I’ve got a knack for blocking out distractions, but every now and then, one small thing can keep me from fully engaging with a play. In the case of Gem of the Ocean, I couldn’t figure out how a second story door leading to interior rooms might sit above a door leading outside, flanked by exterior windows up and down. Wilhelm screams were anticipated when characters passed the upper story threshold but, to my surprise, nobody fell to certain injury. I suppose it can be chalked up to an enduring truth about August Wilson’s problem play, Gem of the Ocean: 1839 Wylie is a house of mystery, where the veil of spacetime is thin. This is where Aunt Ester, the old home’s ancient inhabitant, transports pilgrims to an even more ancient city of bones. Nothing is normal here, and everything is.

Gem’s a fascinating work, packed with enough symbolism and code to build a Dan Brown novel around. It’s the chronological beginning to Wilson’s century-spanning, 10-play Pittsburgh cycle introducing audiences to vivid characters, and situations of shocking currency. Like a set with doors to nowhere, it’s also something of a jumble, and probably the most difficult and daunting piece in Wilson’s 20th-Century puzzle.

Gem is a family tragedy that aims to redefine family. The people living in Aunt Ester’s house aren’t related, but they rely on one another like blood. The only true kin in this story of law, order, peace, mayhem and a status quo looming like Armageddon, are Black Mary and her brother Caesar. She cooks for Ester in a poor but peaceful, charitable house. He wears a badge and relishes his role enforcing white interests.

Enter Citizen, a man with a secret, and a powerful need for soul-washing. Everybody told him to go to 1839 Wylie — a place of refuge and sanctuary. Times are so uncertain, and perilous for African-Americans there’s good reason to carry a heavy walking stick. There’s even debate over the relative merits of slavery, and the inevitability of prison. A man is dead because he was accused of stealing a bucket of nails from the mill. The man swore he was innocent, jumped in the river, and never came out — better free and dead than jailed for nothing. Before the show’s over the mill will be on fire and Aunt Ester, born at the dawn of the North American slave trade, will be in bondage once again.

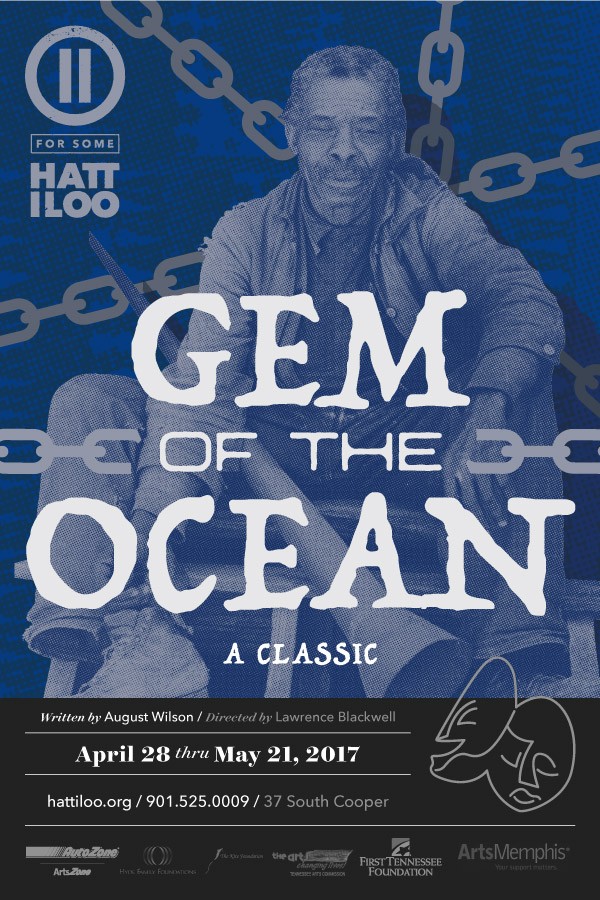

As mentioned, the Hattiloo’s Gem has issues, but director Lawrence Blackwell’s production succeeds in ways an earlier production at Playhouse on the Square didn’t. The key difference is intimacy. A perfectly cast ensemble makes the audience feel like we’re all seated around the table together while Black Mary makes a pot of greens. When everything turns to blood and sweat and chaos, the sense of alarm and disruption is shared.

Speaking of, when this Gem cooks, it really cooks, but to contradict Aunt Ester’s constant advice to simmer down, somebody needs to turn the heat up and keep it up. This play’s a slow burn in any case. Fumbled cues and lost lines can make a long play feel like bottled eternity. No bones about it.