We need more new plays. Good plays, terrible plays, mediocre plays, musicals, comedies, dramas, campy TV show adaptations and so on. I don’t really care what kind of plays they are as long as they are new and everywhere. We need them in experimental theaters, institutional theaters, on street corners, in shop fronts, living rooms, on the Internet, and hovering near the top of everybody’s to-do list. New work is what makes theater exciting. Nothing makes developing playwrights better than the experience of production at various levels. It’s good for emerging directors, and a special challenge for actors. New work defines theater communities and makes them stronger.

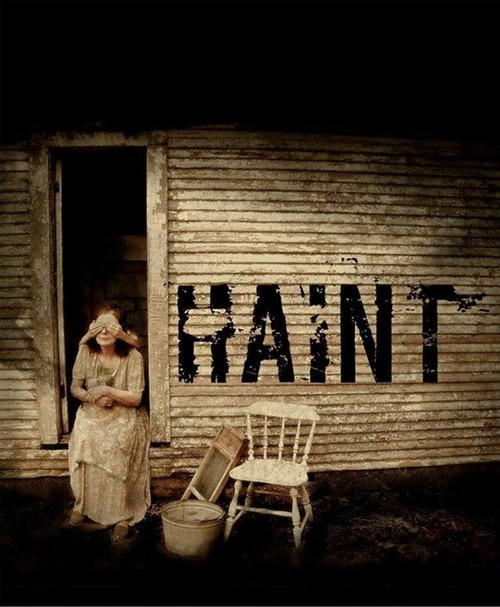

Haint, a new and promising play by Memphian Justin Asher, has been given a lush, richly-detailed debut by director Leigh Ann Evans, the New Moon Theatre Company, and a strong cast of Memphis A-listers. The result is an impressive, if uneven night of homegrown Gothic goodness. Ironically, for a show about a woman who loses her child under mysterious circumstances, “Kill your babies,” is the best advice I can offer the playwright. And I sincerely hope to see the play produced again—and soon— by a more impartial group, with a single aim: ruthless tightening. There’s one doozy of a 90-minute Jim Thompson (meets George Saunders) noir hiding inside a two and a half hour show puffed up with southern imagery and showy monologues all sounding too much like Memphissippi actor/playwright Jerre Dye riffing off Tennessee Williams’ Glass Menagerie.

Memphis audiences probably know Asher as the extremely tall singing and (reluctantly) dancing actor who played the monster in Young Frankenstein, stood in for William Holden in the musical adaptation of Sunset Blvd, and who, more recently, directed Germantown Community Theatre’s production of Twelfth Night. Haint is a strong first playwriting effort, inspired by a grandfather’s ghost stories. For those keeping count, that makes Asher a quintuple threat, and an artist to watch.

Although Haint’s prose occasionally drifts toward the purple end of the spectrum, and certain outcomes seem inevitable, it’s still an intriguing tale loosely modeled from stories about a woman wandering the highway looking for her lost son. Janie Paris, an always powerful on-stage presence, plays Mercy Seer, a caustic medicine woman and midwife who whips up weed-and-seed home remedies, hangs jars full of memories on trees, and occasionally pretends to talk to spirits for the townsfolk in order to pick up a few extra bucks. She lives on the edge of town with her son Charlie, who dies but never goes away.

Sometimes age matters, and Steven Burk is too young for the role of Sheriff John Thomas Dourghty, a decent-seeming fellow with marital problems, a taste for booze, and a dark, depressive side he mostly keeps hidden. But Burk is a reliable performer, and fully committed in the role. He gives one of his best performances. He’s paired with an equally strong Aliza Moran who plays his wife Evangeline, a struggling young mother who has never lost the reputation she acquired for youthful—and maybe not so youthful— indiscretions.

Randi Sluder takes to the role of Miriam Jessup like a duck to water. Jessup is a comparatively wealthy and influential busybody who aims to score big when highway expansion brings opportunity to town. She has some of the play’s best lines and some of its worst, as she lists in the direction of a Scooby Doo villain. Through it all, Sluder’s spot-on performance keeps things believable, even when the part becomes predictable.

Haint is fun because it brings together elements of rural noir, classic ghost stories, Southern family drama, and sews it all up with dark, disarming comedy. The pieces, which could easily be blown apart by too many windy Tom Wingfield-like flourishes, are held together by Leigh Ann Evans’ invisible direction and Chris Sterling’s highly functional, and fantastically detailed set.

Did I mention that we need more new plays? Because we do. That point was driven home when I left TheatreWorks and turned East toward the new Hattiloo Theatre, a thoughtfully-imagined new venue with deep roots. I first met the Hattiloo’s founder, Ekundayo Bandele, when he was staging I Remember Ghost, a collection of his own original plays in a second hand clothing store on Madison Ave. We need as much of that as we can get, and in spite of any complaints leveled here, Haint is the kind of play that can, and should inspire other artists to sit down to the keyboard and bleed.

Slow clap.

More details here.