Rehema Barber’s Director’s Choice exhibition at Power House,

“Everywhere, Nowhere, Somewhere,” packs multiple existential,

emotional, and visceral punches. Five talented local artists and six

nationally noted painters, sculptors, and videographers explore our

increasingly complex world and the often overwhelming sensory stimuli

flowing through its cell phones, cables, and cyberspace 24/7.

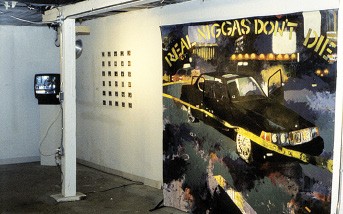

The words “Real Niggas Don’t Die” are hand-stenciled across the face

of RNDD: Tupac, Charles Huntley Nelson’s large acrylic painting

of the car in which Tupac Shakur was killed. Mounted nearby are

Polaroid images of tourists posing in front of the painting. The hollow

braggadocio of Nelson’s graffiti and the photo-ops of Tupac’s fans

suggest we are more titillated than moved by the death of this

multitalented rapper, actor, and philanthropist.

Red vinyl ribbons flow out of Joel Parsons’ 3-foot mound of latex,

acrylic, oranges, and incense work titled A Secret I Wouldn’t Know

How To Tell. In the exhibition’s most evocative site-specific

touch, the tattered ribbons cross the floor and trail into one of Power

House’s singed, crumbling furnaces.

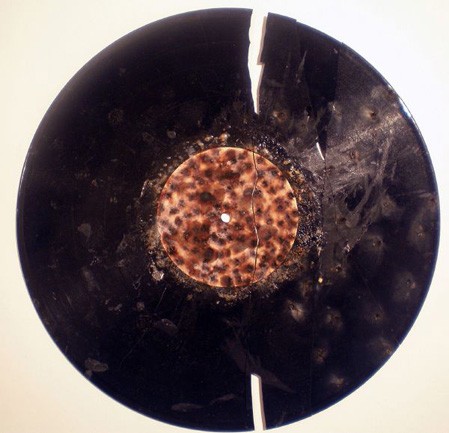

The rich textures and colors of Keith Anderson’s burned-and-broken

phonograph record As Africa Turns remind us that nature’s decay

can be beautiful. Anderson’s unorthodox and formally satisfying

sculpture is also richly metaphoric. As Africa Turns (as the

world turns, as the music industry turns) evokes royalties that have

been lost, African-American recording artists who have been burned, and

lives that have been broken by the world of entertainment.

Keith Anderson

Jack Dingo Ryan explores what happens when we stop listening to

ourselves and each other. At first glance, Ryan’s delicately fluted,

ivory-white polyurethane ears (hundreds of them) seem out of sync with

the work’s title, Blood and Guts Forever. By adding two

noticeably turned-off light switches to the piece, Ryan’s installation

becomes, in part, an unsettlingly original metaphor for what happens

when we stop communicating, stop valuing creative output, and, instead,

measure success with military power, including the time-honored

tradition of tallying battle kills with piles of severed ears.

The show’s allusions to Greek gods and biblical figures remind us

that the desire to make our mark and find our place in the world is an

ancient one. In Mary and Jonathan Postal’s montage of antique photos,

Vulcan Forging Wings, an African-American blacksmith forges

metal in his workshop next to images of a precariously tilted tenement

and a large bin of tires, worn-out and discarded like the blacksmith’s

ancestors who worked the plantations, chain gangs, and backbreaking

jobs of industry.

broken As AfricaTurns

The image of an African American just coming into his own as a

skilled artisan poignantly parallels Vulcan’s refusal to return to

Olympus to serve the gods, choosing instead to remain in the underworld

forging works of great beauty. Pigmented beeswax heightens the

intensity of the narrative. Sweat on the blacksmith’s nearly naked body

glistens. The red that oozes into the bottom of one of the iridescently

white wings looks as fresh as blood just spilled, somewhere in the

world, in the ongoing struggle for freedom.

The videos in the show provide important insights for understanding

and surviving our multicultural world. Tall, lean Massai warriors

dancing and models slinking along a catwalk in Brendan Fernandes’

digital video Aya Mama demonstrate humankind’s desire — in

every country and culture — to adorn itself, to strut its

stuff.

The two teenagers in Kambui Olujimi’s video Night Flight

create a room (or rooftop) of their own by rendezvousing in the middle

of the night on top of a Brooklyn apartment. They make their own music

and create their own dance steps as one of the teens, ebony body

swaying with boom box in hand, moves in tandem with

his fair-skinned roller-skating partner.

Dwayne Butcher’s digital video Partagas both lampoons and

pays homage to his redneck heritage. Instead of a hot tub, Butcher

mellows out in a makeshift pool in the back of his pickup drinking Dos

Equis and smoking fine cigars.

At one point in the video, Butcher places his feet flat on the bed

of his red truck, hoists his body, and pours golden liquid from two

cans of beer across his torso to the slow measured sounds of classical

music.

With his signature mix of stand-up comedy, confessional poetry, and

absurdist theater, Butcher describes his worldview in his artist’s

statement for the show:

“I think I will be okay as long as I can keep making digital videos

with the personality of a redneck hillbilly drinking beer naked in the

back of a truck.”