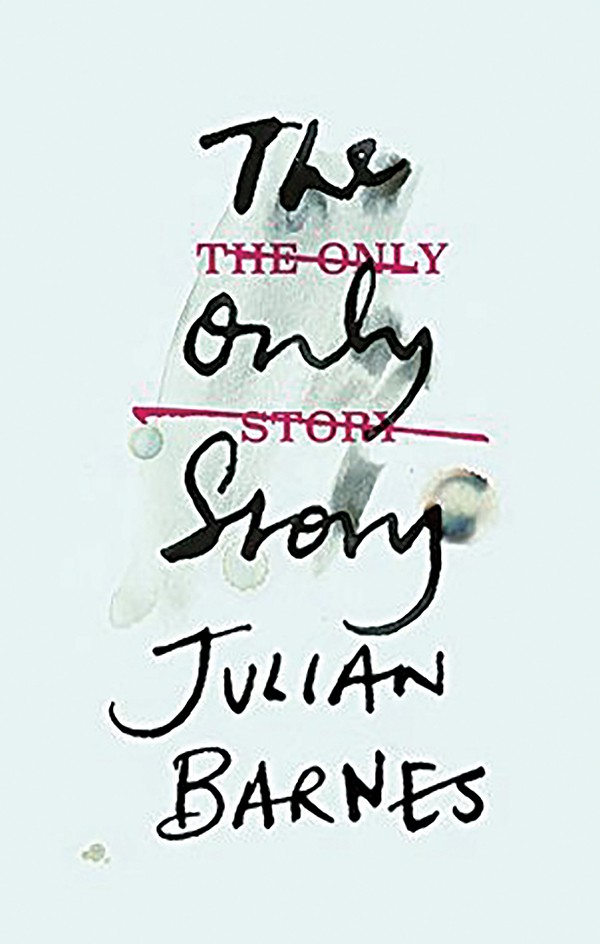

Julian Barnes became a household name — in bookish houses, of course — with his third novel, Flaubert’s Parrot. It’s a witty, crazy-quilt, postmodern meditation on reading and writing a novel, that is both literary and entertaining. Since then, he has gone from strength to strength — he won the Man Booker Prize for The Sense of an Ending — and The Only Story, his newest novel, is one of his best. Barnes is witty and urbane, pithy and highly readable, somewhat like his fellow countryman Ian McEwan. The Only Story is thoughtful and thought-provoking, with a depth of observation and analysis that, at times, seems Updikean.

It begins, “Most of us have only one story to tell. I don’t mean that only one thing happens to us in our lives: there are countless events, which we turn into countless stories. But there’s only one that matters, only one finally worth telling. This is mine.”

The story that follows is bittersweet, a sort of reverse Lolita tale — Paul is 19, Susan is 48 when they meet over country club tennis — told from Paul’s point of view, looking backward at what became much more than an immature indiscretion. The novel charts their course over decades. What begins in innocence — when Paul says he doesn’t have a reputation, Susan replies, “Oh dear. We’ll have to get you one then. Every young man should have a reputation” — becomes a tangle of emotions and responsibilities. The book’s essential question is, “How much do we owe the people who love us?” Barnes is wise and surgical in his examination of passion and its obligations. The Only Story cuts deep. It’s a dazzling, shrewd, painful consideration of who and what we are when we love.

Paul wants to take care of Susan, which includes protecting her from an abusive husband. He’s naïve, but she is ready to cede decision-making to someone else. Paul decides to become a lawyer, partly so that they will not have to live off her money. “I decided to become a solicitor. I had no exaggerated ambitions for myself; my exaggerated ambitions were all for love,” he says. Once the affair is begun, they do little to hide their amour, not even from Susan’s husband. Eventually, they are kicked out of the tennis club and the scandal — modest British opprobrium, of course — helps cement them together. They wear their outlaw colors as if a badge.

As with most chronicles of romantic relationships, fate enters in. Though this is Paul’s “one story,” it is a ragged affair, involving undying love, troublesome family members, unreal expectations, and, over time, a flux of emotions, all revealed by an unreliable narrator. The fantasy author, John Crowley, said, “Stories last longer, but only by becoming stories.” Paul says, “This is how I would remember it all if I could. But I can’t. There’s some stuff I left out… .” He admits that the story is told through his filters and no one else’s, and that the picture is distorted by his janky memory and by what he wants to include and what he wants to leave out. Between the lines, one senses that the hero of his story, himself, is not entirely without blame for the affair’s outcome.

The tale toggles back and forth between first person narration (by Paul) and second person (the “you” being Paul). “You have no theories of life yet, you only know some of its pleasures and pains. You still believe, however, in love, and in what love can do, how it can transform a life, indeed the lives of two people.” In this varying narration, is Paul distancing himself from the story, sloughing off the responsibility of being the protagonist? Is he asking, what would you have done? Eventually, like all stories perhaps, Paul’s narrative switches to third person. Eventually all memoirs become novels. “For instance,” the narrator takes over, “he thought he probably wouldn’t have sex again before he died. Probably. Possibly. Unless. But on balance, he thought not. Sex involved two people. Two persons, first person and second person: you and I, you and me. But nowadays the raucousness of the first person within him was stilled.”