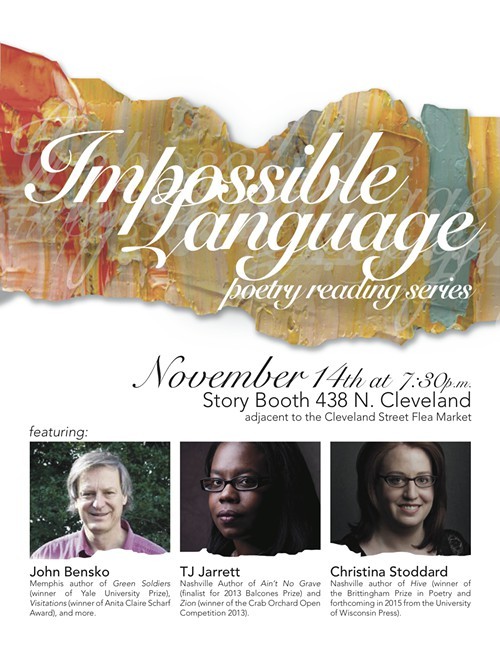

Poet Ashley Roach was right. When she referred in an email last week to the rainy, chilly day Memphis was having, she called it “definitely reading weather.” Friday night’s forecast for freezing temperatures makes it real reading weather. And John Bensko, TJ Jarrett, and Christina Stoddard will be doing just that: reading their own poetry on November 14th beginning at 7:30 p.m. at Story Booth (438 N. Cleveland).

[jump]

The event is part of the Impossible Language poetry reading series, which is spearheaded by Roach, who added in her email that Memphis poet Heather Dobbins has been instrumental in bringing these three writers to Story Booth.

Jarrett, who lives in Nashville, is a senior editor at Tupelo Quarterly and author most recently of Zion (Southern Illinois University Press), a collection that recalls 1960s Mississippi and her family’s ties to the civil rights movement. Stoddard also lives in Nashville and is an associate editor at Tupelo Quarterly. Her debut collection, Hive (University of Wisconsin Press), is scheduled to appear in the spring and addresses issues of religious belief — the faith in question: Mormonism.

There should be no need to introduce John Bensko to local readers and writing students: He teaches (along with his wife, the fiction writer Cary Holladay) at the University of Memphis. He’s the author of the short-story collection Sea Dogs. His debut poetry collection, Green Soldiers (1981), was winner of the Yale Series of Younger Poets prize. And his latest collection, published earlier this year, is called Visitations (University of Tampa Press).

It’s where we find Bensko revisiting the wounded of the Civil War and some of America’s 19th-century painters and writers. And though the sea may be “the oldest home we know” (in Bensko’s poem “To the Ocean”), it’s the landscape — plant life, animal life, throughout the seasons — that has drawn Bensko’s greater attention.

Frost is still on the window pane in late spring in “At Concord,” and illness is in the air in “Yellow Fever: Holly Springs, Mississippi, September 1878.”

It’s hanging time for the Confederate commander at Andersonville in “Henry Wirz, November 1865.” Autumn is candle-making time in “Bayberry.” And it’s cold at hog-killing time in “November Frost.”

More than frost, the waters of Niagara Falls have turned ice-solid in “Niagara: Winter 1878,” but “Snow Day” means more than a break in routine. It leads Bensko to meditate on that final break, not in routine but from life as we know it. What do we know of death? Disappearance, but what of us remains, what do we become, and what does the soul — should the afterlife exist — awaken to? The poet can’t answer. Enough that he raises the questions. And is it too much to ask that Bensko read the somber but lovely “Snow Day” at Impossible Language on Friday night, when snow just might be in the nighttime air? •