Too Much Happiness

By Alice Munro

Knopf, 320 pp., $25.95

Alice Munro, acclaimed

Canadian writer and recipient of the 2009 Man Booker International

Prize, has delivered something dark and exquisite with her new

collection of short stories, Too Much Happiness. In it, Munro

continues to explore the complexities of relationships and

self-awareness, all with a precision and shrewdness about the worlds

she creates. Each story reads smoothly, even as it sometimes tears at

something violent and disturbing.

From the opening story, the collection has an air of tragedy: A

woman loses her three children in unusual circumstances and is faced

with an unthinkable emotional dilemma. Then: A recently widowed woman

takes on a surprising role to save herself from an intruder. A dying

man is the object of conflicting desires. An estranged son betrays the

shortcomings of a marriage. A woman recalls a shocking and sinister act

she committed as a child.

Munro has spent a lifetime writing short stories, which explains her

mastery of the genre where her forceful simplicity reigns supreme. But

she seems to be aware of how the genre is sometimes perceived —

as a stepping stone to the longer form (and greater art?) of the novel.

In one humorously self-referential moment, one of her characters

says:

“[It] is a collection of short stories, not a novel. This in and of

itself is a disappointment. It seems to diminish the book’s authority,

making the author seem like somebody who is hanging on the gates of

Literature rather than safely settled inside.”

Perhaps here Munro is only proving her vast ability to write from

multiple, even opposing viewpoints. Her stories cover eras and

countries. They take on genders and generations. They give voice to a

betrayer and the betrayed. For these reasons, and for many others,

Alice Munro has secured herself a place inside those gates. —

Hannah Sayle

The Humbling

By Philip Roth

Houghton Mifflin, 160 pp., $22

The protagonist of The Humbling, Philip Roth’s latest book,

is Simon Axler, an aging stage actor who has lost the trick of being

someone else. It’s not exactly stage fright that has him frozen and

fearful; it’s an inability to believe in the process of acting,

illusion. He cannot escape Simon Axler.

Left to himself (after a stay in a sanitarium and after his wife has

left him), Axler moves to a secluded house to end his days in

isolation. But he can’t escape his self-absorption and it turns into

poison, so much so that he is contemplating the ultimate exit: suicide.

Into this solitude comes the daughter of old friends, a lesbian college

teacher named Pegeen. An unlikely affair blossoms between them,

temporarily staving off Axler’s darker imaginings.

Roth’s writing here has a wildness to it, as if he’s writing in a

fever. Perhaps Roth himself feels that way. The Humbling is a

meditation on mortality, and as with all of Roth’s writing, he is

fearless, even in the face of the final question. Roth tears at his

themes with unblinking honesty and stripped-down prose. Perhaps Roth,

now 76, is writing according to his own sensibility. Gone are the

bed-hopping miscreants of his earlier novels, replaced here by an

introspective older protagonist, who is staring into the abyss.

Not to say that Roth eschews the sexual element. Axler does okay for

a man who considers himself dried up. Roth has always plumbed the

carnal side of his characters, and, like Updike, he does so with

unflinching frankness. But Roth also treats his protagonist here with

empathy and authenticity.

Readers of Roth understand that he takes risks other writers

circumvent. It is this daring that defines Roth and places him in the

front ranks of the novelists of our time. — Corey

Mesler

It’s a Gift

Like the story it’s based on, Joel Priddy’s new

graphic adaptation of The Gift of the Magi

(It Books/HarperCollins, $14.99) is deceptively

simple. You may well remember the O. Henry

tale from grade school: Christmastime, a married

couple struggles with what to gift each other on

such mean savings and wind up exchanging presents that are

ironically and heartbreakingly inappropriate. But it’s the loving

thought that counts. Cut, print, preserve.

Not so fast. Priddy — who teaches illustration and cartooning

at the Memphis College of Art — revivifies the chestnut and finds

in it volumes of wordless charm. The cartoonist emphasizes the emotions

of each moment, in each panel, suffusing them with such meaning that

the gotcha ending becomes less a startling plot point and more a

symbolic embodiment of the couple’s love.

Priddy packs a punch. The visual centerpiece is luxurious golden

hair flowing across several pages — a lively illustrative

presence like one of Beto Hernandez’s skies.

The Gift of the Magi can be bought separately or as a

stocking-sized holiday gift set with an illustrated version of Hans

Christian Andersen’s The Fir-Tree (adapted by Lilli

Carré) and L. Frank Baum’s A Kidnapped Santa Claus

(adapted by Alex Robinson), also from It Books. — Greg

Akers

Wolf Hall

By Hilary Mantel

Henry Holt, 560 pp., $27

Hilary Mantel was amazed when she won the 2009 Man Booker Prize. Her

Wolf Hall was a critics’ favorite. “They say the favorite never

wins,” she explained to me by e-mail, but Wolf Hall was favored

for a reason: A good man is hard to find.

That man is Thomas Cromwell, born in Tudor London, a commoner whose

rush to power makes a king, Henry VIII, declare him Earl of Essex. As

Henry’s chief adviser, Cromwell boasts a usefulness that never keeps

his hands quite clean enough for courtiers.

This novel, Mantel’s 10th, is peopled with historical figures: Ann

Boleyn, Thomas Cranmer, Thomas More. It shows us Cromwell’s rise to

stand among them. Historically, Cromwell led a public life where

secrets die crying, but fiction fills the gaps. Mantel writes of “the

intimacies of politics” that muscle a blacksmith’s son to a king’s

can-man. You want the world? Cromwell delivers and asks, “What

color?”

A buoyant wit lures us into Cromwell’s domain. Thanks to Mantel, we

come to know a living being. As the author said last year of Wolf

Hall, “There’s a man in there!”

Watch him skirt the fall of his first master, Cardinal Wolsey, with

an ease that aims him where Wolf Hall ends. Mantel leaves her

man some five years shy of his end: an ax on July 28, 1540. “So now I

have the next one to write, you see,” Mantel says.

Cromwell’s climb from soot to king’s supper is Wolf Hall. His

tumble from the Tower is in the offing. Know the outcome? No matter.

Mantel specializes in resurrection.

I met Hilary Mantel on the subject of Robespierre on a 28th of July,

the date Robespierre’s head fell in 1794. But that’s the stuff of

synchronicity, other stories. For the present, crack Wolf Hall.

Cromwell’s in there. He wants out.

— Alice Long

Hungry?

By 1974, Ruth Lockwood had logged a dozen years producing The

French Chef for WGBH in Boston, working alongside Julia Child, the

show’s unflappable host. Despite a hectic schedule — sometimes

taping four shows a week — Lockwood said Child never lost her

temper. Except once. A dish towel and pot holder caught fire on the

set, and the cameramen stopped shooting. Child was furious. She wanted

the mishap filmed to show viewers what to do if the same thing happened

at home.

Lockwood’s story is one anecdote among many in an article by Calvin

Tomkins first published 35 years ago and reprinted in a remarkable

collection of food writing from The New Yorker called Secret

Ingredients (Modern Library, $18). Edited by David Remnick, the

magazine’s editor today, the tell-alls, essays, memoirs, cartoons, and

short stories are a welcome reminder that Americans were passionate

about food and drink long before reality television.

At The New Yorker, distinguished food writers have helped

steer the magazine’s content throughout its history, beginning in 1935

with A.J. Liebling, who in his essay “A Good Appetite” wrote, “Each day

brings only two opportunities for field work, and they are not to be

wasted minimizing the intake of cholesterol.”

In all, more than 50 contributions make up this celebration of

writing and food. Some stories are poetic, like M.F.K. Fisher’s lament

(in “Secret Ingredient”) for the “witches of yesterday” who zealously

guard their favorite recipes. Other pieces are rich with conversation

and memory, like John McPhee’s portrait of forager Euell Gibbons, one

of the fathers of the natural foods movement.

“What the editors who created The New Yorker understood is

that a magazine travels not only with its mind but also, like an army,

on its stomach,” Remnick writes in his introduction to Secret

Ingredients, an evaluation applicable, as well, to the lucky

readers who discover this book, first published a couple years ago but

issued in paperback in November. — Pamela Denney

Last Night in Twisted River

By John Irving

Random House, 554 pp., $28

John Irving is up to much more than remarkable storytelling in his

12th novel, Last Night in Twisted River. In a seeming effort to

tease those eager to read autobiographical synergy into his fiction,

Irving goes one further.

The novel distills the author’s previous themes and motifs (bears,

death, missing limbs, sex with older women, tragedy and hope);

demonstrates his usual acrobatic performance with syntax and grammar

(there are actual discussions about the semicolon); displays his sheer

mastery of timing (the tantalizing dropped detail leading provocatively

to a full-blown narrative); and chronicles his own education and

literary craft — even the order of his novels — through one

of three central characters: the “famous writer” Daniel Baciagalupo

(nom de plume: Danny Angel).

Danny, whose father Dominic begins his career in a New Hampshire

logging camp, is baptized as a writer not by his beloved but

short-spoken father but by a profanity-spewing, maniacal logger named

Ketchum whose stories capture the young boy’s imagination and whose

love proves as powerful as the man himself.

One night in the cookhouse on Twisted River, Danny, age 12, mistakes

the cook’s lover for a bear and kills her, thus setting father and son

in motion. Under the guidance of Ketchum, the two begin a series of

moves hoping to stay ahead of the murdered woman’s boyfriend, a New

Hampshire sheriff more heinous than any criminal.

Thankfully, Irving’s humor provides a cushion for the tragedies

stalking the characters. “The Cook,” Irving writes, “had an aura of

controlled apprehension about him, as if he routinely anticipated the

most unforeseen disasters.”

The death of a beloved child — Twisted River has two

— answers Dominic’s trepidation. Irving commented tellingly in a

recent interview, “I’m in terror of losing a child. It’s never happened

to me, but I am clearly compelled to write about it over and over

again, and in a way I think, psychologically at least, this says more

about me autobiographically as a novelist than the fact that Danny

Angel goes to the Iowa Writers Workshop and has Kurt Vonnegut as a

teacher, which I also did.”

As Dominic insists, “There were not enough bends in Twisted River to

account for the river’s name.” The same cannot be said of this abundant

novel where Irving accepts his characters’ obsessive fears of loss and

loneliness while granting them warm-hearted appreciation for lives

fully lived. — Lisa C. Hickman

Strength In What Remains

By Tracy Kidder

Random House, 304 pp., $26

Strength in What Remains, by Tracy Kidder, is the true story

of not only what happens during a genocide but what it takes to survive

one.

Deo was a medical student doing an internship in rural Burundi in

1993 when civil war broke out. The Hutu president had been

assassinated, and in retaliation, Hutu countrymen began killing Tutsis.

Deo escaped being massacred by a Hutu militia and, keeping away from

the roads, made his way to Rwanda and a refugee camp. A few months

later, however, the same racial violence erupted in Rwanda, sending Deo

fleeing back into Burundi.

Neither place was safe, and a friend from medical school helped him

get to New York, where he arrived alone, with $200 in his pocket and

knowing no English.

With hard work, perseverance, and a little luck/fate/divine

intervention, Deo went from sleeping in New York’s Central Park to

taking classes at Columbia University. His goal: to become a doctor and

build a clinic in his village in Burundi.

Whereas accounts of genocide can sometimes blend into an

overwhelming wave of numbers and atrocities, the focus of this account

on a single individual makes it all the more heartbreaking. At

Columbia, for example, Deo takes philosophy classes to try to

understand how neighbors could kill neighbors, priests their

parishioners, and teachers their students.

This gripping book examines roughly the same question. The first

half is told from Deo’s point of view as he experienced it. The second

half includes interviews with the people who helped him and with an

older Deo.

There are no answers in genocide, but Deo’s story shows there are

ways to create peace. I never wanted to put the book down. —

Mary Cashiola

Blues & Chaos: The Music Writing of Robert Palmer

Edited by Anthony DeCurtis

Scribner, 452 pp., $30

Author of Deep Blues and indispensable histories of the

Rolling Stones and Jerry Lee Lewis, Robert Palmer is a complex and

contradictory figure in music criticism. As a Southerner, he grew up

the only white kid at soul and R&B shows in Little Rock; as a

musician, he jammed with Ornette Coleman, U2, and the Master Musicians

of Jajouka; and as a functioning junkie, he developed a habit that

would hasten his death in 1997.

Those facets contributed to his writing, in which he sought out the

sincere, the passionate, and the transcendent in a range of musical

styles and traditions. Palmer emerges as irascibly opinionated,

obsessively fascinated, yet soberly matter-of-fact in this new

collection of interviews, articles, reviews, profiles, and other short

pieces.

The breadth of genres and artists covered in Blues &

Chaos can be astonishing. He humanizes Ray Charles, Jerry Lee

Lewis, and Muddy Waters, albeit with subtle fawning in his prose. He

engages more closely and critically with artists of his own and

subsequent generations, including the Band, Eric Clapton, Elvis

Costello, and, in particular, John Lennon.

Despite its shortcomings, Blues & Chaos refuses to gloss

over Palmer’s faults but instead portrays him as a man with deep blues

of his own.

— Stephen Deusner

The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorized History

By John Ortved

Faber & Faber, 352 pp., $27

John Ortved’s The Simpsons has a few things in common with the

animated series whose story it tells. It begins as a risky curiosity

that may or may not fly, grows into an engaging soap opera, then wears

out its welcome long before there’s any end in sight.

Ortved’s oral history of television’s longest-running animated

series is emphatically historical. It’s not a lesson in comedy writing

or an insider’s guide to making a hit TV show, and it’s never

particularly funny. The cast of characters, however, ranges from media

mogul Rupert Murdoch to Deborah Groening, the ambitious ex-wife of

Simpsons creator Matt Groening, and they are every bit as

over-the-top as the inhabitants of Springfield.

“Rupert Mudoch, Barry Diller, Mad magazine, Saturday Night

Live, Fox, and Bill Cosby all had a hand in making The

Simpsons,” Ortved wrties. “As did all the crappy sitcoms it was

responding to, as well as the conservative culture that produced

them.”

The Simpsons history offers plenty of trivia for fans. But

Ortved is at his best when he channels the spirit of his subject

matter: “We thought we were writing these really funny, smart, special

shows,” writer/producer Jay Kogen is quoted as saying. “And then

someone showed us this study Fox had done. The number-one reason people

liked The Simpsons was ‘all the pretty colors’ and they liked it

when Homer hit his head.” — Chris Davis

The Simple Little Vegan Dog Book: Cruelty-Free Recipes for

Canines

By Michelle A. Rivera

Book Publishing Company, 80 pp., $9.95 (paper)

As a vegan, I avoid meat, eggs, and dairy. I don’t wear leather,

silk, or wool. So you can imagine the conflict I face every day as I

feed my dog and six cats pet food made from ground, processed meat.

Although commercial vegan pet food is available, it’s out of my price

range.

Enter The Simple Little Vegan Dog Book by Michelle A. Rivera,

a cute volume of homemade entrées, biscuits, and

special-occasion treats for canines. According to Rivera, dogs, like

humans, are omnivores and can get their nutrients from meatless

meals.

My dog Datsun certainly didn’t miss the meat in Snoopy’s Great

Pumpkin, Rice, and Beans (canned pumpkin, brown rice, and red beans),

and he begged for more Barking Barley and Wheat Surprise (a casserole

of lentils, barley, and whole-wheat flour). Each night, I reward him

with a homemade Yeasted Gourmet Dog Treat, cut into bone shapes using a

cookie cutter.

Rivera explains that most commercial dog foods are loaded with

slaughterhouse byproducts and “4D meat (meat from animals that are

dead, diseased, dying, or disabled).” It’s meat unfit for human

consumption, so she argues that we shouldn’t pollute our pet’s health

with leftover scraps.

Rivera also provides succinct lists of which plant foods are

beneficial to dogs (like pumpkin and beans) and which ones they should

avoid (like chocolate and onions). As for cats, Rivera warns against

switching them to a meat-free diet. As obligate carnivores, she says

felines aren’t able to get the proper amount of taurine from a vegan

diet.

Although I’m not comfortable switching Datsun over to a full-on

vegan diet yet, I’ve begun supplementing one of his two daily meals

with a home-cooked vegan dinner from Rivera’s book. The best part?

Since his meals are totally vegan, we can share. — Bianca

Phillips

Odds/Ends: Xmas ’09 Edition

In this age of the Kindle (1 and 2) — and the Sony Reader and

the Nook and the forthcoming QUE — you remember that printed

product with pages that you not only sit with and think through but

dog-ear and mark the hell out of: books. And yes, they’re still making

them — in record numbers (the more crowd-pleasing the author

writing them, the bigger the number printed of them) but at a price

— a crazy-low price thanks to big-boxer Walmart and competitive

online retailers.

The alternative: Screw it. Don’t download the book. Support your

bookseller. And see here if it’s bookish ideas you need this Christmas

and if the person on the receiving end is the literary, arty type.

Caution: The following come with a price.

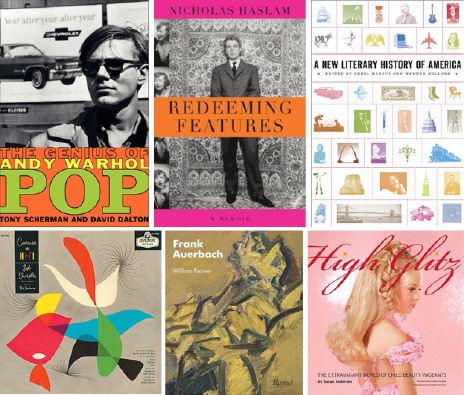

For that literary person on your list: A New Literary History of

America (Belknap Press/Harvard University Press). It’s got Greil

Marcus (hipster central) as an editor. It’s a thousand-plus pages. It’s

$49.95. And it’s alternative. How alternative? There’s an entry for the

National Football League. Sylvia Plath? Not so much.

Pop: the ’60s art movement that will not die. And how could it with

Warhol dead for decades but still inspiring every rising generation of

art kids who are 1) fed up with American commercialism but 2) ready to

cash in on American commercialism. See then: Pop: The Genius of Andy

Warhol (HarperCollins) by Tony Scherman and David Dalton, for $40.

Tony Shafrazi is crazy about this book. You don’t know who Tony

Shafrazi is? Never mind.

Weird: beauty pageants. Real weird: child beauty pageants. Simon

Doonan, a celebrated window dresser, is ga-ga — about child

beauty pageants. So ga-ga about them that he’s written the foreword to

High Glitz (powerHouse Books, $49.95) by Susan Anderson. Is this

the same Susan Anderson who authored Porn for New Moms and

Itty-Bitty Toys: How To Knit Animals, Dolls, and Other Playthings

for Kids?

Weirder still: the life of Nicky Haslam, and he writes of it in

Redeeming Features (Knopf, $30). Claim to fame? Among a ton of

other unessential stuff (including partying and decorating): sex with

Lord Snowden (before Snowden married Princess Margaret), and in the

’90s, he surgically reconstructed himself to look like a biker

(rough-trade division). BFFs include: Mick Jagger and painter Lucien

Freud, who’s a friend of …

Frank Auerbach, the English painter with paintings so dense with

paint the paint has trouble staying on the canvas. Doesn’t matter.

Auerbach’s a rarity: a great artist in the great tradition of English

portrait painting. He’s now, finally, really getting his due. The

book’s called Frank Auerbach (Rizzoli) by William Feaver. But

it’ll set you back 150 bucks.

That’s nothing. The limited-edition, signed, custom-slipcased

Alex Steinweiss: Creator of the Modern Album Cover (Taschen)?

It’s a whopping $500. Steinweiss’ album covers, beginning in the ’40s

and covering three decades? They were back then, they still are: the

locus classicus of “cool.” — Leonard Gill