Long, Last, Happy: New and Selected Stories

By Barry Hannah

Grove Press, 459 pp., $27.50

“This is why I tell this story and will never tell another.”

That simple line provides a devastating conclusion to “Testimony of Pilot,” one of Barry Hannah’s best and most popular short stories, a tale of marching bands, test pilots, and confounding tragedy. But it could cap any of his stories. He wrote each one as if it might be his last, as if his life depended on it — a tone that lends them all a momentousness and majesty.

Hannah, who taught creative writing at the University of Mississippi, always has been revered as a prose stylist and rightly so: He dotted his sentences with Southern colloquialisms and made-up phrases brimming with insight, writing them as models of concision and cleverness. Spanning nearly half a century, Long, Last, Happy, however, argues for him as storyteller first and foremost. Hannah rejected the traditional story arc in favor of just hanging out with his characters for a few pages, peeking into their lives and recording what he saw. Full of flights of immense fancy yet strongly grounded in character, these are stories about men at their loosest ends, hounded by bad-luck streaks, cursed by impossible loves, caught up in improbable wars. And fishing: What Nabokov did for butterflies, Hannah does for bass.

The men who populate these stories tend toward a certain type, yet Hannah makes them unique individuals, teasing out their quirks, their fears, and their humanity.

“I have become the scribe,” says the unnamed narrator of “Bats Out of Hell Division,” “not voluntarily, but because all my limbs are gone except my writing arm.” His regiment is all but defeated, yet the soldier rushes, via wheelbarrow, into battle anyway, searching for the bullet that will end his life and literary duties. It’s a strange, warped story but a reminder that Hannah himself was all writing arm.

Organized chronologically, Long, Last, Happy is bookended by stories that will be new to even diehard Hannah readers. The earliest, “Trek,” originally appeared in his college literary magazine. Obscure yet aggressively engaging, it shows a precocious talent finding his voice and embracing his own deviant mannerisms. The final story, “Rangoon Green,” one of four never-before-published stories in this volume, is a harrowing account of the second Gulf War told from a soldier’s point of view. Everything in between these two stories shows how Hannah’s idiosyncratic style developed over the years, how it grew more streamlined without relinquishing its eccentricities, how he devised an odd, personal morality embedded in the conflicts of Southern life.

Hannah died earlier this year, leaving four short-story collections and a handful of novels. Surely there are more posthumous volumes to come — new editions of out-of-print titles (such as Captain Maximus, excerpted here), unfinished pieces, assorted writings. Long, Last, Happy, as immersive and exciting as it is, is no substitute for his previous collections — more like a complement to them. There is hard life and soul in these stories, and it’s sad that Barry Hannah will never write another. — Stephen M. Deusner

The Life and Opinions of Maf the Dog, and of His Friend Marilyn Monroe

By Andrew O’Hagan

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 288 pp., $24

A word of advice: You might not want to mention that you are reading a book about Marilyn Monroe written from the viewpoint of her Maltese, Mafia Honey. To do so will elicit blank stares, guffaws, and are-you-kiddings.

However, as the title suggests, that is precisely what The Life and Opinions of Maf the Dog, and of His Friend Marilyn Monroe is. And given the premise of the book, it’s perhaps a testament to author Andrew O’Hagan’s talent — his books have been awarded the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, and the E.M. Forster Award — that it is being taken seriously at all.

In 1960, Frank Sinatra gave Marilyn Monroe, fresh off her breakup with playwright Arthur Miller, a Maltese poodle. In the book, the dog has several brushes with celebrity prior to Marilyn — living first with painters Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, then Natalie Wood’s parents — before being scooped up by Sinatra. And that may have been the case in real life too, except that O’Hagan’s skillfully crafted prose and dialogue read more like fiction than nonfiction … but the narrator is, of course, a dog.

Maf (for short) goes to nightclubs, psychotherapy, and the Actors Studio with his “fated companion.” O’Hagan handily gets around the point-of-view problem of his four-legged narrator by allowing dogs to have such good ears that they can “hear” human thought and emotion. (The learned pup also has a working knowledge of politics, Proust, Plato, and poetry. Among other things.)

Unfortunately, it wasn’t a world that held my interest as firmly as I’d have liked. And though O’Hagan’s novel presents a flawed Marilyn, there is also something star-struck as well, as in:

“Every creature is an effusion of something rare, but she was beyond reach at the centre of her ghostly aura, the night crowding around her as she sang ‘Happy Birthday’. My fated companion looked as if nothing real had ever touched her, no small regret, no other person.” — Mary Cashiola

My Prizes: An Accounting

By Thomas Bernhard

Knopf, 144 pp., $22

You must be a person of considerable gifts for an accounting of your accolades to be interesting or even, quite frankly, tolerable. Thomas Bernhard is such a person. Praised as one of the greatest Austrian writers of the 20th century and simultaneously scorned as a Nestbeschmutzer by the Austrian press (a Nestbeschmutzer is “one who fouls his own nest” — in this case, Austria and the literary establishment), Bernhard harnesses the right mix of literary genius and enfant terrible to make this book a biting but ultimately humble work.

The short essays are about more than the prizes Bernhard won over his storied career; they detail how each prize affected him, often in unexpected ways. To accept the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna, he bought a new suit and, with his aunt, traipsed off to the ceremony — only to be overlooked for a time as a member of the audience. With the money from the Literature Prize of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, he bought a fog-covered house he couldn’t afford and could barely see to inspect. And with the money from the Julius Campe Prize, he bought a sparkling white car with red interior, which later hurtled him into the path of an oncoming vehicle and nearly cost him his life.

Certainly Bernhard is moved by some of the prizes he’s won. The Campe Prize from Hamburg is particularly important to him. But having served on a board for determining literary prize-winners, he sees how arbitrary the process can be and, at times, how a prize can be as much a slap in the face as a cause for celebration. (“Now I had to go to this very Ministry and allow these very people to hang a prize on me when I heartily despised both them and it.”)

And so, spurning the pretensions of the literary industry, which so often take precedence over the artist and the work at hand, Thomas Bernhard catalogs the prizes by their monetary value and outcome. Happily, they’re the makings of good stories. — Hannah Sayle

I Found This Funny: My Favorite Pieces of Humor

and Some That May Not Be Funny At All

Edited by Judd Apatow

McSweeney’s Books, 476 pp., $25

After a long love affair with novels, we’ve had something of a renaissance of short stories in the past decade or so, ushered in by collections edited by prominent people and organizations. The short story is the most noncommittal version of literary prose, and if you trust the editor, chances are you’ll find a few new authors to put on your reading list. Lucky for us, McSweeney’s head honcho Dave Eggers finally asked himself: Who better to recommend a few pieces of humor than the king of short attention spans, filmmaker Judd Apatow?

Apatow (writer and director of Knocked Up and The 40-Year-Old Virgin) says upfront that the pieces in I Found This Funny are not all funny, per se; some, like Miranda July’s “Majesty,” are dark and poignant with a side of hilarity. These appear with highlights from the arbiters of modern comedy — Steve Martin, Jon Stewart, Adam Sandler, Conan O’Brien — backed by Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Flannery O’Connor. It’s less a selection compiled to make you laugh out loud than the story of how Apatow’s brand of humor developed, punctuated by his own heart-wrenching account of working on Freaks and Geeks, the prematurely canceled television series that began his career (and introduced him to Seth Rogen and James Franco).

I Found This Funny is refreshing because these collections often come from inside the literary world and end up containing the requisite pieces from big literary names and not much else.

Apatow branches out, including screenplays, essays, borderline-crude comics, and a faux lawsuit between Wile E. Coyote and the ACME company. Here we have a compilation of good work, quickly digested but held onto by someone without much time or impulse to be thorough, who says earnestly that reading more made him a better writer, that the honesty of Dave Eggers (A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, What Is the What) filtered into his movies and made him want to share that feeling with people who care about those films. — Halley Johnson

Proceeds from the sale of I Found This Funny go to 826 National, a nonprofit tutoring, writing, and publishing organization with locations in eight cities across the U.S.

Whiter Shades of Pale: The Stuff White People Like, Coast to Coast, from Seattle’s Sweaters to Maine’s Microbrews

By Christian Lander

Random House, 240 pp., $15 (paper)

White people are funny, and according to Christian Lander, the most hilarious type of white person is the left-wing, starry-eyed North American. Lander’s second book, Whiter Shades of Pale, based on his popular blog “Stuff White People Like,” includes diagrams of trendy white folk according to their city of choice alongside musings on white behavior.

As a white person, not to mention one with a liberal arts degree, I personally can attest to, first-hand or through other goofy white people, everything Lander touches on. From the collective comfort of My So-Called Life to a penchant for photography and girls with bangs, Whiter Shades of Pale is spot-on satire, so long as your target is white people who happen to be affluent and socially conscious. People who fall outside of these categories are lovingly referred to by Lander as “the wrong kind of white people,” which mirrors the judgmental attitude ingrained in an affluent, socially conscious white person’s mindset.

Pinpointing terminally hip cities and the white people who love them makes this follow-up to Stuff White People Like: A Definitive Guide to the Unique Taste of Millions a veritable road trip (another favorite pastime of white people). As a white Canadian, Lander has the inside scoop, exploiting the psyche of white people, including their crippling fear of weight gain and their inexplicable enthusiasm for expensive things made to look cheap. He also addresses specific TV shows, movies, clothing, and Bob Marley as keys to understanding the white person’s experience.

Lander’s text is geared toward all types of people and provides them with invaluable pointers on interacting with white people. But anyone with a sense of humor can appreciate this book and the hypocrisies unknowing white people exhibit each and every day. — Ashley Johnston

Death of the Liberal Class

By Chris Hedges

Nation Books, 248 pp., $24.95

A trivia question for an enlightened bunch of head-gamers might be: What epigraph appears at the beginning of the Academy Award-winning film about a mine-sweeping unit in Iraq, The Hurt Locker, and who said or wrote it? The answer is: “The rush of battle is often a potent and lethal addiction, for war is a drug,” and the author of those words is Chris Hedges, former war correspondent for The New York Times. The quote appeared originally in Hedges’ book War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning.

Hedges’ very titles have a way of reading like developed thesis statements, and the title of his newest work, Death of the Liberal Class, speaks for itself as well. In this book, Hedges delivers a scathing and unrelenting critique of what he sees as contemporary America’s corporate-controlled, militarized, consumer-oriented culture, and the chief villains are not the oligarchs in charge, as one might expect, but the thoroughly co-opted members of a now-fossilized “liberal class” who seek practical ends for themselves rather than moral results for society. They are, in Hedges’ view, little more than window-dressing for the prevailing corruption.

It was expressing such a view that forced Hedges’ mutually agreed upon divorce from the Times in 2003, only a year after sharing in a Pulitzer Prize for the paper’s coverage of global terrorism. It was that very coverage that radicalized his critique of American society and resulted in a commencement address at Rockford College in Illinois so scathing of the national ethos that he was jeered off the stage.

There are few heroes in Death of the Liberal Class, and most of them are martyrs or nearly so — uncompromising figures of the left such as the activist priest Daniel Berrigan, historian Howard Zinn, linguist Noam Chomsky, and journalist I.F. Stone.

Hedges himself belongs in this company — a purist to the point that he regards President Obama as a corporate figurehead who “lies as cravenly, if not as crudely, as George W. Bush” and who “shoved a health-care bill down our throats that will mean ever-rising co-pays, deductibles, and premiums and leave most of the seriously ill bankrupt and unable to afford medical care.”

In other words, Chris Hedges is no reformer; rather, he is a genuine revolutionary as fanatical in his own way as any Tea Partier of the right and worth reading for the uniqueness that gives him. — Jackson Baker

The Anti-American Manifesto

By Ted Rall

Seven Stories Press, 284 pp., $15.95 (paper)

With all due deference to Dorothy Parker, Ted Rall’s The Anti-American Manifesto isn’t a book to be tossed aside lightly. This seditious collection of angry ramblings by cartoonist turned columnist turned fifth columnist should be fired from a cannon on the Fourth of July in celebration of the First Amendment. The Anti-American Manifesto is a bellicose call to arms wherein Rall invites more passive lefties to join forces with armed racist skinheads and any other group, regardless of ideology, to destroy the United States government. Rall intends to be a 21st-century Thomas Paine, but The Anti-American Manifesto is common nonsense.

Revolution, real pull-out-the-guns-and-use-them-against-the-rich-first revolution, is Rall’s solution for everything, including the federal debt. “All it takes is one little Revolution to declare all those treasury bonds null and void,” he writes as if a nasty civil war would cause lender nations to suddenly forget their financial interests. Where we get the money to bury our war dead and rebuild is an issue Rall never really gets into. Neither does he mention the warlord gangsterism that might emerge in the third-world rubble of a post-revolution America. That outcome, he insists, can only happen if we sit on our fists and do nothing.

Rall, like many Americans, is troubled by the direction his country is headed. And in troubled times like these, who can blame him? When he claims that the greatest achievement of the government and its allied corporations and media shills is that it’s convinced us that there’s “nothing we can do about anything,” he is entirely on point. Then there’s this little Hitler comparison: “Perhaps we shouldn’t judge the Fuhrer too harshly, after all, he has a few things in common with Barack Obama.” The commonalities in question: They are both insulated leaders surrounded by yes men.

Though grave missteps, from manifest destiny to our great Iraqi misadventure, are a shameful matter of U.S. history, the ultimate truths of Rall’s bloody conclusion are anything but self-evident. The informed, justifiably angry, but tragically misguided author subsequently plays up the virtues of societies where government leaders live under the real threat of assassination. Quoting a bit of unattributed graffiti, he puts forward the specious notion that a single nonrevolutionary weekend is infinitely bloodier than a month of total revolution.

At every turn, Rall, now taking his place as the unhinged Glenn Beck of the left, wounds his credibility with the one conclusion that can be drawn from his many proofs: Some violence is required. He games out the various doomsday scenarios that will surely come to pass if we don’t fight, as though rebellion weren’t a doomsday scenario in and of itself. — Chris Davis

The Horror! The Horror! Comic Books the Government Didn’t Want You To Read!

Selected, edited, and with commentary by Jim Trombetta

Abrams ComicArts, 304 pp., $29.95

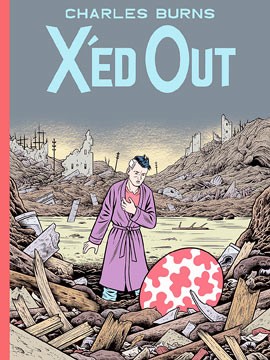

X’ED OUT

By Charles Burns

Pantheon Books, 56 pp., $19.95

“Murder, mayhem, robbery, rape, cannibalism, carnage, necrophilia, sex, sadism, masochism, and virtually every other form of crime, degeneracy, bestiality, and horror.”

It’s right there on the back cover, describing what you can find in the pages of The Horror! The Horror! But there’s an asterisk, too, indicating that the quote is from a 1955 U.S. government investigation into comic books. Thus, what we have in this impressive, well-researched book: the horror and crime comics of the 1940s and ’50s, which were so “evil” as to bring down the might of the federal government to censor them from impressionable youths of the time.

Leading the charge against comics was Dr. Fredric Wertham, whose Seduction of the Innocent made him the bogeyman of the comic-book medium. Government censorship, we know (right?), is not a good thing. But that’s what the Comics Code Authority did beginning in 1954, thus eradicating the most popular comics of the day. That’s not to say the opening quotation above isn’t accurate: You can find all manner of “murder, mayhem” etc. (and more) in the pages of those comic books, which editor Jim Trombetta has resurrected.

Hundreds of stories and covers are reproduced in The Horror!, artifacts virtually no one has seen since the mid-century. Accompanying them are essays by Trombetta. The Horror! is a must-have for comics fans and comfy-chair historians alike.

Also out is Charles Burns’ X’ed Out, touted as “the first volume of an epic masterpiece of graphic fiction in brilliant color.” I can’t say what the rest of the series will hold, but X’ed Out is indeed an auspicious start. Burns (Black Hole) is a master at “staging” a page — some of them here have solid color panels with considerable aesthetic appeal and increased emotional resonance.

Something bad has happened to the main character, Doug, in X’ed Out — some juju that’s left him bedridden and psychologically injured. Much of the story is spent in Doug’s dreams, where Burns introduces elements that begin to get explained by the end of the volume (and, one presumes, with a bigger payoff to come in future installments). The middle section is a flashback to a time when Doug was whole, performing at an underground art party. That’s where he meets the photographer Sarah, and what happens next is anyone’s guess. Can’t wait to find out.

— Greg Akers

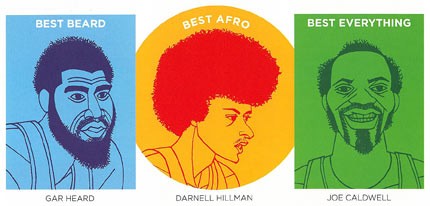

FreeDarko Presents: The Undisputed Guide to Pro Basketball History

By Bethlehem Shoals et al.

Bloomsbury USA, 213 pp., $25

FreeDarko is a small collective of intellectual, subcultural pro-hoops enthusiasts under the lead of the self-named Bethlehem Shoals. Initially web-based, the FreeDarko crew’s cult following swelled when they made their book debut with 2008’s Macrophenomenal Pro Basketball Almanac, which was a novel, witty, and provocative examination of the contemporary tenor and talent in the National Basketball Association.

This follow-up — which adds a handful of new writers to the FreeDarko core — backtracks to the origin of the sport and investigates the game’s growth from inventor James Naismith (“The Peach Basket Patriarch”) to the legacies of Allen Iverson and Shaquille O’Neal.

Like The Macrophenomenal Pro Basketball Almanac, The Undisputed Guide to Pro Basketball History has the size, shape, and design of an elegant textbook, with colorful and striking illustrations, charts, and graphs. The result amounts to a prettier, brainier alternative — or perhaps supplement — to Bill Simmons’ straighter, more culturally clueless but still essential Book of Basketball.

As you might expect in a book about the history of the league, the Memphis Grizzlies aren’t much of a factor here. There is a quick reference to Jerry West’s tenure with the team in a chapter on West, Elgin Baylor, and Oscar Robertson and to Marc Iavaroni’s “dismal Memphis tenure” in a sidebar on other teams’ attempts to replicate the style of the Phoenix Suns. But the only place where the Grizzlies figure prominently is in a chapter on “court cases, contracts, and caps,” where the team’s 2008 trade of Pau Gasol to the Los Angeles Lakers is the lead item in a summary that darts back to the 1970s to document the evolution of the league’s complex financial system and its relationship to the on-court product. The conclusion: “The Pau Gasol deal may not have been an equitable basketball trade, but it was an equitable NBA trade.”

— Chris Herrington

BADASS:A HARD-EARNED GUIDE To living life with style and (the right) attitude

By Shannen Doherty

Clarkson Potter, 254 pp., $25.99

Shannen Doherty (Memphis-born) has made the transformation from bad girl to badass — or that’s what she wants you to think. Now that she’s worked through her own issues, she wants to help you become a badass too.

Doherty’s new book, Badass, is intended as a self-help guide to move women away from negative relationship patterns, insecurities, and the like. She uses stories from her “Brenda Walsh” days, when the 90210 actress was known for her bitchy behavior, to show women that if she can change, anyone can.

Unfortunately, most of the book comes across as juvenile and contrived. For example, after about 100 pages extolling Doherty’s virtues of badass-ness (integrity, class, compassion, sensitivity), the book turns into a shallow guide to living the badass life, which includes making sure “that we have great shoes, purses, hairstyles, and nails.” Doherty even includes a list of badass lipstick shades. (FYI: Russian Red by MAC tops the list.) The former Charmed star goes a little Martha Stewart by the end of the book with tips on decorating your patio and using vintage fabric. She even includes a recipe for her dad’s Chilean sea bass.

I’m all for cutesy all-purpose guides to modern-day domesticity, but these helpful tips hardly make up for lines like, “Men, like dogs, respond well to praise. Give your man lots of it.”

The book does contain some common-sense advice, though. Doherty writes of her experience trying to control past boyfriends and fix their negative behavior, a pattern many of us fall into. She advises women to view relationship-controlling behavior as a sign that it’s time to “use my confidence and my courage to move on.” That’s good advice.

Doherty’s tables and charts, like the Badass Growth Chart or the list of bitchy traits vs. badass traits, however, overshadow any tips that may actually help people move into a healthier sense of self.

Diehard Shannen Doherty: Badass might be a fun gift, but don’t expect it to help you make real changes.

— Bianca Phillips