“I was more interested in writing long magazine feature pieces than I was in breaking hard news. Let radio and TV have the games. The culture of sport interested me more.” — Frank Deford

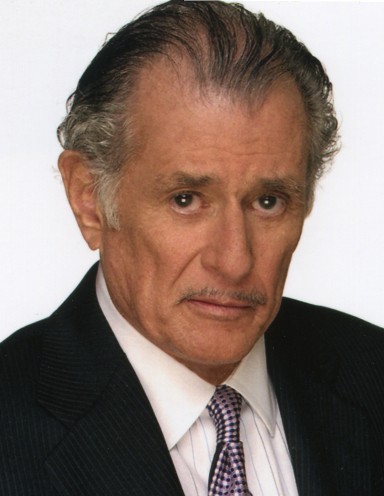

We lost a great one Sunday with the passing of Frank Deford. A kind, eloquent, honorable man with a sharp-as-a-scalpel wit, Deford just happened to make his living as a sports journalist. If you didn’t read his work in the pages of Sports Illustrated (to use a verb Deford would have rejected himself, he dominated the craft for much of the Sixties and Seventies, and well into the Eighties), you surely caught a few of Deford’s weekly commentaries on NPR’s Morning Edition. Whether his subject was international soccer (confounding), Bill Russell (greatest team-sport athlete of the 20th century), or Johnny Unitas (a personal hero from his youth in Baltimore), Deford made the games and performers we cheer somehow larger than scores, championships, or records broken. As treated by Frank Deford, sports helped expose humanity and reveal beauty, and under a spotlight not found in many other endeavors.

I reached out to Mr. Deford at two distinct stages of my life. Living in Boston as a college senior in 1991, I wrote him to ask about possibilities at The National. Deford was the founding editor of the daily sports newspaper destined to fold a few short months later. He wrote me back as though a 22-year-old college kid was a priority while he fought to keep a much larger ship afloat. His wisdom: Find a region you like and report there before considering the national stage. His was a kind way of telling me to walk before I run as a writer. I chose to report from and about Memphis, Tennessee.

Eleven years later, established as a (still-young) journalist in the Bluff City, I wrote Mr. Deford again, this time asking about my next career stage, if I needed to return to the northeast, to seek a larger market and/or a national byline. He put me in touch with an editor at a national magazine, and noted how he took a liking to a subject of mine — Stubby Clapp — during a visit to Salt Lake City when the Memphis Redbirds were in town. There was irony in that exchange: “Regional” journalism could stretch geographic boundaries. Good writing didn’t require a national readership. It required an individual’s care for the craft, and a certain delicate touch with one’s subject. Deford personified that touch for me, and I chose to remain in Memphis.

Deford and I happened to share a few coincidental commonalities. Neither of us played golf. (“The better question . . . is whether I have taken good enough advantage of the hours I have had in my life not playing golf.”) We both defined Boston sports fans well beyond Fenway Park. (“I laugh now, too, at all the Red Sox Nation crap, the myth that all New England has always worshipped the Sawx through thick and thin.”) And we both bristled at athletes or coaches who sold themselves above the team, or modern journalists who consider themselves above their subject matter. (“I was raised — infused — with a distaste for the smug and high-hat. Indeed, the worst label that a Baltimorean could give you was common.”)

Deford and I both married well, and we were both blessed with daughters. When his beloved Alex died at age 8 from cystic fibrosis, Deford turned to writing. Alex: The Life of a Child is one of 18 books Deford wrote, ten of them fiction. (I had hoped to send him a copy of my first novel, to be released in mid-June.) Perhaps the best coincidence of all, Mr. Deford and I are both Frank III.

Deford considered Jackie Robinson and Billie Jean King the most significant athletes of his lifetime, and this is perfectly Frank Deford. For Robinson and King changed the way we live, not just the sports they happened to play. And perhaps that’s the best way to remember this great American sportswriter, as a man who chronicled man’s continuing evolution, only through the lens of ball games, tennis matches, and prize fights. The final words of this column belong, as they should, to Frank Deford:

“Times change only because we who inhabit them do the changing first.”