When he’s not stitching up car seats at Reyes Customs, Enrique Reyes is busy stitching up colorful lucha libre Mexican wrestler masks. Reyes, 39, also puts together la lucha libre matches in Memphis.

Lucha libre, which means “free fight,” is the Mexican version of professional wrestling. “It started back in the 1930s,” Reyes says. “The difference is all the Spanish wrestlers use masks, like back in the days of the Aztecs, who also wore masks.”

The Mexican wrestling technique is different from American professional wrestling, Reyes says. “The Mexican wrestlers, they fly a lot. They don’t do like the American wrestlers. They do a lot of high-flying air moves.”

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Hijo de Fishman and Blue Angel

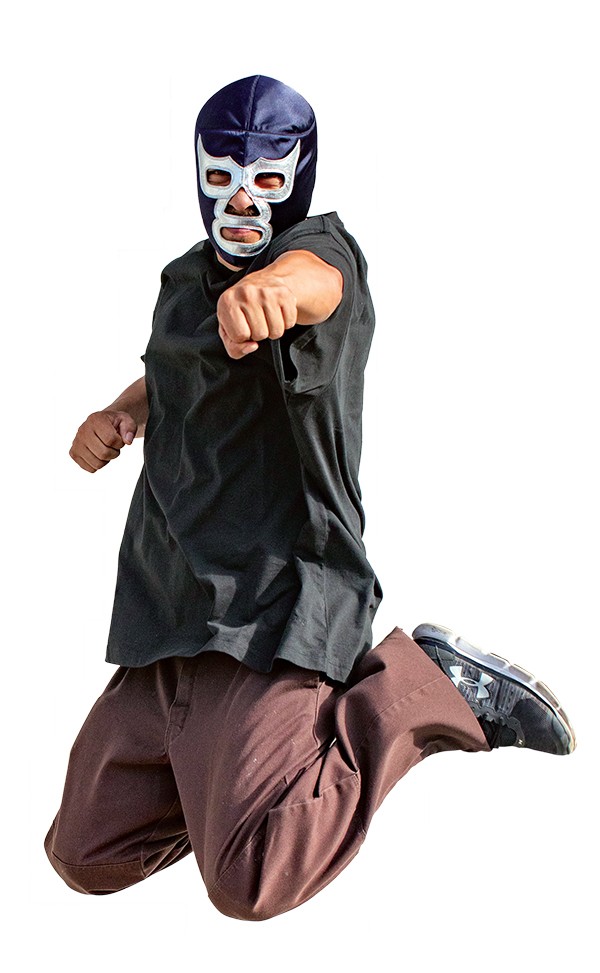

During a recent lucha libre event in Hickory Ridge Mall, enthralled members of the audience munched snack bar chicharrones between cheers, as masked wrestlers did back flips off the ropes and front flips off the mat. The obvious favorite was bare-chested Blue Angel, who wore blue tights and a blue mask with wings made by Reyes.

Asked what draws people to lucha libre, the Dallas-based Blue Angel, 30, says, “I believe it’s the pace. The flexibility of the match. The match can be either comedic — jokes and laughs — or it can be fast-paced and serious, very acrobatic. It’s always fun to watch.”

Blue Angel says he has a “very traditional style. I’ve incorporated some of the new-school with strong styles — little flips here, a little flip there — but I always keep it very basic old-school: a little ground work, a little air, a little bit of everything, just to keep it interesting.”

Blue Angel’s father wrestled in Mexico. “He came to the United States and started wrestling under ‘Blue Angel.’ So I grew up going and watching him wrestle with other great wrestlers. I’ve gotten to train with each one of them. And taking the good out of each one just by watching them and practicing with them in my father’s gym. I’ve been on the ring since I was 3 years old. And I think that’s one of the advantages that I have. That really helps me draw the crowd when I wrestle.”

His mask was one of several Reyes has made for him. “I started off with one of the local mask-makers down in Texas. The first time I came out to Memphis, Reyes took a liking to my mask. Then he designed a better mask, added a little of his style to it, and this is the result.”

Blue Angel says he likes the stitching in a Reyes mask. “It fits really well. It hugs my chin really tight. It’s a very clean, well-made mask.”

Reyes’ office and workshop at Reyes Customs — where his work ranges from window tinting to making car upholstery — is a shrine to lucha libre. About 100 masks line shelves on all four walls. Some are masks Reyes has made himself, and others are masks he has collected or been given.

Reyes’ interest in Mexican wrestling began when he was a child in Mexico City, watching lucha libre matches on Saturday morning TV. “The real heroes in those days — you’re talking about El Santo, Blue Demon, Rayo de Jalisco,” he says.

He bought comic books based on his wrestling heroes, but he couldn’t afford to go to live matches, which were a couple of hours from his home. “We didn’t have that type of money to go all the way to watch those types of shows,” Reyes says.

Blue Angel poses with a fan at a recent MLLW event.

His interest in lucha libre was rekindled when he began going to American wrestling matches after he moved to Memphis in 2001. “When I saw this, I said, ‘Damn. I need to start doing something.’ That was my dream when I was a kid — meet one of the big wrestlers like the Mexican luchadores.”

Tattoo, an American wrestler/promoter, helped Reyes get into wrestling promotion, but Atlantis, “one of the legends from Mexico,” was the first luchador Reyes contacted. “I found him on Facebook,” he says.

When Reyes told the wrestler he wanted to start doing some lucha libre shows, Atlantis said he’d come to Memphis to wrestle, but Reyes would have to pay for his flight and hotel room. It cost more than $1,500 to bring Atlantis to Memphis, but he told Reyes, ”You’ll make your money back.” He almost did.

Enrique Reyes is hard at work on a colorful lucha libre mask at his business, Reyes Customs.

Reyes held his first lucha libre event — a match between Atlantis and Tattoo — in November 2013 at Porter Junior High School. Atlantis was the victor at the event, which drew around 300 people. “I didn’t make money,” Reyes says, “but I didn’t lose money.”

His next match, held in May 2015, featured “little people” wrestlers from Mexico, as well as wrestlers from around the country, including Memphis wrestlers Precious and American Gladiator.

Reyes, who spent around $4,000 for his professional wrestling ring, now presents his Memphis Lucha Libre Wrestling (MLLW) events once or twice a year at 3766 Ridgeway Road next to El Mercadito, a Mexican grocery store.

“A lot of people show up to my shows because this is a family show. The kids, they love it. The adults, they already know who it is because they watched it when they were kids.”

He also brings in women lucha libre wrestlers, including Lady Shani, who gave Reyes one of her complete outfits.

Memphis American-style wrestler Dustin Starr has participated in most of Reyes’ events. Starr and his wife, Maria, co-host Championship Wrestling Presented by Pro Shingle at noon on Saturdays on CW30.

Starr enjoys the Mexican style. “It’s different. Faster paced,” he says. “You see a lot of unique offensive and defensive maneuvers. It’s very colorful, especially the masks and the outfits. Those are always over-the-top and elaborate.”

Starr wrestles luchadores when he participates in Reyes’ lucha libre events. The Mexican wrestler usually is the victor, Starr says. “Whatever we do, people boo us like crazy. It’s an interactive crowd. They want to see the luchadores kick our butts. We’ve tagged up a couple of times, but most of the time, I’m the bad guy who wrestles with the good guy luchadores.

“Let me tell you,” he adds, “they can hit you whether you’re in the ring or out of the ring. You never know where they’re going to come from. Literally, nowhere is safe. If you’re in the ring, they’ll dive on top of you. If you’re out of the ring, they’ll dive on top of you. You’re not safe anywhere with those guys. They’re daredevils.”

Reyes began making masks after he asked Atlantis if he could buy his mask during his first MLLW event. “I said, ‘How much do you want for your mask?’ He says, ‘$300.'” The professional masks Atlantis wore sell for hundreds of dollars, but he also wore semi-professional masks. He sold Reyes one of the semi-professional ones for $50. “When I saw the masks, I thought, ‘I can make these,'” says Reyes.

The first mask Reyes made was called the Rey Mysterio Mask, in honor of the wrestler of the same name. Reyes even got Mysterio to sign it for him. Reyes then began getting requests for masks from other wrestlers.

He told Hijo de Fishman, son of the legendary luchador Fishman, who died in 2017, that he’d make a mask for him. “He says, ‘How much will you charge me?’ I said, ‘Nothing. I’ll make one, and you can use it.’ He gave me one of his masks to get the pattern, and I did the mask.”

Reyes says the vinyl green-and-yellow mask he made for Hijo de Fishman is his favorite. It includes gold lamé, which he attached to the mask with shoe glue and fancy stitches made with his sewing machine.

Every mask means something, Reyes says. Hijo de Fishman was “supposed to look like a fish,” which is why Reyes used green and yellow.

A mask featuring a dragon on top was a copy of one worn by El Ultimo Dragon. A pink and purple-ish mask covered with numerals is a copy of one that belongs to a wrestler named El Matematico.

Reyes has made about 30 masks, which he either keeps or sells to mask collectors for about $150. Many of the masks in his collection are ones he bought from luchadores, including Huracan Ramirez and Aguila Solitaria.

Reyes says he doesn’t want to open a mask business because it’s not cost-efficient. “I take maybe 10 hours to make one. You’re talking about another $30, $40 on material. That’s a lot of time and money. That’s why the wrestlers go to Mexico. Because in Mexico they pay like $40, $50 for the full mask.”

Reyes makes masks when he needs a break during his work day. “When I’m stressed, got a lot of things on my mind, I say, ‘Let me do one of these masks.’ Basically, that’s what I do for a hobby.”

He has also made complete outfits for wrestlers, including Starr, who says he “felt like a kid in a candy shop” the first time he saw the masks lining the walls in Reyes’ office.

“The quality of work, all the colors, the designs he makes, they all look really, really good,” Starr says. “So, he exclusively makes my gear now. He’ll do my kick pads, knee pads, jackets, shorts. He puts the designs on, the whole nine yards. And they look great.”

Asked what his mask would look like if he was a Mexican wrestler, Reyes says, “Maybe some Aztec warrior or something like that.”

Reyes’ passion for lucha libre has rubbed off on his 17-year-old son, Luis, who wants to be a wrestler. “He practices because we have a ring at my house,” says Reyes. There’s probably a nice mask or two in his future.

La Lucha Libre: How Mexican Wrestling Came to Memphis