JB

JB

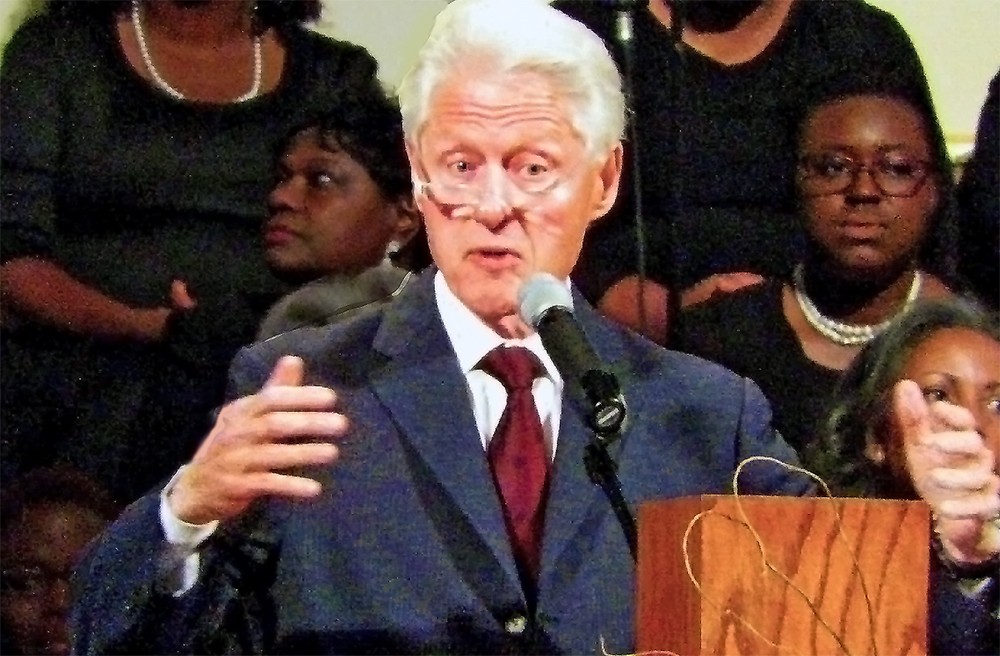

President Clinton delivering eulogy on Saturday

Saturday’s funeral service for Judge D’Army Bailey at Mississippi Boulevard Baptist Church brought out the multitudes, crossing barriers of age and race and class, just as his chief creation does, over and over — the National Civil Rights Museum, where the civil rights pioneer/author/actor/judge lay in state on Friday.

Bailey was remembered Saturday through testimonies of those who knew him well, who had worked with him, who had loved him, and who had benefited from his presence in the world, which had ended last Sunday when the renaissance man — who, as his brother Walter, a longtime Shelby County Commissioner and an eminence himself, said on Saturday, had almost seemed immortal — died from the effects of cancer.

Besides his brother, those who offered reminiscences about D’Army Bailey included the church pastors, David Anderson and Lynn B. Sandridge, Bailey’s Circuit Court colleague Jerry Stokes, Judge Bernice B. Donald of the 6th circuit court of appeals, friends Aubrey Howard and Richard Glassman, Mayor A C Wharton, and the Revs. James LaVirt Netters and J. Lawrence Turner.

Superb music interludes were offered by the Mississippi Boulevard Christian Church choir, by singer Chequita Monique, and by pianist Christopher Ward.

And, as befitting D’Army Bailey’s eminence in the world and the significance to that world of Bailey’s gift to it, the National Civil rights Museum, he was eulogized by a former president of the United States, Bill Clinton.

The former president paid tribute to numerous qualities of Bailey, his intelligence, his imagination, and his political sense, “but the thing that made him special to me…was that he was comfortable with all kinds of people, but he lived and died a movement politician “

Having established the basic trope of “movement,” Clinton used it in different ways to describe Bailey:

• as a young man in a hurry, moving so fast that in Berkeley, California, in the ‘70s, after law school, “he gets himself elected” an alderman, “then gets himself unelected” — this being a reference to a recall election that befell activist Bailey in that hotbed of controversy in that volatile tim.’

• as a man who, at all times at all his ages, knew how to move other people to a goal. {In an aside, Clinton said, apropos young people, “you need to be moved.”)

• as an exception to the rule that so many movement types “care about people in general, but they’re not so keen in particular.” Said Clinton: “D’Army Bailey cared about people, he was keen about people in particular,” and he knew how people, “all kinds of people,” felt when they were asked to move.

• as a man who, once having established a goal, knew how to move toward that goal and had the discipline to keep momentum toward that goal from flagging —a case in point being the hard bargaining that it took to acquire and pay the mortgage on the then bankrupt Lorraine Hotel, the site of Dr. Martin Luther King’s death and of the future National Civil Rights Museum. Just think, Clinton reminded his rapt audience, “it could have been a parking lot by now.”

“For people of a certain age, the power of this Museum will never die,” said the former president, who was on hand for its unveiling in 1991 and at important intervals since.. And for those of a younger age, it would serve as a way to “re-invent” the struggles of the past and to interpret those of the present. D’Army Bailey had “left the youth of America a national treasure.”

D’Army Bailey, said Clinton, knew that” institutions ae only useful to the extent that you can use them to make change.” And he knew that “to extend civil rights under the law we have to keep moving….This man was moving all his life….. He moved. To the very end he moved. And God rest his soul.”