Alfred Thompson Bricher’s Twilight in the Wilderness (1865)

Bold, Cautious, True: Walt Whitman and American Art of the Civil War

Era,” the tremendously moving exhibition at the Dixon Gallery and

Gardens, is not a blockbuster. It’s a slow burn, the kind of burn that

incises heart and mind with images of civil war.

Dixon director Kevin Sharp wrote the catalog and curated the show,

which includes paintings, prints, and sculptures on loan from such

prestigious museums as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Museum of Fine Art, Boston, and

the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburg.

Sharp weaves Walt Whitman’s poetry, Abraham Lincoln’s oratory, and

some of the most significant artworks created by mid-19th century

Americans into a compelling study of how a country torn apart by

slavery, secession, and civil war was able to survive and rebuild.

Acts of great courage and great crassness became the norm as

millions of Africans were enslaved and brother fought brother. A

wealthy landowner sells his mixed-blood son in Thomas Satterwhite

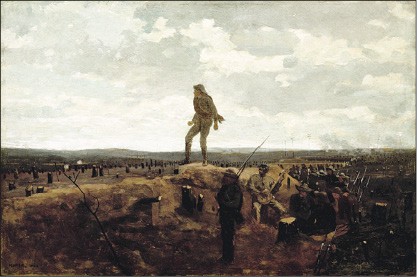

Noble’s The Price of Blood. In Winslow Homer’s oil on panel

Defiance: Inviting a Shot Before Petersburg, a Confederate

soldier, driven to distraction by carnage and the South’s impending

defeat, climbs the ramparts, clinches his fists, and offers himself up

as easy prey for Union sharpshooters.

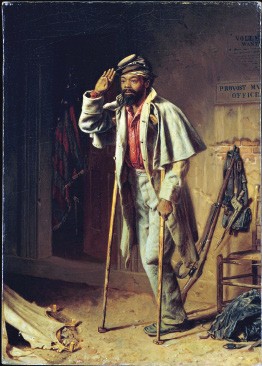

One of three panels in Thomas Waterman Wood’s triptych A Bit of War History: The Contraband, The Recruit, and The Veteran (1866)

In the triptych A Bit of War History, Thomas Waterman Wood

paints a man as a runaway slave, a soldier, and a disabled veteran

whose left leg has been amputated. The man’s unwavering look of

gratitude, in all three paintings, is unnerving until we consider that

this former slave’s life is now filled with memories of a daring escape

to freedom, patriotic service, and the camaraderie of fellow soldiers

instead of endless, back-breaking labor.

Winslow Homer’s Defiance: Inviting a Shot Before Petersburg (1864), on loan to the Dixon for the exhibit ‘Bold, Cautious, True: Walt Whitman and American Art of the Civil War Era’

By the end of the war, all pretense and dross has burned away. We

see it in the posture of a soldier, lanky and no longer young, who

leans on his rifle next to his ruined mountain home in Henry Mosler’s

painting The Lost Cause. We hear it in “Oh Captain, My Captain,”

Walt Whitman’s outpouring of grief for a president who saw his country

through the war but did not live long enough to celebrate the victory.

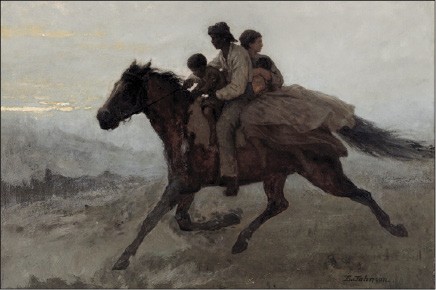

And, although we can barely make out the figures on horseback in

Eastman Johnson’s A Ride for Liberty — The Fugitive

Slaves, we can feel their intense focus as a mother, father, boy,

and infant girl race across the countryside, getting as close to

freedom as they can by dawn.

Many of the other artists in the show had their aesthetic

sensibilities honed by war and created their most fully realized

artworks after 1864.

Eastman Johnson’s A Ride for Liberty — The Fugitive Slaves, March 2, 1862 (1862)

In Alfred Thompson Bricher’s 1865 painting Twilight in the

Wilderness, a setting sun lights the underside of a cloudbank with

what look like a series of small fires. Bricher repeats his touches of

red-gold in fall foliage and a small campfire that warms two women.

Twilight in the Wilderness is not as luminous as landscapes

painted by artists of the Hudson River School before the war. But the

ground isn’t frozen and the sky blanketed with red, as in Louis

Mignot’s Sunset, Winter, a painting that conjures up the harsh

conditions, intense emotions, and bloodshed of war. There is, instead,

just enough warmth and light in Bricher’s work to allow the

unaccompanied young women, widowed or orphaned perhaps by the war, to

begin to make sense of things, to go on with their lives.