Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

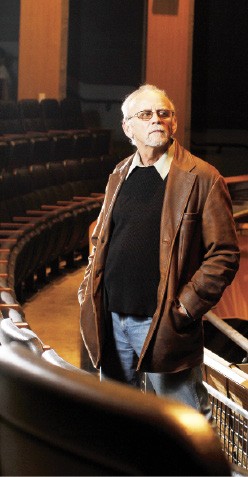

Jackie Nichols

Call it a #Metoo moment. Call it the “Weinstein effect,” a recently coined term inspired by Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein’s lurid story and used to describe the watershed moment when women collectively stood up to sexual predators in positions of power and said, “no more.” Call it whatever you want. Now that Playhouse on the Square has completed its independent investigation into allegations of sexual misconduct at Playhouse on the Square — and possible abusive behavior by the theater’s founder Jackie Nichols in particular – women who’ve contributed to that investigation want their stories told. And want them to matter.

On Dec. 1, 2017, Angela Russell posted an explosive allegation on her Facebook page against Nichols. She accused him of sexually abusing her in the 1970s, while he was married to her mother, Diana, his first wife. The abuse allegedly happened over a three-year period starting when she was only 6 years old. In a statement published by The Commercial Appeal, Nichols flatly denied Russell’s allegations.

Russell, now 49, is the owner of Underground Art, a 25-year-old tattoo studio in Cooper-Young. She says she’s been trying for decades to get Nichols to take accountability for what he allegedly did. Her claim is backed by a high school classmate who remembers hearing the story from Russell in the 1980s, and by other friends who say Russell told them about it in the 1990s.

A month after that post appeared on Facebook, a group of 20 Playhouse on the Square employees, spearheaded by two company members who are no longer with the organization, interrupted a board meeting to make a statement and present a list of demands.

“Playhouse stands on a national stage,” the statement read. “Our actions will be an example to other artists and organizations in Memphis and around the country. We want to send a strong message: ‘Not here. Not ever.’ The people in this room today have a responsibility to make that principle a reality.”

Demands included the “immediate suspension of Jackie Nichols pending a full investigation,” and for the board to “additionally look for other individuals or incidents that may not already have been brought to light.”

On January 5th, Nichols took a voluntary leave of absence. A week later, Jennifer S. Hagerman of the Burch Porter & Johnson law firm was named to investigate complaints against Nichols and unknown others, per the employee statement. A separate review of policies and procedures was also announced.

A little more than two months later, on March 13th, Nichols resigned his position as executive producer. A statement from the Playhouse board made no mention of the investigation and praised the outgoing leader’s unparalleled service to Memphis theater.

Playhouse’s refusal to release the Burch Porter & Johnson report has not been well received by some of the women who met with Hagerman. In addition to Russell, the Flyer has interviewed four other women who spoke to the investigators and alleged sexual harassment by Nichols: Louisa Koeppel, Alice Raver, and two women who asked to have their identity protected for personal and professional reasons. Here are their stories.

[pullquote-1] When Louisa Koeppel read Angela Russell’s Facebook post last fall, it brought back a memory of being driven home one night in the 1980s by Nichols after she’d been baby-sitting at his house.

“Jackie had been drinking,” Koeppel recalls. She says she remembers feeling her weight pressing against the passenger door while he said things such as, “Too bad you’re the babysitter,” and “You’re starting to look like a woman.” She says she was scared enough to consider opening the car door and rolling out of the slow-moving vehicle.

Koeppel, now 45, is a dancer with Project: Motion and member of Hutchison’s fine arts faculty. She didn’t want to share her story on social media as Russell had, but she felt compelled to speak to the investigator. Her father, Fredric Koeppel, formerly The Commercial Appeal’s food and culture writer, also remembers the night in question.

“One night Louisa came into the house very upset,” he wrote in a statement supporting his daughter’s story. Louisa told her father that Jackie had “hit on her” in the car. “He put his arm around her and tried to kiss her,” Koeppel’s statement continues. “Jackie is a longtime acquaintance of mine, whom I see out and about occasionally. I never brought up the issue of his misconduct with my 13- or 14-year-old daughter, but every time I saw him, I thought about what he had done.”

Alice Raver says she thought of Playhouse on the Square as her “safe space” when she was a teenager. The West Memphis native, now working as an actor in Nashville, says she still remembers it that way. Her parents argued at home, she says, and the theater was where she went to get away from it.

“It was glorious being part of Playhouse on the Square, in spite of what Jackie did,” she says.

As a teenager in the 1970s, Raver began doing youth theater at Circuit Playhouse. Raver says she was impressed by Nichols’ theater operation because his company was producing edgy plays like When You Comin’ Back Red Ryder while other theaters around town were mounting musical confections like Brigadoon. Raver was eager to do more around the theater, and when opportunities to help out with lighting, set construction, and box office work presented themselves, the 15-year-old jumped at the chance.

“I had keys,” she says. “I felt so privileged to have that responsibility.”

Raver says she can’t remember the first time Nichols was inappropriate. She says there were stolen kisses and comments about her body that happened when they were alone together, and that they could be usually be diverted with mild resistance. Like the keys she carried, and the responsibilities that went along with them, she says the attention felt like validation, bolstering the esteem of an awkward teenager with acne and braces. “I was flattered that he showed an interest,” she says. “Maybe he thought I was cute.”

Raver says the kisses and comments eventually became less frequent and stopped when she took a break from the theater to attend college.

Two other women who spoke to the investigator also shared their stories with the Flyer but asked that their names be withheld for personal and professional reasons. The first was 14 and doing youth theater with Circuit Playhouse when, according to her account, Nichols asked for help taking costumes to the costume shop.

“I was gathering costumes when he came up to me and started kissing me on the mouth,” she says. Having very little experience kissing at that point in her life she initially responded by kissing back. A moment later she pushed him away asking, “Do you have any idea how old I am?” When she told Nichols, he allegedly responded saying, “You don’t have to mention this to your mother. “

The last person to speak to the Flyer before publication tells a story much like all the rest. She says the groping began at 15. Sex was allegedly solicited when she was 17.

[pdf-2] Jackie Nichols’ contributions to the performing arts and culture in Memphis are difficult to overstate. Loeb Properties may have brought Overton Square back from the brink of demolition, but Nichols and Circuit Playhouse Inc. (CPI) literally set the stage for the now-thriving entertainment district’s resurrection and revitalization.

Nichols launched his company in 1969. In 1975, he created a new flagship theater, opening Playhouse on the Square on Madison Avenue. In 2010 he moved Playhouse out of its second home in the old Memphian Theatre just off the northwest corner of Cooper and Union and into a custom-built, $12.5 million, performing arts facility across the street.

Nichols was also instrumental founding TheatreWorks and The Evergreen Theatre, a pair of performance spaces made available for smaller companies to co-occupy. These venues have enabled the growth of independent theater, comedy, and variety arts scenes, enjoyed by thousands of Memphians today.

Playhouse’s theater education program is a powerhouse, reaching 30,000 children annually. Its leaders have a strong history of child advocacy and responsible training.

For these reasons and others, many people — especially theater people — are grateful for everything Nichols has accomplished in Memphis. Playhouse on the Square has grown from a tiny regional theater into a professional company with enviable physical resources. It’s the kind of resounding success that’s hard to argue with — the kind of success that sometimes makes dissenting voices hard to hear.

“I am proud of what we have built together,” Nichols wrote in his March 13th letter announcing his resignation, citing his theater’s $3 million annual revenue and its 40,000 yearly attendance. “I have reached the point in my life where it is important to me to share the insights I’ve gained and lessons I’ve learned with my colleagues and peers so that I may contribute to the professions that have given me so much happiness and fulfillment.”

In a separate media release also dated March 13th, Playhouse on the Square announced that interim executive producer Michael Detroit would officially assume Nichols old job full time. In a statement to the Commercial Appeal Nichols said not conducting an investigation into his conduct would be “irresponsible,” but his March 13th resignation/retirement announcement did not mention the investigation or its findings.

The women who spoke to the Flyer said their interactions with the investigator were professional and thorough, but Russell questions why the results of the investigation have not been made public.

“This absolutely lacks accountability, culpability and transparency,” Russell wrote in response to Tuesday’s announcements. “There is no mention that the other women who’ve come forward were also underage when they were abused. There is no mention of any allegations against other members of the organization. There is no mention of complicity by other members of the organization.

“We will continue to pressure Playhouse to release that report, to take accountability,” she concluded.

Russell’s announcement apparently runs counter to attitudes at Playhouse on the Square. When asked about the silence in regard to Hagerman ’s investigation, Playhouse board member and media consultant David Brown said there will be no summary report forthcoming.

“There will be no release of findings,” Brown wrote, responding to an email from the Flyer. “Playhouse never said it would publicly release a report.

“I can tell you that the last alleged event was from the 1980s, nothing in the past 34 years,” he continued. “[Nichols] denies all of the allegations that came up during the investigation.”

The #eyesonplayhouse hashtag Russell uses hasn’t exactly caught fire, but it only takes a little social media searching to locate negative threads about POTS on the internet. The commenters’ concerns revolve around a lack of transparency and an inability to determine what problems, if any, may have been identified by the investigation, and whether or not Nichols’ decision to leave the organization — a decision that hasn’t been officially acknowledged as being connected to the investigation — is part of a meaningful solution. The fact that POTS did not acknowledge its investigation in media releases regarding the 49-year-old institution’s historic change of leadership does nothing to allay concerns that problems, if they exist, may be related to a culture inured to those types of actions, rather than to a specific individual.

Maybe all this is simply the Weinstein effect. Maybe it’s social media’s ability to keep unpopular ideas moving around the internet when legacy media isn’t paying attention. However we choose to label this particular cultural moment, one thing is certain: These are no longer the kinds of concerns that go gently into the night when prominent men retire.