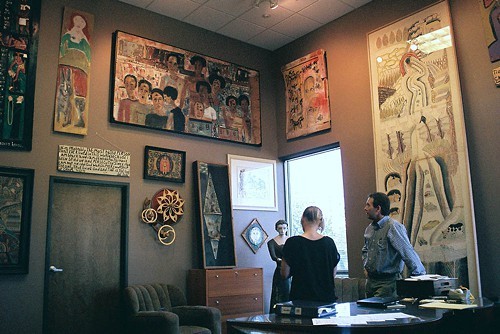

Memphis art collector and business owner John Jerit has one of the most unusual collections of art in the country.

Jerit, whose company American Paper Optics, has a corner on the 3-D paper glasses manufacturing market, collects folk art. A lot of folk art— enough to cover the 20-ft high walls of his Bartlett office, to fill a large Memphis home, and to occupy several storage units.

“Folk art” is a blanket term for Jerit’s collection. More correctly, he collects work by self-taught, visionary or outsider artists. It includes memory works (paintings based on artists’ memories rather than observation), wood carvings, tramp sculpture, trench art and handmade circus paraphernalia. A large part of the work is Southern, though some is from other corners of the country. A small amount is European.

Housed in this collection, alongside works that Jerit purchased for as little as a couple hundred dollars, are works by Henry Darger and Martin Ramirez. Darger and Ramirez are two of the best-loved (and, for a collector, most-sought) self-taught artists.

Images: Brett Hanover

[jump]

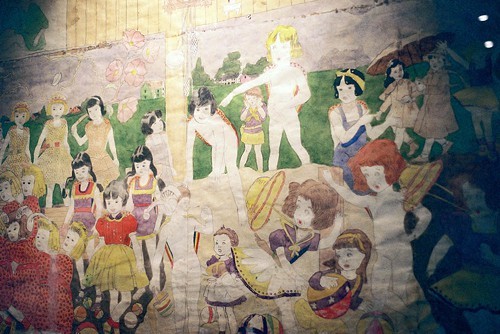

Henry Darger is the late author of the purported “longest book ever written,” a 15,145-page tome called The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion. He lived hermetically and worked constantly, in time producing not just the novel but hundreds of wall-sized watercolor illustrations of his dreamt world. The characters that people his illustrations were roughly traced from publications and composed by Darger into dense, graphic scenes. Jerit calls his Darger, a long narrative scroll, “a tame one.” In it, deathly pale children walk across a lawn, devils speak, and lightning strikes.

Martin Ramirez’s work is known for its undulating lines and fantastically illustrated animals. Ramirez’s drawings are almost psychotropic. He used a bland palette paired with brutal repetitions of form, and executed his work on a large scale. His work, like Darger’s, was made with cheap paper and drawing tools, and, like Darger, Ramirez tended to draw on both sides of the paper (Jerit says that, for display, he flips the pieces yearly.) Ramirez was a diagnosed schizophrenic who spent the entirety of his adult life in a California mental institution. Despite this, his work feels in touch with his generation: stark and modern at times, surreal at others.

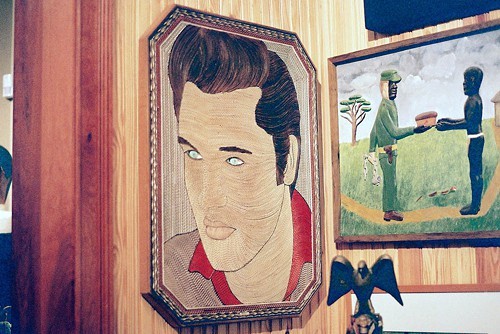

Jerit also collects Howard Finster, a Georgian pastor famous for peopling his paintings and sculptures with U.F.O.s, pop icons, and religious ephemera. Also featured: retired Memphis firefighter Edwin Jeffries, whose woodcarvings depict (variously) members of the Klu Klux Klan and dramatic Biblical scenes; French spiritualist painter Augustin Lesage; Charles Dellschau, visionary designer of imaginary aircraft; Minnie Evans, who managed to create striking portraits using crayons. The list goes on.

The collection’s aggregation has taken Jerit a decade of concerted effort. Before he collected folk art, he collected propaganda posters, and before that, “It was always something.” His interest in self-taught artists was partially inspired by a 2004 University of Memphis show called “Coming Home.” The show was curated by Professor Carol Crown, author of book about Southern self-taught and folk arts.

Though Jerit’s collection is broader than just regional arts, he acknowledges that Memphis is a good place to be for a collector of his bent.

The work self-taught artists can be controversial (fine arts critics often say the work doesn’t participate in a larger artistic conversation), but it is undeniably part of the lifeblood of Southern arts. It is easy to see that history when viewing Jerit’s collection, whether it is carved in wood, painted on planks, or scrawled on a canvas.