The Road

By Cormac McCarthy

Knopf, 241 pp., $24

Even in the small contemporary-fiction sub-genre we might call “The Post-Apocalypse Tales,” this new book by Cormac McCarthy, master of bleak, blasted landscapes, stands out. It is a wintry, hellish prophecy written in a terse, attenuated style perfectly suited to the backdrop of ash and ruin its nameless protagonists, father and son, traverse. McCarthy writes as if language itself is petering out, as stripped and barren as the countryside.

Thomas Mann said, “Language is civilization itself,” and in McCarthy’s collapsed world, there is little civilization left. The man and his son in The Road might be ghosts, doomed to walk the ruined Earth as witnesses. They might be ghosts, that is, if they weren’t condemned to an existence built solely on survival.

“By day the banished sun circles the earth like a grieving mother with a lamp,” McCarthy writes early on. It is this grieving mother who tempers the brutality of the subsistence life the author outlines here. She is not quite God. Even in the father and son’s hopeless quest for food and shelter, McCarthy finds the imperishable kernel of common humanity. His characters, who worry about being the only “good people” left and who seem to encounter the bad people over and over, are drawn beautifully and in such few words. McCarthy’s basic humanism shines through, even on this dead road, a road only, in truth, a dreamscape, a diminished leftover of paved optimism.

Cormac McCarthy

In their wandering, which is really a quest (though we already know that at the end there won’t be a city of gold or a grail), the father and boy scrabble through garbage — garbage already scrabbled through. They find a few houses, which offer brief rest. Occasionally, they find things, objects from the lost civilization. Mechanical things that will never work again. Toys once loved. And books.

McCarthy’s last book, No Country for Old Men, published a little over a year ago, received some of the worst reviews of his career. I was in the minority: I saw it as an exercise in thriller writing and thought it spare and mean and as fast-paced as a getaway car. Now McCarthy has followed it with what his fans may recognize as a return to his earlier, stark, haunting and haunted books, which now seem only a tune-up for The Road. I will say it plain: This is the best piece of fiction I’ve read this year, and it may be the best novel McCarthy has written.

I’ll not ruin the ending for the reader, but the story, which seemingly has nowhere to go, manages to conjure revelations and hope. Cormac McCarthy, the master of sinister, visionary landscapes, has created here a human and humane book, which, one can only hope, will outlast our worst visions and endgames.

— Corey Mesler

Twilight

By William Gay

MacAdam Cage, 300 pp., $25

Let’s go ahead and get this out of the way: William Gay’s Twilight is a straightforward novel. In an era where even “literature” has taken a fancy for the cute, convoluted, artificial plot device, this is a good thing. A number of authors seem to think that if their subject matter is obscure enough or if their narrative is slick enough, they can somehow elect not to say anything over the course of 300 pages. Gay avoids this trap by concentrating on telling the story first and foremost and letting his style evolve out of that goal.

In Twilight, teenager Kenneth Tyler discovers that the local undertaker, Fenton Breece, has become a little too intimate with the dead. The problem is that the only sheriff with any eye for justice lives in the neighboring county. To find him, Tyler must trek through an eerie backwoods while avoiding the hit man Breece has hired to cover Tyler’s tracks for good.

The way the plot unfolds is a little reminiscent of Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain, but what makes the story so effective is Gay’s masterfully controlled voice — a voice that has earned him the title of “the last genuine heir to Faulkner” from author and Rhodes College professor Marshall Boswell. That voice is just so natural. The narrative emerges from a collection of anecdotes that, pieced together, represent the collective memory of the small community where the story takes place.

This is not to say that Twilight is perfect. Almost every adventure story involving a teenager has to trudge through an awkward explanation of the obvious solutions to the central conflict before the plot can get rolling. Twilight is no exception. Tyler has some incriminating photos. Okay. Why not go straight to the police? Why not drive to the next town? Why not tell everybody about your evidence and be on your way? Gay deals with these questions, but a couple of times it’s obvious that he’s trying to get the action going. At least twice, for example, the action shifts because a truck doesn’t start.

These problems are superficial, though. Twilight marks a great success for Gay and proves that he’s much more than a passing figure on the Southern literary landscape. — Zac Hill

Nature Girl

By Carl Hiaasen

Knopf, 306 pp., $25.95

Honey Santana is off her meds again. She is out of work and up to mischief. Disgusted with telemarketers who persistently interrupt her suppertime and conversations with the 12-year-old son she adores, Honey tracks down one especially rude, oily voiced caller and contrives to teach him a lesson in respect.

Carl Hiaasen

Also unemployed after calling Honey a dried-up old skank (she had berated him for being a professional pest), Boyd Shreave is aware of the irony when he accepts an offer to take an eco-tour of the Florida Everglades in exchange for sitting through the accompanying sales pitch for land breathtakingly close to the tracts he had peddled during his brief tenure with Relentless, Inc. There is little reason to stay in Fort Worth (not even his wife and mother like him) and several arguments for using the free plane tickets provided by Honey’s ex-husband. (Boyd’s mistress, Eugenie Fonda, doesn’t like him either, but she’s always up for an adventure and the hope for better prospects.)

Sammy Tigertail, half white and half Seminole, has secluded himself in the Ten Thousand Islands to find peace with his heritage and harmony with the Gibson guitar his half-brother snagged from the local Hard Rock establishment. He also needs to come to terms with the ghost of a man whose body he has improperly disposed of in Lostmans River.

Honey’s party and an entourage of which she is unaware, as well as an FSU coed and a spirited evangelistic group, encamp on Dismal Key, the island where Sammy Tigertail had expected to find solitude but discovers instead that life at its barest can be as intrusive and perturbing as a telemarketing call.

Nature Girl by Carl Hiassen is brightly jacketed; its numerous characters and exotic landscape deftly drawn. Tidbits of Seminole history lend plausibility to a series of outrageous events. The book is fun, especially on a cold day when prickly heat and insect-slapping are the stuff of a distant place. — Linda Baker

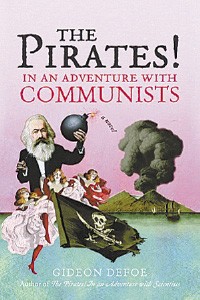

The Pirates! In an Adventure with Communists

By Gideon Defoe

Pantheon Books, 166 pp., $15.95

Imagine watching a Scooby Doo-style mystery acted out by the cast of Monty Python in pirate costumes while you’re high on some dank weed. Or skip the weed and forget about imagining anything. Read Gideon Defoe’s The Pirates! In an Adventure with Communists, which is similar to the above scenario.

The third book in a series of nautical adventures, Defoe’s laugh-out-loud book follows the escapades of a ditzy, narcissistic Pirate Captain and his crew, who are identified by their defining characteristics (e.g., the pirate with the gout, the pirate with bedroom eyes, the albino pirate, etc.).

In a case of mistaken identity, the Pirate Captain is arrested in Victorian London when his ship docks for a shopping trip. The police have taken the captain for Karl Marx. Once the mistake is cleared up, though, the captain encounters the real Marx (whom he later mistakes for a hairy sea creature due to Marx’s abundant facial, chest, and back hair).

But someone has also been asking people to do unspeakable acts (like drowning kittens) in the name of communism in an attempt to give Marx a bad name, so the captain agrees to help Marx escape his bad rep.

The crew sets sail for France, where they discover a similar plot to destroy communism. (People are raising the price of tiny dogs, and dancing girls have stopped going panty-less in favor of bucket pants, all in the name of communism.) Together Marx, Pirate Captain, and his crew (who tend to describe things in terms of typefaces) set out to unmask the culprit.

Throughout the book, Defoe manages to mix nonsensical jokes with subtle social commentary. Take for example, this paragraph:

“Back in those days the Thames wasn’t the beautiful crystal-clear colour it is today, and it didn’t have children splashing playfully about on its sandy banks. It was grey and drab and had old shopping carts floating in it. And you couldn’t cup your hands in the river and drink its delicious water like you can now, on account of all the pollution. Pollution came from factories, because the factories of Victorian times didn’t make iPods and Internets and shiny DVDs — they made large clouds of black smoke, which were sold to countries that didn’t have much in the way of clouds, like Africa.”

Defoe’s humorous prose is also peppered with footnotes containing useless trivia. For example, did you know that the armadillo has the longest period of REM sleep? Or that the biggest flag in the world belongs to Brazil and weighs about as much as two fat manatees?

Equal parts witty and absurd, The Pirates! In an Adventure with Communists will put a smile on the face of even the stiffest reader. If the book were a typeface, it’d be comical — like Chalkboard Bold.

— Bianca Phillips

Vice: Dick Cheney and the Hijacking of the American Presidency

By Lou DuBose and Jake Bernstein

Random House, 262 pp., $24.95

To be sure, there is a shortcut or two in this summation of the life and times of the current vice president of the United States.

But, if it is something less than a full-scale biography, this concise little book is also something more than a mere brief against a public figure — one whose enduring effect on the life of the republic is summed up, as the authors see it, both in the title word “Vice” and in a subtitle that all but charges Dick Cheney with high crimes and misdemeanors.

Consider it a Cliff’s Notes for the hitherto uninformed, a Dick Cheney for Dummies. And for a final chapter that may lay too much emphasis on the pending (and likely anti-climactic) trial of former Cheney aide Lewis “Scooter” Libby, readers can substitute an alternate resolution: the judgment just rendered by the American electorate.

For the two Texas-based authors, veteran muckrakers and foes of the current administration, make a compelling case that the complex of national-security and foreign-policy issues apparently repudiated in last month’s elections are to a large degree the creations of Cheney. That includes not only the ill-fated Iraq war but also a variety of assaults against habeas corpus and due process and a policy-making apparatus that has all too often bypassed not only Congress but, the authors suggest, President George W. Bush himself.

DuBose and Bernstein — the former a collaborator with Molly Ivins in the anti-Bush screeds Shrub and Bushwhacked; the latter a chronicler of alleged misdeeds by former House majority leader Tom DeLay — are by no means unbiased judges. But they give Cheney credit where they see it as due: as an efficient secretary of defense under the first president Bush, for example, and one who concurred then that to have pursued regime change during the first Gulf War of 1991 would have invited the same disasters that have occurred in the course of the second one.

Though they shy away from psycho-history as such, the authors imply that the change in Cheney’s thinking owes much to a series of heart attacks that led him closer to the brink of death than has been publicly acknowledged. In any case, both Cheney and the government he looms so large in have clearly succumbed to an ever-hardening belief in the unbridled use of power.

As one of many clues as to who was the actual architect of our ongoing national policy, the authors conclude “[i]t wasn’t George Bush” and offer this: “The vice president’s national security staffers read all the e-mail traffic ‘in, out, and between’ the president’s [National Security Council] staffers … . Yet the president’s staff isn’t allowed to read the communication of Cheney’s staffers.” Q.E.D. And if that ain’t vice, it’s getting ominously close. — Jackson Baker

Mary Poppins, She Wrote:

The Life of P.L. Travers

By Valerie Lawson

Simon & Schuster, 384 pp., $25

In Mary Poppins, She Wrote, biographer Valerie Lawson painstakingly pieces together the life of P.L. Travers, the woman who created Mary Poppins, the much-loved nanny who blew in with the wind to save the Banks family. Careful readers of the Poppins books recognize that all was not light with the heroine, however. Poppins had an edge.

Travers too had an edge. Born in 1899, she had a tough childhood but was endlessly independent. She dabbled in acting, against her family’s wishes, and while still in her early 20s, she moved by herself from her native Australia to London to pursue a writing career. She knew Yeats and T.S. Eliot, and her close relationship with the Irish poet George Russell led her to a devotion to mysticism. She suffered from stomach problems for much of her life, most probably had lesbian affairs, and, though never married, adopted a son through odd circumstances.

The first Poppins book was published in the 1930s and was popular from the start. After years of courting by Walt Disney, Travers finally relented to a movie version, which was released in 1964 and went on to win five Academy Awards. The movie made Travers rich, but she didn’t much care for it. To Travers, Disney and his writers didn’t grasp what Poppins was all about, and, when inevitably asked for clarification, the writer was snappish and evasive.

Lawson tries to provide the context that led Travers to create the legendary Mary Poppins character. She examines Travers’ devotion to the idea of woman as nymph, mother, and crone and posits that Travers was searching for her own Mr. Banks. Mary Poppins, She Wrote is admirably exhaustive on the subject, yet what’s most striking is its tone.

Lawson doesn’t seem to like Travers, much less respect her. It begins in the preface with a defensive strike against the defensive writer’s wish for privacy.

Travers said often that she wanted her private life kept that way. But Lawson reasons that since Travers sold her papers (including personal correspondence), Travers wasn’t serious, and, in any case, Travers’ death would mean all bets were off. However, at the beginning of this project, Travers was still living. In fact, Lawson requested a meeting with her, which Travers was open to on the condition that they not talk about her but about her work. Lawson dropped the matter for 18 months before deciding to take it up again, but Travers died before they could meet. Given that Lawson first reached out to her when Travers was in her mid-90s, it didn’t occur to her that her subject wouldn’t be around much longer?

The core of Mary Poppins, She Wrote is that Travers, though not without insecurities, was strong-willed, a trait that was responsible for her success but isolated her and made her more and more irascible as the years went on. Perhaps Lawson didn’t want to deal with her and postponed serious work on the book until after Travers was gone — conveniently out of sight like Mary Poppins swept away by the wind. — Susan Ellis

Charles Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life

By Linda H. Davis

Random House, 365 pp., $29.95

If you’ve heard of Charles Addams, it’s probably because of the 1960s television sitcom The Addams Family, with its oddly lovable family of spooks — Morticia, Gomez, Lurch, Uncle Fester, Wednesday, and Pugsley. But the story behind those weird characters and their decrepit Victorian mansion goes back to 1933, when Addams, a struggling young cartoonist, managed to sell his first “drawing” to The New Yorker.

That cartoon featured a hockey player standing in his socks on the ice next to two other players. The caption: “I forgot my skates.” It’s hard to say what The New Yorker editors saw in that decidedly unfunny (at least, to a 2006 sensibility) cartoon, but it led to three other New Yorker sales for Addams that year.

Addams kept meticulous records of his sales, and author Linda Davis has written a meticulously detailed account of Addams’ eccentric and surprising life. Using apparently unfettered access to Addams’ letters, papers, and journals, she spends much of the first third of the book in a matter-of-fact recounting of the cartoonist’s childhood and his progress in making inroads at The New Yorker. One fears Davis’ style is too actuarial to compel a casual reader through these chapters, unless they have a prior interest in Addams. The early chapters are a dry slog, for the most part.

But things get more interesting as Addams’ life gets more complex. He was an odd-looking fellow, with a large bulbous nose and slicked-back hair, but he became a bon vivant who moved in high society — a lover of fast cars, fine cigars, and beautiful women (including Joan Fontaine, Greta Garbo, and Jacqueline Kennedy). But it was a woman with the rather odd name of Barbara Barb who most impacted Addams’ life. She looked like a “bimbo” and she looked like Morticia — and she was a lawyer: a lethal combo that gave Addams all he could handle for many years.

Charles Addams becomes an interesting read after Davis warms to her subject in the middle section of the book. Or perhaps it’s that Addams just becomes more interesting. Either way, it’s a life worth reading about.

— Bruce VanWyngarden

House of Hilton:

From Conrad to Paris: A Drama of Wealth, Power, and Privilege

By Jerry Oppenheimer

Crown, 277 pp., $24.95

It was the sex tape that spawned an empire. A Night in Paris took this generation’s foremost celebutante and turned her — however improbably — into a marketable brand for perfume, video games, books, and television programs.

Or so says Jerry Oppenheimer, author of Front Row: Anna Wintour, Just Desserts: Martha Stewart, The Other Mrs. Kennedy, and now House of Hilton. In it, Oppenheimer tries to solve the riddle of how a woman like Paris came into being.

The answer is part ambition and drive, part greed and gold-digging. The main hypothesis in Oppenheimer’s tell-all — if a book about Paris Hilton can be said to have a hypothesis — is that Paris is a product of her lineage. From Conrad Hilton, the hotel magnate who started his empire with a flophouse in Amarillo, Texas, Paris got her eye for opportunity and her reputed business acumen. From her mother, Kathy, and her grandmother, Big Kathy, she got her appetite for stardom.

In this breathless, Enquirer-like look at the Hilton clan, Oppenheimer portrays a family tree rife with bad seeds. Big Kathy is a “stage mother from hell” who tells her daughters to marry rich. Paris’ parents, Rick and Kathy, are opportunists who party all the time and exploit the Hilton name for discounted hotel rooms and apartments, comp’ed food and drink, and even free babysitting at hotels around the world. And beginning with Conrad Sr. — who married Zsa Zsa Gabor in 1942 and then divorced her in 1946 — the Hilton men appear to have had an eye for the ladies — the younger, the better. (And Conrad [Nick] Jr.?: His marriage to Elizabeth Taylor in 1950 lasted 205 days.)

Despite her behavior and the behavior of the rest of her family, Oppenheimer contends that the success Paris has created should be respected. Despite their many flaws, both Conrad and his son Barron (Paris’ grandfather) believed their children should make their own way in the world. Paris is rich, but her father is one of eight children and she’s one of four, so she isn’t in line for a big inheritance. “No doubt Paris’s great-grandfather would be extremely proud of the Hilton entrepreneurial spirit that Paris had inherited and was aggressively exhibiting,” Oppenheimer writes. And though she has her detractors, her products — albums, movies, perfume — sell. As Paris has declared, “I’m laughing all the way to the bank.”

I guess the joke is on us.

— Mary Cashiola

The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game

By Michael Lewis

Norton, 299 pp., $24.95

Quarterback insurance. That’s what football coaches and scouts call men who play left tackle on the offensive line. For a right-handed quarterback dropping back to pass, a left tackle protects his blind side. Which is why the finest left tackles earn more money in today’s NFL than any position other than quarterback.

In his aptly titled The Blind Side, Michael Lewis — best-selling author of Moneyball — chronicles the discovery and gridiron development of Michael Oher, a hulk of a young man (6’5″ and 350 pounds as a high school junior) who finds that his one way out of an impoverished, dead-end youth is the potential he embodies for greatness as an NFL left tackle.

The son of an alcoholic mother and a father he barely knew (and who died violently), Oher transfers from Memphis’ Westwood High to the private Briarcrest Christian School after his freshman year but only after capturing the eye of BCS football coach Hugh Freeze. An African American, Oher is exposed to a world of affluence and academia he would have never seen without the care of Sean Tuohy, a former basketball star at Ole Miss (and current TV analyst for the Memphis Grizzlies), who has a daughter at Briarcrest and eventually adopts Oher as his son. Tuohy’s role in steering Oher’s academic development is critical to whatever college future his adopted son might have. As for the means? Writes Lewis, “One of the lessons [Tuohy] had picked up from his own career as an NCAA student-athlete was that good enough grades were available to anyone who bothered to exploit the loopholes.”

Oher’s overnight stardom is so astonishing it’s troubling. Having never played organized football until his junior year at Briarcrest, Oher receives scholarship offers from, according to Lewis, every major college program except Penn State. He decides to attend Ole Miss, where he’s now a sophomore and Freeze is an assistant to head coach Ed Orgeron.

Lewis is a fine story-teller, and his venture into the game of football includes a nice history lesson on the passing game. It’s the creative minds behind modern football that give the book its subtitle: “Evolution of a Game.” During the 1980s, protecting a football team’s most valuable instrument — its quarterback — took on a new premium as pass-rushing monsters like the New York Giants’ Lawrence Taylor were winning games by themselves. When free agency arrived in 1993 and opened the salary structure for players who didn’t pass the ball (or rush the passer) for a living, the market for talented left tackles blew the lid off preconceived notions of a lineman’s value. This is insider football, and a reader not familiar with the game’s positional nuances may be turned off by chapters devoted to such. But this “evolution” is precisely why a teenage behemoth from the Memphis slums is worth a book.

The Blind Side isn’t so much a human-interest story as it is a tale of football interest. And it’s the confluence of lives — and interests — around Michael Oher that gives the tale its weight. A boy giant — seemingly born to block — finds himself behind his own “blockers” intent on clearing the way to pro football and unlimited wealth. About the only question left would seem to be who has Michael Oher’s blind side?

— Frank Murtaugh

Sloth

By Gilbert Hernandez

Vertigo, 128 pp., $19.99

Gilbert Hernandez’ Sloth presents two seemingly parallel stories about teens Miguel, Lita, and Romeo, and those stories turn on the myth of a satyr and a lemon orchard.

The book opens as Miguel has just woken up from a one-year coma. Upon waking, Miguel is healthy but left with the need to slow everything down: his gait, his speech, his lovemaking, the songs his band plays.

Miguel also reconnects with girlfriend Lita and bandmate Romeo — who may or may not rival Miguel for Lita’s affections.

Miguel has had recurring dreams for years about lemons raining down from the sky, prompting him to hope that “dreams are dreams and don’t have anything to do with reality.” After the trio investigates the urban legend of the lemon orchard’s Goatman, events unfold that prove his hopes wrong.

Hernandez is best known for his long-running serial Love & Rockets. His Palomar stories in that series are just about the best thing ever created in the comic-book medium. Amazingly, Sloth is Hernandez’ first original graphic novel.

Hernandez possibly is better than any writer at capturing the tenebrous years between childhood and adulthood. (One challenger to that claim is his Love & Rockets co-writing brother, Jaime.) In Sloth, teens are challenged by pain, loneliness, and an aching to connect, but they are also empowered by courage, joy, loyalty, and supernatural levels of willpower.

Hernandez’ cartoon art is equally excellent. His pen captures faces with a few deft details, and in the faces of adults, you can see the youngsters they once were. It reinforces a common theme in Hernandez’ stories: You can’t escape your childhood. Perhaps that’s why Hernandez is so fascinated by it.

With Sloth, Hernandez has added to what is already a spectacular body of work. It’s further evidence that he’s one of the most exciting and entertaining voices in the field of graphic novels.

— Greg Akers

33 1/3 Greatest Hits, Volume 1

Edited by David Barker

Continuum, 264 pp., $14.95 (paper)

Like most best-of compilations, 33 1/3 Greatest Hits, Volume 1 is only a partial portrait of a larger subject, in this case Continuum’s popular series that features writers from different backgrounds extolling the virtues of their favorite albums. The series’ greatest virtue is its breadth: Contributors include academics, critics, and musicians, who expound on rock, pop, funk, hip-hop, soul, folk, dance, alternative, and Prince. Admirably, editor David Barker dictates no approach to the albums, allowing the writers to consider the music academically, historically, or autobiographically. The result is a diverse and multifaceted series that covers not just the range of popular music but the gamut of pop-music criticism.

Excerpting chapters from the first 20 installments, 33 1/3 Greatest Hits ably showcases this essential variety. Musicians tend to reminisce: Colin Meloy of the Decemberists describes the teenage thrill of hearing the Replacements on his transistor radio, and Joe Pernice’s take on the Smiths’ Meat Is Murder, which recalls a teen suicide that shocked his Massachusetts suburb, barely touches on the album at all, yet feels strangely relevant.

Not every author features himself so prominently. Andrew Hultkrans’ detailed exegesis of Love’s Forever Changes touches on Arthur Lee’s paranoia but only hints that it mirrors Hultkrans’ own. Best is Warren Zanes’ string of anecdotes on interviewing Jerry Wexler about Dusty in Memphis, which at first reads like mere digressions but adds up to an important explication of the power of Southern music in the 1960s.

The diversity that makes 33 1/3 Greatest Hits such an intriguing series also means a listener won’t agree with every approach. The autobiographical chapters often leave no room to discuss the workings of the music, and the more academic approaches sometimes lapse into dry exposition.

The excerpts assembled here, unlike the songs that populate greatest-hits albums, weren’t written to be collected, and this compilation can be frustrating. Just when you start getting into a chapter, it ends. And there are no introductions or writer bios to contextualize the selections. 33 1/3 Greatest Hits is nevertheless a useful introduction to contemporary rock writing, revealing a discipline as diverse as its subject. It is, however, no substitute for the complete series. — Stephen Deusner