Hidden within a securely monitored, nondescript laboratory on the

University of Mississippi campus in Oxford lies a pothead’s dream come

true.

Heavy-duty cardboard barrels and boxes stored in a high-security

freezer hold pounds and pounds of marijuana buds. In the same freezer,

hundreds of rolled joints are stored in cans. In the climate-controlled

room next door, bright-green marijuana plants stand five feet tall, as

if ready for a High Times close-up.

Outside the Coy W. Waller Laboratory Complex, an empty field awaits

cuttings from those indoor plants, where at some time in the future, an

outdoor marijuana garden will flourish under the watchful eye of the

National Center for Natural Products Research’s Marijuana Project.

But this “dank” won’t be available for the bongs and pipes of Cheech

& Chong fans. The marijuana grown here is used strictly for

government-approved research purposes. In fact, the Marijuana Project

at Ole Miss is the only facility in the country legally allowed to grow

marijuana for research.

In its last growing season, in 2007, the university produced 400

kilos — around 880 pounds — for the National Institute on

Drug Abuse (NIDA).

In addition to growing pot for research, the Marijuana Project

analyzes samples of seized marijuana from all over the country. In

mid-May, Ole Miss released a report stating that illicitly produced

marijuana contains an average 10.1 percent of its active ingredient,

tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Compared with THC levels of around 1

percent in the 1970s and 4 percent in the early ’80s, today’s street

marijuana is more potent than ever.

Growing Government Pot

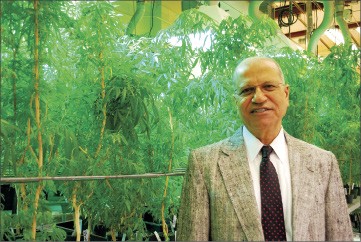

Inside a small darkroom, a set of grow lights are focused on a pair

of fully mature marijuana plants, boasting flowering buds and standing

well over the head of Dr. Mahmoud ElSohly, director of the university’s

pot-growing operations. The doctor gently rubs one of the buds and

smells his fingers.

“The smell is very strong,” says the mild-mannered director in a

heavy Egyptian accent. (In fact, with the large amount of marijuana

stored onsite, the entire Waller Complex has the skunk-like smell of a

stoner’s basement.)

Hundreds of other indoor plants in the grow room are kept alive in a

suspended state, meaning they’re not allowed to grow or bud, as a way

to preserve cuttings for the outdoor garden. This year, NIDA has yet to

request a large-scale outdoor “grow,” but when they do, cuttings from

the indoor plants will provide the starter material.

The Marijuana Project’s government contract from NIDA allows the

school to grow marijuana to be distributed for research across the

country. Marijuana is distributed to researchers after they’ve gone

through the proper channels with the Food and Drug Administration and

the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). For example, the National Eye

Institute has procured marijuana from Ole Miss to study the effects of

cannabinoids (the chemical components in marijuana) on intraocular

pressure.

“With marijuana being [a Schedule I drug], it’s only available to

investigators through the federal government. They’re the only entity

that can distribute marijuana, and they have possession of all the

marijuana that’s [legally] produced,” ElSohly says. “We are acting as

an arm of the

[U.S.] government.”

The Marijuana Project began in 1968, just a few years after THC was

discovered to be the active ingredient in marijuana. The federal

government was looking for standardized material to research, which

meant that marijuana would need to be grown under carefully controlled

conditions to regulate the amount of THC and other cannabinoids in the

finished product.

The federal government issued a request for proposals, and Ole Miss

was chosen for a three-year contract. The contract is renewed every

five years, and the university must submit a new bid each time.

“If another organization came along with equal capabilities that

could do this for a little less money, we could lose this,” ElSohly

says. “We have no idea who applies each time or even if anyone else

applies at all.”

But since the Marijuana Project has been housed at Ole Miss for more

than 40 years, it doesn’t seem likely they’ll lose the contract anytime

soon. ElSohly has been with the project since 1975, when he switched

from studying poison ivy to researching marijuana under the project’s

former director, Carlton Turner.

When Turner left to serve as President Ronald Reagan’s drug czar in

1980, ElSohly was promoted to oversee the growing operation, research,

and analysis of seized marijuana.

Bianca Phillips

Bianca Phillips

Dr. Mahmoud ElSohly oversees the Marijuana Project at Ole Miss.

Each year that NIDA makes a request for an outdoor grow, ElSohly and

his staff plant and tend the crop, followed by a harvest, and a drying,

manicuring, and de-seeding stage, before the marijuana is ready to be

granted to researchers.

After being tested for quality assurance, the pot is stored in a

large walk-in freezer maintained at a temperature of around 16 degrees.

Some pot is shipped to be rolled into cigarettes and then sent back to

the Waller Complex to be distributed to researchers.

“The cigarettes are not made here, unless there’s a requirement for

high-potency material, which doesn’t lend itself to mechanized

production of cigarettes, because it gets resinous and gums the

machine. We use a small hand roller for that,” says ElSohly. “But if we

need them in bulk, like say 60,000 cigarettes, we have a subcontract

with a company in North Carolina.”

During growing seasons, the Marijuana Project sometimes employs Ole

Miss students to help weed (no pun intended) the garden and harvest the

finished product. One would assume a marijuana farm on a college campus

would lead to a few security issues, but ElSohly says that’s not the

case.

“The project has been here for a long time, and, of course, people

always want to know where it is and what we’re doing. But we haven’t

had a problem,” ElSohly says.

That’s likely due to the presence of security cameras in every nook

and cranny of the Waller Complex. The outdoor garden, surrounded by a

tall double fence topped with barbed wire, also is monitored by several

cameras. During the growing season, an armed guard perches in a

watchtower at the garden’s entrance.

courtesy of the nida marijuana project at the university of mississippi

courtesy of the nida marijuana project at the university of mississippi

Rolled joints are distributed to marijuana researchers across the country.

Search and Seizure

On the countertop in a stark white laboratory at the Waller Complex,

a white cardboard box holds numerous clear plastic packages, filed by

DEA case numbers.

ElSohly lifts a plastic pack from the box, revealing tight little

nuggets of what used to be some pot dealer’s prized “kine bud” (slang

for high-potency marijuana). Other packs reveal some

not-so-high-quality samples of what pot smokers refer to as “dirt

weed.”

Each package holds less than an ounce from various drug seizures

across the country.

“We receive confiscated materials from the DEA and state eradication

programs, and then we analyze them for potency, THC content, and other

cannabinoids,” ElSohly says. “We usually get somewhere between 2,000

and 4,000 seizures a year to analyze.”

Once pot is seized, samples are sent to one of eight DEA labs across

the country. ElSohly’s team makes requests for samples of available

products, including hashish and hash oil. A small amount of pot from

each batch is put through a process that creates a liquid marijuana

extract.

Inside the lab, a couple of female researchers in white lab coats

are sending tiny vials of liquid extract through a gas chromatography

machine. The machine analyzes each vial and produces a computer readout

of how much THC and other cannabinoids are present in the sample. This

is how the Marijuana Project recently determined the average 10 percent

THC levels in today’s illicit weed.

“It’s very important to know what kind of material is being consumed

around the country,” ElSohly says. “It’s an abused drug, so we need to

know what people are abusing. It’s important not only from a standpoint

of the health consequences but from a research standpoint.”

bianca phillips

bianca phillips

Small samples of seized marijuana are sent to Ole Miss for testing.

That’s because researchers must test marijuana with different

potencies to determine the effects on patients with varying levels of

THC tolerance.

ElSohly says it’s only natural that illicit marijuana is getting

stronger, since users grow more tolerant of its effects with repeated

use.

“The market demands higher potency all the time, and the

higher-potency marijuana is more expensive and creates less bulk,”

ElSohly says. “The producers have gotten more sophisticated in the way

they produce the drug and how they prepare the material for the

market.”

ElSohly explains that illegal growers increasingly favor a method

that only cultivates material from female marijuana plants, meaning

there are no seeds but only flowering buds. The buds hold the highest

concentration of THC.

In the Bum

In addition to sampling seized pot and producing marijuana for other

medical researchers, the Ole Miss Marijuana Project also has developed

a few THC-based medical products of its own. In the 1990s, ElSohly and

his team developed a new “bottom line” method to administer THC to

patients.

bianca phillips

bianca phillips

The THC suppository was designed as an alternative to oral THC-based

medication, such as Marinol (currently available in a gelatin capsule).

Though marijuana is not an FDA-approved medical treatment, THC has been

approved to treat nausea and stimulate appetite in cancer and AIDS

patients.

“It’s used when cancer patients are going through chemotherapy and

are having problems with nausea and vomiting, and it also has an

appetite-stimulating activity that helps AIDS patients experiencing

wasting syndrome,” ElSohly says.

But ElSohly says THC pills have some drawbacks, such as a higher

risk of psychological side effects after the chemical is metabolized in

the liver, an unavoidable consequence of the medication passing through

the stomach. Also, patients suffering from nausea run the risk of

throwing up the pill before it takes effect.

“The suppository came about because of those disadvantages,” ElSohly

says. “And also with the idea that a suppository is not abusable.

People won’t take a suppository just to get high.”

Administered rectally, the THC suppository doesn’t pass through the

liver and is less likely to produce a psychological high. Its medical

effects last 12 hours, much longer than the four-hour effectiveness of

Marinol. However, the THC suppository isn’t commercially available yet.

ElSohly says the formulation was licensed to a pharmaceutical company

in the ’90s, but it lost the funding to produce and market the

product.

“It’s up for grabs now, and we hope some company will eventually

take it on,” ElSohly says.

He’s also working on another THC drug with a transmucosal delivery

system, which means the patient absorbs the drug through their gums.

Similar to nicotine skin patches, the transmucosal patch adheres to the

space above the gumline inside the mouth. THC is delivered through the

skin.

Though 13 states have legalized medical pot — and Tennessee

state senator Beverly Marrero recently proposed a bill that would make

it legal in Tennessee — ElSohly says smoking marijuana isn’t the

best way to administer the drug to patients:

“In my opinion, that’s just smoking the drug to get an effect.

That’s not a good pharmaceutical way to administer a drug, for obvious

reasons.”

In states such as California and New Mexico, some medical marijuana

patients may grow their own plants for personal use.

But as more states debate decriminalizing medical marijuana, the

cultivation and research at Marijuana Project at Ole Miss moves

forward, high above the fray.