I have a theory about reality television.

I have a lot of theories, and if you ever meet me and don’t move fast enough, I’ll tell you about them. Here’s my theory of reality television: It’s representative of the way television producers see the world. The scourge of reality television as we know it today began with The Real World in 1992, when two MTV producers who set out to do a youth-oriented soap opera like Beverley Hills 90210 decided they didn’t want to pay writers. What are TV shows, after all, but attractive young people standing in front of cameras, saying words? The producers never really understood what value writers or actors or costumers added to the product of attractive people standing in front of cameras saying words, and they bet no one else did, either.

They were not entirely wrong. In fact, since The Real World has run almost as long as The Simpsons, (which cost exponentially more to produce), you could say they were entirely correct in their assumption that putting nonunion attractive people in front of a camera and telling them to say something would fool audiences into thinking a television show was taking place. The audience accepted the rough edges, which were entirely the result of the producers’ cost cutting, as signs that what they were seeing was “real.” Conflict sells, but that can be contrived by manipulative editing. The more cynical the vision, the more successful the show. You could put any old loudmouth idiot on TV, such as the loudmouth joke of the New York tabloid press Donald Trump, and people would watch for the sheer perversity of it.

Similarly, the John Wick films are how stunt men see the world, and their product. Director Chad Stahelski broke into the business as a stunt man in The Crow. He was Keanu Reeves’ stunt double in The Matrix trilogy, so when he pitched his film idea about a retired assassin who starts killing people because someone stole his car and killed his dog, he had a star lined up. At least Stahelski understands the concept of character motivation.

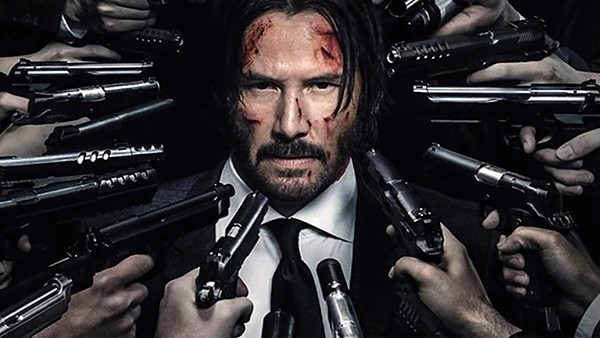

Keanu Reeves faces off against impossible odds in the fight choreographer’s dream that is John Wick: Chapter 3.

So how do fight choreographers understand films? Some boring talky parts getting in the way of the stuff that pays: pretending to fight. Now that we have progressed to the ungainly titled John Wick: Chapter 3 — Parabellum (A colon AND an em-dash — a punctuation lover’s dream!), they have almost dispensed with the boring parts where attractive people say words in front of the camera. And yet, the film has four credited writers (one of whom presumably did the punctuation), and a bloated 131-minute running time. The Real World producers would like a word.

No matter. John Wick would just kill them. The “story”picks up where John Wick: Chapter 2 left off. John Wick killed people for two hours, then was allowed an hour to escape justice by Winston (Ian McShane), the proprietor of the Hotel Continental, a secret base for a network of globe-trotting assassins called the High Table. Stahelski and his four writers have exactly one narrative trick up their sleeve: Start a clock counting down, then start another one. The more clocks ticking, the greater the tension!

Visually, though, Stahelski has a lot of tricks. The bloated contemporary James Bond films wish they had this kind of style. Since these are basically an Americanized wuxia movie, the fight choreography is the entire point. It’s structurally a dance picture. Add a tapping Jet or Shark, and Stahelski’s street fights become West Side Story. The climactic fight — a spectacular reimagining of Bruce Lee’s house of mirrors sequence from Enter the Dragon — is even kicked off by a literal needle drop.

It might sound like I’m being too cynical about a little slapstick gun fu. It’s all in good fun, right? The good stuff from The Matrix, done on the cheap. But at least the Wachowskis had an anime-inspired, pulp neo-Gnostic vision. Their message was for their audiences to look beyond the illusions thrown up by the powerful and “see things as they really are”; a world of oppressors and the oppressed playing out the same script over and over throughout history. John Wick is an amoral killer killing other killers who exist to serve only money and power. He operates in an authoritarian parody of the rule of law, where criminal oligarchs posing as hoteliers expect absolute fealty from their well-heeled murder servants. He goes on about “rules” and “consequences,” but the only rule here is might makes right. John Wick is the slick, empty, cruel hero the age of Trump deserves — but hey, at least he likes dogs!