New residential developments sparkle on both sides of Danny Thomas Boulevard north of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Optimistic names like Metropolitan Apartments and Uptown Homes seem to promise a brighter future to these once-blighted streets.

Just north of Uptown, past Chelsea Avenue, after Danny Thomas becomes Thomas Street, the strip of black-owned and black-run barbershops, hot-wings stands, juke joints, and nightclubs looks like something out of this city’s celebrated past. It’s the kind of soulful authenticity that distinguishes Memphis from other places. In fact, some locals describe Thomas as the real Beale Street.

As gentrification approaches from the south, one wonders if Thomas Street — the jugular of black commerce in North Memphis — will eventually meet a fate similar to Beale Street’s. Beale Street — now tourist-driven, with its neon signs, cover bands, and thriving crowds — once pulsed with almost exclusively black commerce and culture until the city’s “urban renewal” plan indiscriminately leveled many black businesses in the 1960s.

Thomas Street straddles a line between much-needed civic improvement and careful preservation.

While it’s easy to feel nostalgic about the city’s past and to simply equate Thomas and Beale and independent black culture as an endangered species in Memphis, one iconic Thomas Street figure wishes other people could “see through my eyes.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

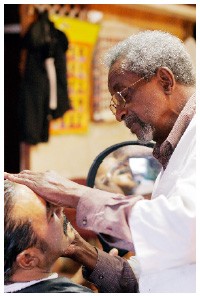

Warren Lewis has witnessed many changes on Thomas Street and instigated a few of the better ones himself. In 2004, the city renamed a block of Thomas between Chelsea and Guthrie avenues “Warren Lewis Street,” to honor the barber and community activist.

“I’ve been here 55 years, so I’ve seen a lot of things happen,” Lewis says. “I came to Memphis December 3, 1951. North Memphis was blooming,” he continues. “We had the Savoy Theatre at Firestone and Thomas, the Harlem House [restaurant]. Johnnie Currie’s place [Club Tropicana] was down there at 1331 Thomas. Little Richard, Fats Domino, all of them played there. Used to be a racetrack and a few big plants. Furniture stores, grocery stores, shoe shops, Jew Thomas’ big clothing shop, and little juke joints all around. I opened up my first shop at 612 Life Street, right off Thomas Street.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Barber and community activist Warren Lewis has been on North Thomas for 55 years. His patented hair-styling technique involves burning hair with a candle and has been featured on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.

Lewis bought his current shop at 887 Thomas in 1965. He gradually augmented that structure with materials salvaged from other properties he owns.

“I paid for it as I went,” he says.

The expanded complex includes two rooms of barber chairs, numbering about a dozen, three video-poker machines, and a deli. A TV perched at the end of one row of barber chairs broadcasts Lewis’ highlight reel of news, late-night talk-show appearances, and an artsy documentary, Who is Warren Lewis?, made in 1990.

On the screen, Lewis practices his patented hair-shortening technique. He uses cathedral candles, or tapers, to singe away the hair. In one segment, Lewis works on Jay Leno’s drummer, whose eyes pop and roll like the Little Rascals’ Buckwheat as the smoke rises from his head. Leno howls as Lewis describes a “small accident” he once had styling hair this way.

“The scent goes up, and the ash falls down,” Lewis explains.

He adapted the technique from something he learned growing up in the country. When his family killed a chicken for supper, Lewis plucked the feathers and burned off the fine fuzz left over before cooking the bird.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Back in real life, Lewis’ place fits the image of the classic black barbershop. Neighborhood folk come and go, whether they’re in for a cut or not. Often the number of full seats in the waiting area outnumbers the full barber chairs. People chatter about neighborhood news. Old men tell lies, guffaw, and slap knees. Politicians stump at Lewis’. As the proprietor has developed his charitable reputation, people in need stop in and ask “Who is Warren Lewis?” so much he had the slogan printed on bumper stickers and distributed throughout the section of North Memphis that’s come to bear his name: Warrentown.

Lewis worked in the Juvenile Court system between 1965 and 1968. “I knew all the kids around here in New Chicago,” he says. “I asked them, ‘Why are you here in Juvenile Court?’ ‘What’s the problem?'”

He discovered that most were petty thieves, and he founded an organization to find work for youths, who today would be called “at risk.”

“I came back to the community and organized the Black Knights,” Lewis says. “Me and Isaac Hayes both almost starved to death when we were little boys. We organized the Black Knights, and Isaac Hayes was vice president. All the guys at Stax, they would give us money to operate.

“We came up with a food program called the Emergency Assistance Bank. We had truckloads of food coming in every day. People depended on me. A.C. [“Moohah”] Williams [of WDIA] brought all these brooms and rakes. I used to have two buses to carry kids from neighborhood to neighborhood every morning. We called it the ‘broom brigade.’ We split the money we made between all the kids.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“Our goal was to try to help some of these young people. We couldn’t help them all,” he says.

The Black Knights dissolved as Stax Records sank in the mid-’70s.

Lewis once dreamt of building a Warrentown strip mall to stimulate the local economy. He now believes that some destruction must precede progress on Thomas.

“Houses haven’t been painted in 35, 40 years. They need to be,” he says, his voice softening as if reading aloud to a child at bedtime. “Demolished,” he says. “Anytime you clean something, you won’t have as many flies and roaches. If you clean up a neighborhood, you won’t have as much crime.”

Lewis hopes that the Uptown development continues its way up Thomas Street.

“Ain’t no ifs, ands, or buts about it. We need it to clean up the neighborhood,” he says. “After Firestone, International Harvester, and American Bridge started closing down, everybody in North Memphis run off and left me here. I’ve been here and fought to get things done. I have had hope that things would be better. I’ve never had any real money, but what I’ve had, I put it back into the community.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Demolition reduced one of Thomas Street’s landmarks to a vacant lot. American Recording Studio, where Elvis Presley recorded “In the Ghetto,” literally in the ghetto, was torn down in 1989.

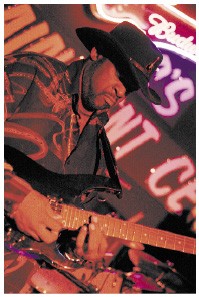

Though Thomas Street no longer churns out the hits, music still thrives on the strip. As the czar of Thomas Street nightlife, L.D. Conley, puts it, “Seems like live music is the thing everybody wants to get off into now.”

Venues of all colors and sizes dot Thomas and its cross streets. Jessie Hurd has run One Block North, just off Thomas at 645 Marble Avenue, for a dozen years. The Memphis Connection band plays the little joint on Friday nights.

Another local, “MC Jammer,” is re-opening the beautifully painted J&J Bar and Grill at 1065 Thomas. He wants to give blues musicians a venue off Beale to play live seven nights a week.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Much of the music is ‘old school’ rhythm and blues on North Thomas.

The thick competition between Thomas clubs isn’t the only challenge facing impresarios of the night. In late October, the Memphis Police Department boarded up one of the Thomas strip’s most popular clubs for reasons that made old Beale colorful: shooting, cutting, scrapping, drugging, and prostituting. Allegedly.

Roy Hughes is a flashy man, even by nightclub-owner standards. He disputes the litany of charges levied against his place at 1217 Thomas — humbly named Club Hughes and decorated with a giant illustration of a Manhattan. He says his story is that of a small businessman victimized by unjust and overzealous local law enforcement officers.

“I’ve been in business here around four years,” Hughes says. “I was a contractor with Memphis Housing Authority. I bought [the building] as a shop for my business. I changed it to a restaurant because it had been a grocery store before, and people would come in looking for plates, so the business was already there.”

The difficulty of being in two places at once forced Hughes to make another change.

“I turned it into a club because when it was a restaurant, food and money was going out the door,” he explains. “I’d be out working on houses and I wasn’t here to babysit my business, and it went down. A nightclub was more convenient for me to keep up with my proceeds,” Hughes says.

The club expanded to both sides of the building, and Hughes’ clientele grew with it.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“The more my clientele grew,” he says, “the more my problems grew, and the more I became a target. I became a main point of focus, despite there being other clubs around here that do the same amount of business and more.”

If Hughes is a target, police hit the bull’s-eye on Christmas night 2005.

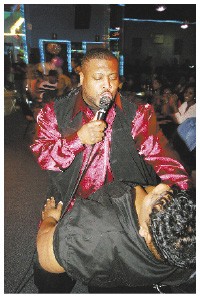

The standard Club Hughes crowd — large and overflowing — came to celebrate that night. Another typical Club Hughes event — a visit from the fire marshal — soon followed.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“The fire marshal told me, ‘Hughes, I’m not the kind of guy to fuck up your livelihood, but you’ve got some people hatin’ on you,'” Hughes says. “He came back to count the crowd on Christmas and said to let everyone out one by one. He said, ‘When I get through counting ’em, you can let them back in to your capacity.’ But when they were coming out, the [police] officers [gathered outside the club] said, ‘Go on home; he’s closed.’ They were out here blocking people in, towing cars. They did us like a dog that night.

“I have a crowd of [age] 18 on up. The police led everybody out into the streets. The fire marshal counted 400, but when the news came out that following Monday, it said 530. After the club was empty they started harassing everybody. Some of the youngsters decided to party out in the street and started singing my anthem: ‘We at Hughes, we at Hughes,'” says Hughes.

He alleges that the police pulled some of his ejected patrons over as they drove away from the club and found a firearm in a vehicle.

“That’s where their ‘gunman’ came from,” Hughes says. “It was some young dude who said something. The police grabbed him and he broke and ran. They didn’t catch him, and he ended up back in the crowd laughing at them. When it came on the news, it said a gunman chased the police.

They said I incited the riot by grabbing the microphone [during the evacuation] and telling everybody, ‘Don’t let them fuck with y’all.’ I told them to wish the officers and the fire marshal a Merry Christmas on the way out.

The police issued a press release that classified the event a “riot” and the story took.

Hughes has found other amusing inconsistencies between what the police say and do about his club.

The petition to close his club includes, among many other things, a description of an incident earlier this year in which MPD sent minors undercover into the club to — successfully, it turned out — purchase alcohol. To which Hughes cracks, “When they raided, they said it was too dangerous for the police to come in here. But they sent minors in here to get beer. If it’s too dangerous for the police, how in the hell can they send minors in here?”

In addition to serving minors, the police investigation turned up incidents of drug sales and open use of marijuana in Club Hughes. According to the report, the atmosphere was “tolerated and facilitated by the owner, management, and employees. As such, the investigation witnesses, the atmosphere at Club Hughes is one of relative lawlessness in which illicit drugs are openly used, fighting and drunkenness are rampant, and authority, including police authority, is disobeyed.”

“In a club it ain’t hard to find someone doing something wrong,” Hughes counters. “A nightclub is the devil’s temple; you’re going to find all the devil’s people in there.”

An undercover officer purchased marijuana at Club Hughes on September 22nd. As vice detectives closed in on the club, an announcement came over the PA system to alert patrons of the ensuing raid and urge the disposal of any weed.

A week later the undercover officer bought marijuana and Ecstasy in the club — more of the same a week later, including underage consumption of alcohol and “marijuana was being smoked freely inside.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

A temporary injunction was issued October 25th and the club’s doors and windows were boarded up. Hughes goes back to court December 13th to show, as he says, “everything that was Club Hughes is dead.”

Hughes says that a new business, “Hughes Uptown: The Restaurant Nightclub,” will rise from the ashes.

“I’m gonna change the color of the building,” he says. “I changed the security guards. They told me [in court] I can advertise, and I put a sign up that said we’re coming back, and the police tore that down.”

Hughes wants to make more changes to comply with court orders but won’t be able to until he can access the property again.

“I got a security system, same kind they have at the courthouse, a walk-through metal detector. When I went to court, I had all my ducks in a row. I wanted to show Judge Pollard. There were a lot of things that I learned about through the undercover investigation that I didn’t know. I didn’t know guys were selling dope. I wasn’t the one smoking or selling,” he says.

Finally, Hughes claims that the law is using his past against him. His 1991 conviction for sale of a controlled substance appears in the state’s petition to close Hughes down.

Hughes was, according to his own description, a “crackhead” at the time but has rehabilitated after several attempts and professes 12 years of cleanliness from crack and other substances.

“I think it’s got to do with my popularity. People talk about how they’re going to fill the courtroom when I go to court. I’ll probably have a couple hundred people down there,” he says.

Hopefully the fire marshal will be free that day.

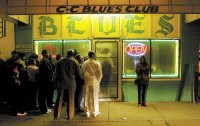

Hughes’ competitor, L.D. Conley, runs three nightclubs on Thomas, including CC Blues Club and LD’s Lounge up the street from Hughes. Conley’s Club Pisces is located farther north at 3987 Thomas. All three are painted in green and gold — L.D.’s a Packers fan — and CC features some of the finest exterior artwork anywhere in the city, courtesy of the mysterious itinerant sign painter known as Zorro.

Inside, Conley generously applies an old trick in the nightclub owner’s book: mirrors. They make the club and the crowd look huge.

“At CC,” he says, “I don’t remember a fight being here since I opened. I got rules in my club.”

One of the rules is a minimum age of 28 to enter. “That one helps a lot,” Conley says. “I’ll bend a little for 25, but not under. I know most of my customers.”

On a Saturday night, the MC tells the crowds it’s “grown and sexy.”

Conley opened LD’s Lounge as a restaurant in 1992. He converted the business into a nightclub after selling plate lunches for a while.

Conley opened CC Blues Club in 2002 and has showcased live acts such as Little Milton, Denise LaSalle, Sheba Potts-Wright, J. Blackfoot, and O.B. Buchana.

“You name it, they’ve been here,” he says.

On nights without such big-name entertainment, the house band ably fills in.

Conley says he’s “doing pretty good — making a living,” as a new black stretch limousine with gold embossed initials “L.D.” on its doors idles in the parking lot behind the club.

Conley plans to expand on CC Blues Club, which attracts a clientele from throughout the tri-state area. “Most of them are black, but I get a lot of mixed people from Beale Street, too. They ask [around] about blues clubs, and somebody down there sends them to CC.”

Conley recognizes similarities between Beale and Thomas and would like to see more.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“I wish they would do Thomas like they do Beale, so we could stay open all night,” he says. “Back in the 1960s, Thomas was Beale Street. We had more clubs and cafes.”

Colorful characters like Eugenia and Cadillac Willy ran neighborhood joints, while Johnnie Currie’s Club Tropicana hosted big-name rhythm and blues acts. Conley distinguishes a nightclub from a juke joint by the class of the building and sees his place continuing the Thomas Street tradition of Club Tropicana and the Manhattan Club, bringing upscale entertainment to a fine venue with “no spit-buckets on the floor.”

“I like to make people happy and see people enjoy themselves,” Conley says.

Unlike Beale in the 1960s, the locals on Thomas today see development — it’s not called urban renewal anymore — headed their way, and they hope it arrives. Beale businessman Robert Henry, who died in 1978 after the Memphis Housing Authority’s bulldozers plowed the street of his dreams, commented in the late 1960s that what Beale really needed was “urban re-old-al.”

Like Warren Lewis, though, L.D. Conley welcomes the possibility that their section of Thomas Street might see Uptown develop farther north.

“I wish we could get this street looking like down where the projects were [Danny Thomas Boulevard], with a median strip with trees and lightposts,” Conley says.

“I wish it would come all the way up Thomas Street. That would be nice. We would be another Beale Street.”