For the best reviews of the new cyborg flick Ex Machina, go read the comments on the movie’s YouTube trailer. There, you will find a variety of good observations, such as, “Why is the A.I. almost always female?”; “Maybe if people would stop treating their A.I.’s like shit then they wouldn’t go nuts and want to kill everyone”; and “I think this movie is made for the blow up doll fanciers. What Sick Bastards, that makes us humanize toaster ovens.”

I will confirm Ex Machina is a movie about “humanize[d] toaster ovens” that are created by a sick bastard. The film follows Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson), a young programmer who has won a vaguely defined online contest. His prize is a week with Nathan (Oscar Isaac), a genius billionaire who lives alone on a Norwegian estate that looks like a cross between Camp David and Rivendell.

Ex Machina

Nathan is a supposedly chill dude (spoiler alert: he’s not really chill) who also happens to be developing cutting-edge robots. He needs Caleb, a freshman with a big heart, to interact with a robot named Ava in order to determine whether or not she has achieved sentience. Caleb is in over his head and knows it, but he is too curious to back out of the increasingly weird circumstances. Nathan, meanwhile, is revealed as an unstable alcoholic who abuses his sole employee, a beautiful, silent servant named Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno).

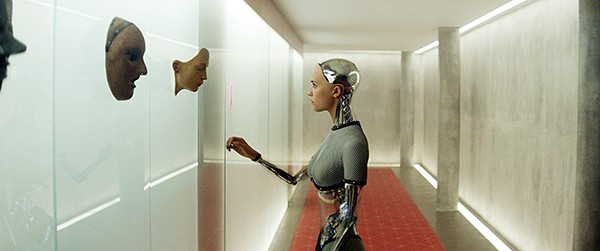

We first meet the robot Ava (Alicia Vikander plus a team of motion-graphics artists) from Caleb’s perspective: She is silhouetted against a window in her locked chambers. She has a shy, sad-eyed, Natalie Portman vibe. Her artificial face is prosthetically masked with human features, but her body looks like a shapely version of the see-through computer my nerdy high school boyfriend once built. When Caleb is allowed to speak to her through a glass, Ava points out that she understands his “microexpressions.” She can tell he likes her, maybe too much. From there, Ex Machina is standard fare, as conjectural parallel realities go: Boy meets Robot. Boy loves Robot. But Robot is a robot. What will become of Boy?

Alicia Vikander as Ava

The script, while competent, is laden with grating cultural reference. Nathan and Caleb cite Prometheus while they drink wine and eat sushi. In one scene, Nathan explains his life philosophy through the extended metaphor of a Jackson Pollock painting. Caleb, for his part, regularly says things like “If you’ve created a conscious machine, it’s not the history of man. That’s the history of gods!”

For a movie about the stunning reach of tech, the tech in Ex Machina is weirdly campy. In order to gain entrance to the most preciously guarded scientific research facility in the world, all Caleb has to do is pickpocket a key card, the kind you get at Days Inn. The sci-fi logic of the film, which could make it worthwhile, also falls flat. When Nathan gives Caleb a tour of the A.I. batcave, a room scattered with detached prosthetics and eerie light tables, he holds up a brain-shaped piece of glowy glass and tells Caleb it is the A.I.’s mind. Thought sequences, he explains, are downloaded in real time from billions of searches. Imagine what it would actually be like to talk to something that formed its reality based on web searches. I just typed “What is…” into Google and the second and third suggested searches — based on some seriously high-level algorithmic intelligence — were “What is Coachella?” and “What is a thot?” There may be some epistemological problems with crowd-sourcing.

A version of Ex Machina told from Ava’s perspective would have been infinitely more interesting. Near the end of the movie, Ava tries to make herself look human by donning a wig and applying layer after layer of prosthetic skin to her robot body. She stares in the mirror, investigating her weird, new self. Save yourself the trouble of seeing this movie and instead go read Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, where she describes cyborgs as “the final appropriation of women’s bodies in a masculinist orgy of war.” It’s a start.