I was really hyped to see Johnathan Robert Payne’s performance, ”Meet Me Where I’m At,” Friday night at Crosstown Arts. I’m glad I did.

I’ve loved Payne’s art since I first ran across it at Beige, where the artist had a solo show last fall. That show was made up of obsessive, abstract ballpoint pen drawings — all modular lines, meditatively blended. I’m a sucker for his pensive and lonely works on paper, which seem more about the repetitive process than the final product. They recall Alighiero Boetti’s intricate ballpoint pen pieces, as well as the strangely sloping linear drawings of folk artist Marin Ramirez. They feel to me like a removed headspace, rhythmically applied.

Which is partially why I was so curious about this show. How would Payne’s pensive, quiet style of making translate into performance?

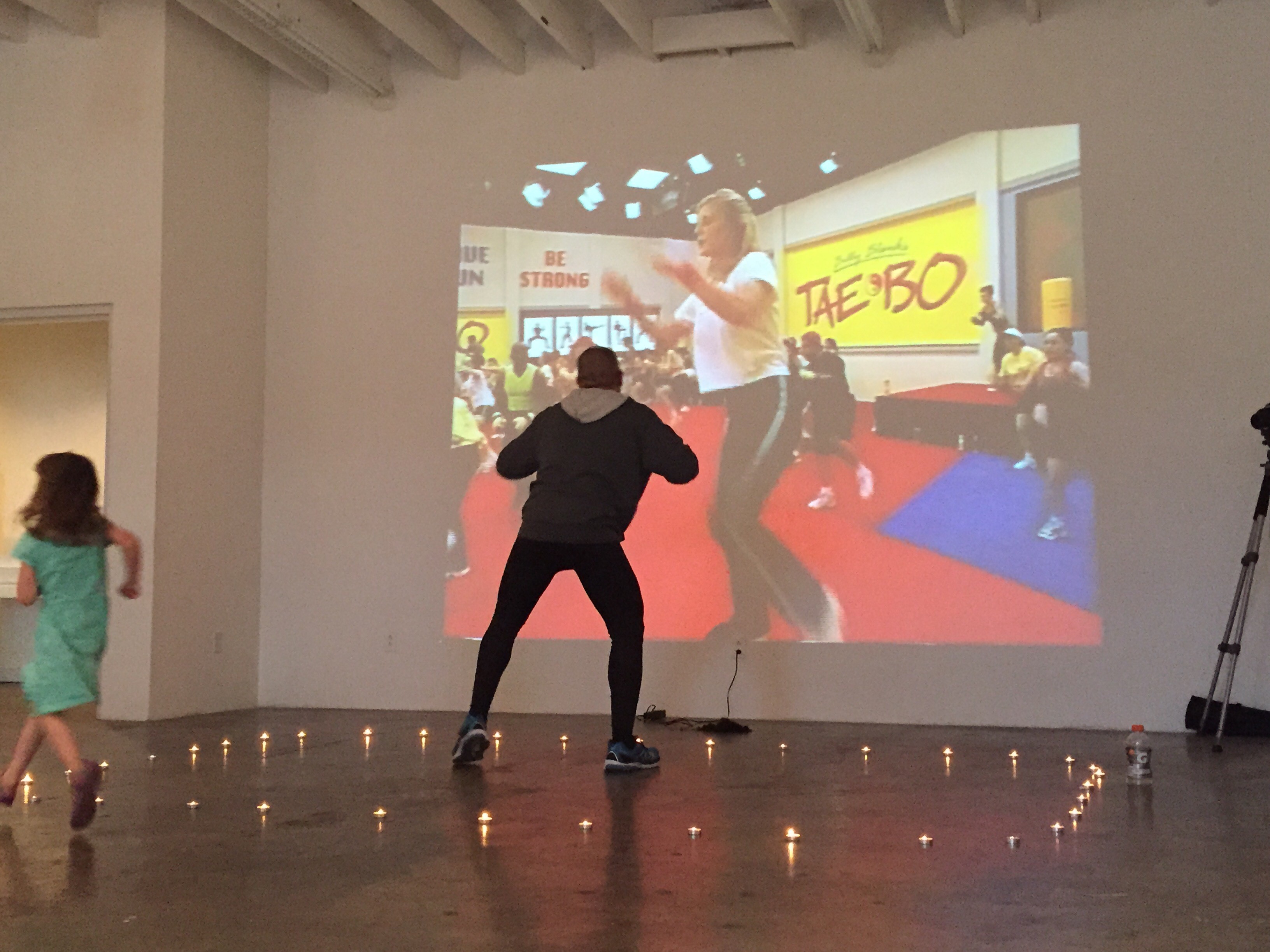

We were given 20 minutes between the show’s opening and the start of the performance to roam the gallery. Near the door, there were several curtains made of cut paper that Payne threaded together, fishnet style. A black, industrial tub full of water sat in the middle of the room. Several small drawings hung on the walls and, in one corner, a braided yarn rope dangled from the ceiling. Towards the back of the space, lit tea lights demarcated an 8ft x 5ft (est) rectangle on the ground. A projector lit up the far wall of the gallery, paused on a still frame from the opening sequence of Billy Blank’s Tae Bo Workout. The objects could have been the set-up for a joke: “A duck walks into a bar…”

Payne entered the space, kneeled facing the audience, and immediately shaved his beard and head. As he shaved his head, I became aware of what he was wearing: a grey hoodie, which suddenly took on a monastic glow. I also became aware of text on the paused screen behind him, a disclaimer that reminded us that Tae Bo is not a substitute for “counseling from your healthcare professional.” Payne then put on a pair of glasses and moved into the middle of the tealight-defined stage. The video started. For the next 50 minutes, he faced the back wall of Crosstown arts and did Tae Bo.

Payne was dwarfed by the screen, by Billy Blank’s huge projected visage. The scale of the projection reminded me of what it was like to watch Tae Bo commercials as a kid during endless, bored summers. Billy Blank instructs a crowd of fitness models on a red mat, backed up by graphic art of Billy Blank himself and a block lettered sign that reads “BE STRONG.”

Tae Bo, it turns out, is really difficult. Payne became visibly more exhausted as the video picked up speed. After 45 minutes had passed, the audience members who’d hung around that long started to cheer Payne on: “You got this!” or “Almost there!” Some of the Tae Bo moves were funny. Others were exposing. It was hypnotic. The bathtub loomed.

When the video finally ended, Payne sat down and turned towards the audience. He looked beat. He was a human again. I felt a wave of embarrassment, or guilt, or something. Payne then stripped down to his boxers and got in the bathtub. He submerged himself, then washed his whole body, carefully, with a bar of ivory soap. He didn’t acknowledge us.

He got out of the bathtub, still wet, and began to pick up small fortune cookie fortunes that, I realized, had been floating in the water. For the first time, Payne looked at us, and read: “Now is the time to investigate new possibilities with friends.” He then picked up another object — a pink funnel attached to a pink tube, beer bong style — and filled it with the fortune and soapy bathwater. For a moment, I thought he was going to offer it to us to drink.

Instead, he turned the action on himself. He attempted to swallow the water, choked and spit up. He repeated this action with three more fortunes (“a distant friendship could begin to look more promising,” “you will take a pleasant journey to a place far away,” “you will soon have the opportunity to improve your finances”), circling the tub each time. Then he exited the room. Someone said: “Are we going to clap? That was pretty good, wasn’t it?” and everyone clapped.

Payne’s work is punishing, but not exactly cruel. Tae Bo is a lonely mortification to be followed by ablutions in a rubbermaid tub, to be followed by a spiel of Chinese fortunes (the food of lonely American cliche.) These are familiar, unthinking moments. Who hasn’t worked out alone, showered, and eaten take out?

The weirdness of performance art vs. theater is that, rather than removing you from your body with a fear of lighting and narrative, performance art more often than not makes you super conscious of it. Which might be Payne’s point: rinse, repeat, repeat, rinse, pay attention. Stay aware. We’re all lonely. Meet us where we’re at.