Dinosaurs. We all love them and secretly wish to be eaten by one someday.

Steven Spielberg knows this universal truth, and so in 1993, he adapted Michael Crichton’s novel Jurassic Park into a classic film and used the money and clout its success brought to create his masterpiece Schindler’s List. But Jurassic Park was a landmark film for reasons beyond the boffo box office tally. It marked the coming-of-age of CGI, even if many of the most spectacular scenes were the practical work of special effects master Phil Tippett. It introduced the world to the latest thinking in paleontology: Not all dinos were cold-blooded and slow-moving, and they were the ancestors of birds. But best of all, it was a fantastic adventure film of the kind few people besides Spielberg can actually make work.

Colin Trevorrow, director of Jurassic World, is just the latest in a long line of directors who have tried and failed to reproduce the Spielberg touch. Perhaps the director, whose last film was the low-budget time-travel indie Safety Not Guaranteed, can console himself by rolling around on Brontosaurus-sized piles of money, but he shouldn’t feel too bad. Inviting comparisons with Spielberg is a fool’s game. Jurassic World is not a misfire, just a pale reflection of Jurassic Park.

The film opens with images of eggs hatching, a new generation of velociraptors to thrill and chill the attendees at Jurassic World, a theme park built on the site of the ill-fated original by vaguely Arabic rich guy Simon Masrani (Irrfan Khan). The very existence of Jurassic World is an example of the film’s basic problem: After the extraordinary carnage inflicted on paying customers by the dinos in the first film, who in their right mind would try to do it again? How would they even get insurance?

Let’s root for the dinosaurs: Jurassic World.

But this is a monster movie, so even as we follow brothers Zach and Gray Mitchell (Nick Robinson and Ty Simpkins) to the park, we know the insurance companies are about to take a major bath. The kids are being sent by their divorcing parents to visit their aunt Claire (Bryce Dallas Howard), a Jurassic World executive whose emotional responses are a low priority on her daily action list. We get to experience the wonders of the family dinosauria through the kids’ eyes while Claire shows her boss the park’s newest asset: a genetically engineered super-dino named Indominous Rex.

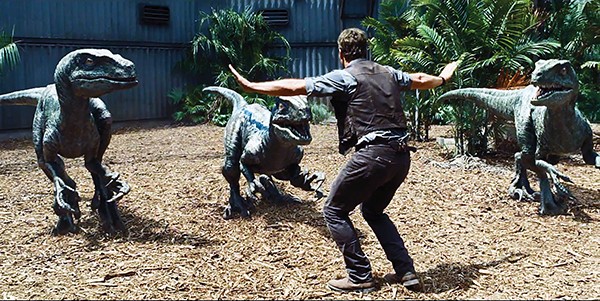

Reader, I know you’re wondering if we get to see Indominous fight a Tyrannosaurus. Of course we do. The thunder lizard action in Jurassic World is first-rate. There are old favorites, such as the peaceful herd of brontos that wander the volcanic island’s grassy plains. The series’ true stars, the velociraptors, are now the charges of dino whisperer Owen Grady (Chris Pratt), who has successfully trained a pack of them to regard him as their leader. When corporate security head Vic Hoskins (Vincent D’Onofrio) proposes weaponizing the ‘raptors, Grady, in a rare flash of common sense, tells him what a mind-numbingly stupid idea that is.

Maybe that, combined with Pratt’s easygoing manner, is why Grady is the only character in the film whom I was able to work up any sympathy for. The rest of the human cast are either ciphers, like the two kids who serve as audience surrogates, or actively repugnant. Claire, for example, is set up early as an unlikable corporate tool, and her character seems to learn nothing as she is repeatedly saved from bloody extinction by Grady. The audience I saw Jurassic World with cheered as one character after another got eaten by the dinosaurs.

But maybe the crappy characterization is a feature, not a bug. The production design and the CGI are first-rate, and the 3D work is the best I’ve seen since Avatar, a film Jurassic World borrows a couple of gags from. If all of the characters except Grady are intentionally drawn as insufferable jerks to make the dinosaurs more sympathetic, then bravo, mister director, you’ve succeeded. I don’t quite think that was Trevorrow’s intention, but I had fun rooting for the dinosaurs anyway.