Jimmy Connors was grit and grind before grit and grind was cool in Memphis.

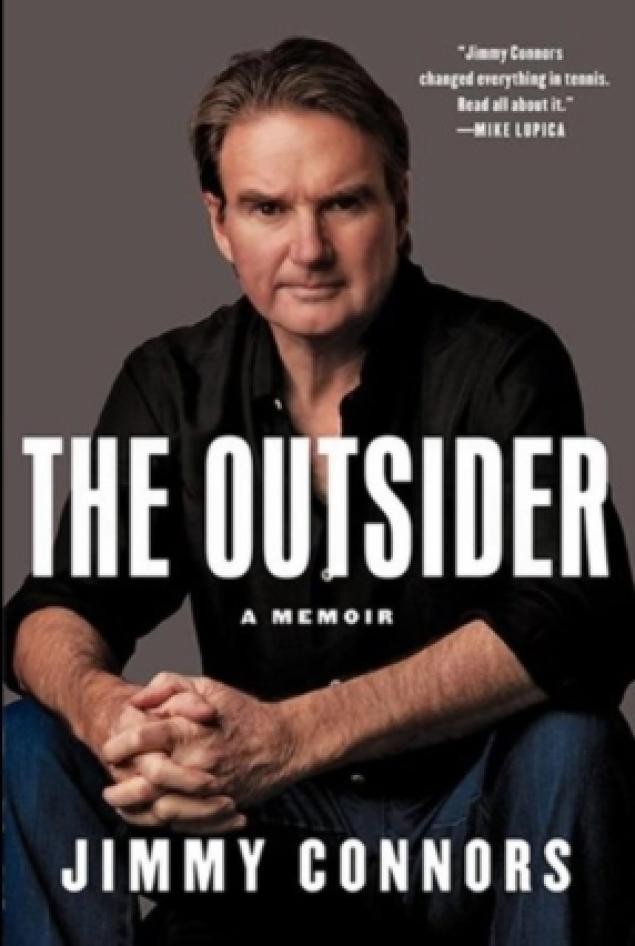

“For me there is only one way to play tennis,” Connors says in his new memoir “The Outsider.” “You put yourself on the line and fight to win, always. No questions asked. No compromise.”

No one who saw Connors play at the Racquet Club in the 1980s would disagree. He was the biggest draw the tournament has ever had, and nobody got the crowd into the match more than Connors with his fist pumps, arguments with linesmen and umpires, and memorable leap of the net to assist fallen opponent Henri LeConte in one final.

“The fans made every broken bone, every knee operation, every wrist operation, every torn muscle, every aching back and all three hip operations worth it,” he writes. “The fans won me more matches than I won myself. I fed off their energy and I never for a moment took them for granted.”

He won the tournament in Memphis in 1979, 1983, and 1984. He retired due to an injury in the finals in 1987, but nobody’s perfect.

Certainly not Connors, as he admits, and admits again ad nauseum even as he defends himself in this memoir. Not as a player, not as a husband, not as Chris Evert’s boyfriend, and not as a public figure.

The first time I saw Connors play was in the national under-16s at Kalamazoo. He was from near East St. Louis, the wrong side of the river if not the tracks. No collared white shirt for him, like the country club kids he thrashed. He wore a plain old t-shirt.

My view of Jimmy Connors is influenced by an old friend, the late Memphis tennis pro Derrick Barton, who played at Wimbledon in the 1940s. Derrick was an old-school British gentleman and said simply that Connors and Ilie Nastase nearly ruined the sport with their antics. Other friends were linesmen for Connors matches at The Racquet Club. “Do you know what ‘you suck’ means?” he hissed to a woman linesman by way of disagreement with her call. Takes a hell of a man to insult a woman who can’t talk back.

But we watched him, talked about him, wrote about him because he was Jimmy Connors. And if the alternative was Stefan Edberg or Pete Sampras or Kevin Curren, it was an easy call. Connors understood that sports fans not only don’t care about personal foibles, they like a villain more than a Boy Scout. Readers of this book probably feel the same way, me included.