Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera are so well-known in postcards and posters that it’s difficult to understand their work in its own right. As Walter Benjamin wrote in 1935, “What withers in the age of the technological reproducibility of the work of art is the latter’s aura … By replicating the work many times over, it substitutes a mass existence for a unique existence.”

Because of Kahlo and Rivera’s pop culture status, the quote is especially relevant to the exhibit currently at Nashville’s Frist Art Museum until September 2nd, “Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection.” Not only have we seen many of the works countless times, the exhibit’s focus on the artists as a couple threatens to overwhelm the art itself with their very celebrity.

And yet, because much of Kahlo’s work reflects her life’s traumas, such as her chronic ill health after a bus accident at age 18, her art can transcend mere celebrity if only we delve more deeply into the details. And that’s precisely what this intensely biographical exhibit does so well.

The aura of each work lives in details, too, and that’s the first revelation. Overfamiliar paintings take on a new life when one can savor each brush stroke, each nuance of shading that makes the artwork spring to life again. Beyond such epiphanies, the sheer volume of biographical detail forces us to see beyond the storybook tale of the artists’ lives.

The Gelman collection also includes other leading artists of the time, such as Guatemalan Carlos Mérida, whose Festival of the Birds fuses geometric abstraction with the then-widespread fascination with Mexicanidad folk identity. This interplay is also apparent when comparing Rivera’s most widely known Mexicanidad work, such as Call Lilly Vendor, with his forays into Cubism when living in Paris from 1907 to 1920. Seeing the intriguing geometry of his The Last Hour (1915) elucidates the abstracted graphic elements of his later, more famous nativist works.

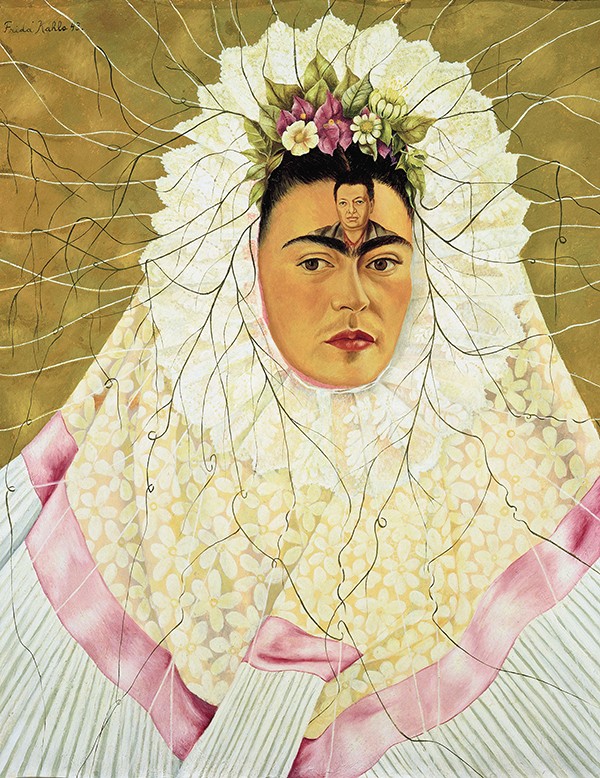

Diego on My Mind (Self-Portrait as Tehuana), 1943.

It also sets the context for the celebrity Rivera enjoyed by the time he met Kahlo, 20 years his junior. That celebrity, and his financial security, convinced her parents to give the union their blessing. (Examples of Kahlo’s German father’s stark architectural photography offer a clue to his sympathy for her artistic aspirations). Eventually, many infidelities colored their entire marriage, though after renewing their vows in 1940, their relationship settled into a state of mutual non-monogamy.

This turbulent romance is expressed in many of Kahlo’s most revered works, such as Diego on My Mind. But an even clearer window into their relationship is the home movie footage perpetually looping on a large screen. In it, as the pair makes a good show of being happy spouses, the tense body language between them is palpable.

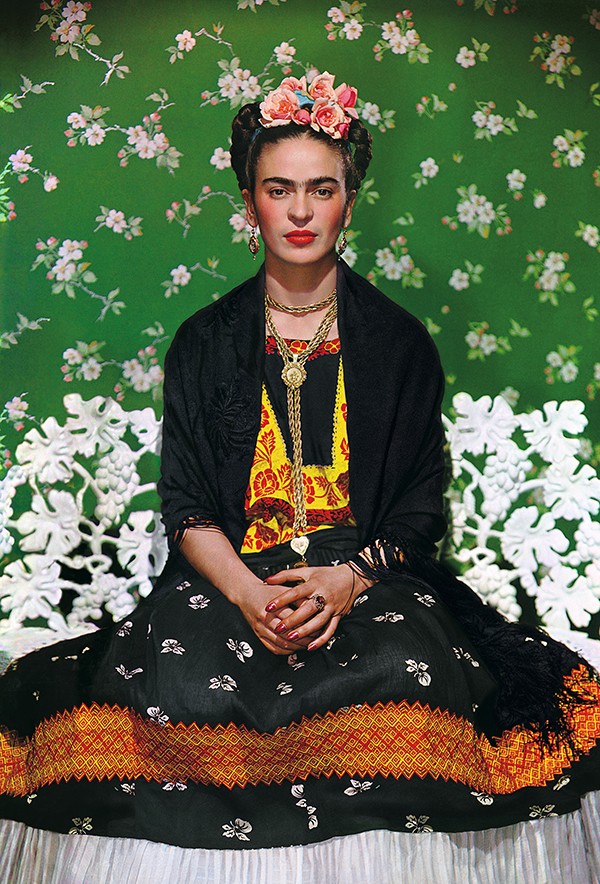

Seeing the two strolling through the courtyard has an aura all it’s own, and that’s true of other exhibit highlights that were not created by either artist in the strict sense. Several of Kahlo’s distinctive dresses, so emblematic of her love of Mexican folk culture, are showcased. And there are portraits of both Rivera and Kahlo by others. The photographs of Kahlo by her erstwhile lover, Nickolas Muray, are groundbreaking not only for their use of color in 1939, but for their stylized portraiture. And images like songwriter Patti Smith’s 2012 photographs of the painter’s crutches and corset reflect Kahlo’s ongoing cultural relevance.

Though there are many insights into Rivera’s work as well, this is a show dominated by Kahlo’s artistic trajectory. And, from her rare lithographs depicting her miscarriage, infused with her fascination with medical illustrations, to her politicized charcoal sketch of the Statue of Liberty, there are many surprises that add the shock of the undiscovered to our knowledge of Kahlo and offer fresh perspectives on the troubled relationship that framed her life.

“Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism” is on view at Nashville’s Frist Art Museum through September 2nd.