give it to yourself.