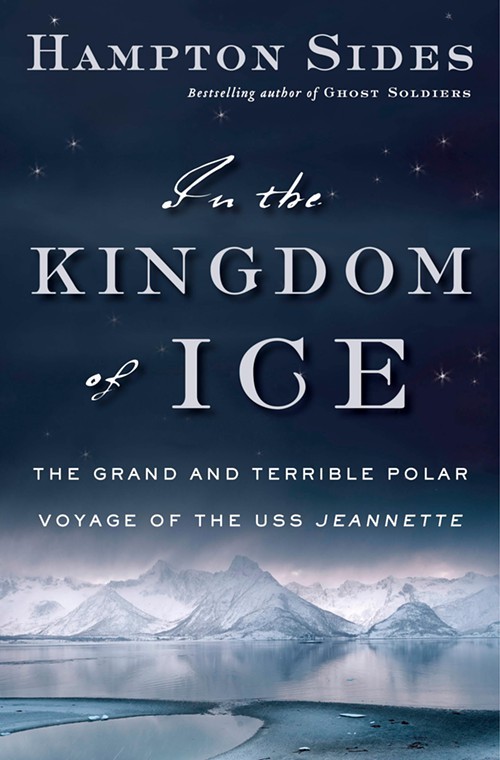

Turns out, this past Friday was a fine time to touch base with writer Hampton Sides, who’d just arrived in his hometown. In a few hours, he’d be discussing and signing his latest book, In the Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Polar Voyage of the USS Jeannette (Doubleday), at the Booksellers at Laurelwood, and he’d just received, in his words, “100 percent good reviews” in the 10 or so publications that had recently featured the book — publications such as The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and The New York Times. So: “So far, so good” Sides said by phone of the cross-country positive reaction. But for this native Memphian early into a book tour, Sides also said that it’s always good to be back in Memphis to see family and familiar faces.

[jump]

For those who don’t know about Sides’ latest book, see the writeup in the Flyer, and for those unfamiliar with the remarkable tale told in In the Kingdom of Ice, you’re not alone. Sides himself wasn’t familiar with the story (though it was world-famous in its day) before he set out to write of the voyage of the USS Jeannette. What follows: highlights from that phone interview on Friday.

Flyer: How did you come to write “In the Kingdom of Ice”? I’d never heard of the USS “Jeannette,” its voyage to the Arctic in 1879, or its captain, George Washington De Long.

Hampton Sides: I’d never heard of it either. Or of De Long. But I was in Oslo, writing a story for National Geographic about a Norwegian explorer named Fridtjof Nansen. He was obsessed with the Jeannette expedition, which happened about 20 years before Nansen’s own voyage to duplicate the Jeannette’s: get locked in the ice, drift for two years on the theory that he’d drift to the North Pole, and he came very close. And he survived.

Nansen’s ship, the Fram, is housed in an Oslo museum, and everywhere in that museum you see references to the Jeannette. I was like, what’s the Jeannette? I’m an American, never heard of it, never heard of George Washington De Long. Then I just filed it away, thinking this could be a good story. I didn’t know if there were survivors. I didn’t know the material I’d be working with. I got home, started tinkering, and went down this “ice hole” for four years.

The story felt right. The timing for this book was right. I love it when you can resurrect something that was once so well known and now forgotten instead of writing yet another book about, say, Lincoln or Teddy Roosevelt.

I’ve been interested in the Gilded Age and finding a story that shows the times — the outlandish characters, the enormous wealth, a big story influenced by just a few people. To me, the Jeannette expedition was a metaphor for the Gilded Age.

Were there previous histories of the expedition you could turn to?

Not many. The last book on the Jeannette was in the 1980s, written by a naval historian and published by the Naval Institute Press. Before that, there was a book that came out in the ’30s — a fictionalized account, a novel called Hell on Ice. Then you have to go back to the 1880s, to the original accounts. George Melville wrote a book called In the Lena Delta. De Long’s journal was published back then too and became a best-seller.

Arctic literature, though: There are so many books. I’d never paid much attention, and even now I’ve barely scratched the surface. And I’m not even talking about books on the South Pole. I read more for In the Kingdom of Ice than any other book I’ve done.

What did you hope to bring to the story that previous writers had not?

With these kinds of stories, the biggest task is to make the reader care about these individuals so that when things start going wrong, you care whether the characters live or die. In most of the accounts I read, you have little sense who these people were. So, I did genealogies. I dug up old newspaper accounts to make at least a handful of the characters come alive. If readers aren’t emotionally invested in the characters, the book won’t work. Readers won’t keep turning the pages. That was my biggest task.

Another thing: Early in my research, I found out about a relative of De Long’s, in Connecticut, who had a trunkful of letters in her attic — the kind of scenario that historians dream about. She was going to throw those letters away. I flew to Connecticut immediately and found the personal papers of De Long’s wife, Emma — letters to her husband in the Arctic, letters from their courtship days, photographs. That really made the story come alive for me.

And another thing, to answer your question: What could I bring to the story? For a long time, it was almost impossible for anyone to get to that part of Russia, Siberia, where part of the story takes place, because during the cold war that whole area around the Lena River delta was completely closed to the outside world. As far as I know, no American went there since the 1880s. So, when I went two years ago, it was possible to go where De Long and his crew went. I’ve written about that trip for Outside magazine, about my journey through the Bering Strait, through the Arctic, to the Lena River delta.

Sounds like the most travel you’ve done for any of your writings.

Most extensive by far, because so many of the elements to this story were scattered.

The expedition was predicated on an idea by German cartographer August Petermann, so I went to his hometown of Gotha in Germany. New York Herald Tribune publisher James Gordon Bennett Jr., meanwhile, was all over the Eastern seaboard of the U.S. but then mainly in Paris, where I visited the Tribune archives. (I could already tell that Bennett was going to be a really interesting character, to say the least.) And then I went to Siberia, about as far away as you can go.

It would have been easy if I’d just gone west from Alaska. Instead I had to go around the world, because there were about 20 permits I had to get, permits from Moscow. All this then, and all around the United States. So yeah, by far this is the most travel I’ve done for a book. Next time around, I’ll try something a little closer to home.

What was Siberia like?

It’s still extremely remote. The people are suspicious of you. They don’t know why you’d be coming there, because for centuries that’s where the Russian government sent people. It’s very bleak, and because it’s above the tree line, it’s tundra. I’ve never been anywhere like it.

But the people there know about the Jeannette expedition, and that was true throughout Russia. I went to villages where people said relatives had helped with the rescue. The main tribe is the Yakuts, and most of them don’t even speak Russian. But it was a really great trip. I went first to the east coast of Siberia, got on a Russian ice breaker, went to Wrangel Island after passing through the Bering Strait.

And the ice you saw?

I’m no expert by any means, but I did want to at least experience it once, get a feel for it. Ice entered into the book’s narrative in a lot of ways, so when I look at the book now, I’m like, yeah, the descriptions of the ice, the sounds, the whole feel of the Arctic … it’s a very special atmosphere that you can’t fake.

And this is a story that seems tailor-made for a film.

The whole story is cinematic, but the thing about filming in the Arctic is that earlier attempts have run into a problem … you know, all these men in furs start to look alike. You have to find a way to differentiate people. We’ll see where a possible film goes.

In the past, you’ve mentioned to me what you call “synthetic suffering” — individuals who nowadays test the limits of physical endurance, who perform spectacular stunts, for the adrenaline rush. How do you think they’d stand up to the rigors of a 19th-century sea voyage to discover the North Pole?

The Jeannette expedition was real suffering. But it’s amazing to me how many thousands of people signed up for it … applications from all over the U.S. and the world. People knew that this expedition was guaranteed to produce hardship and probably death, and it’s hard to imagine our current generation doing something like that. But we still have the exploring impulse, and the will to survive is in all of us. I just don’t think we’d be signing up now in droves for an expedition like the one headed by De Long.

At one point in “In the Kingdom of Ice” you bring up the ultimate irony: that by 2050 the Arctic ice cap, due to climate change, could in fact become an open sea, the very thing that De Long and his crew were hoping to find.

After talking to a bunch of climate people, 2050 is a safe date. But it will probably be before then. De Long set out in search an open polar sea that didn’t exist, but it may well exist, at least in the summertime, in the next 20 or 30 years. That is this story’s deep irony. •