When it comes to breakfast meetings, it’s safe to say the one I had on August 29, 2018, is the most memorable. I joined Harold Byrd, Herb Hilliard, and Dr. David Rudd at the Holiday Inn on the University of Memphis campus. The names alone will tell you this was no friendly “catch-up” over scrambled eggs and biscuits. Byrd is the president of Bank of Bartlett and a significant, active booster of U of M athletics. Hilliard is another local titan in the banking industry, and just happens to have been the first African-American to play basketball at the University of Memphis. Dr. Rudd, of course, is the president of the U of M.

I’d written recently (but not for the first time) about the need for a Larry Finch statue somewhere in Memphis. It was high time this regional legend receive a proper memorial, and particularly during a time divisive statues were being taken down all across the country. If nothing else, Larry Finch was a unifier, both on the basketball court (where he led the Memphis State Tigers to the 1973 national championship game) and off the court (where he somehow made Memphians forget skin color or background in defining themselves as a community).

Dr. Rudd had a few questions for me. He felt like the right kind of statue — along with a memorial plaza, where people could linger — would cost more than my column suggested. But he emphasized his skills at fund-raising and explained, on the scale of a major university in a metropolitan area like Memphis, the cost of the Larry Finch memorial would be no tall hurdle. Finch would get the bronze treatment.

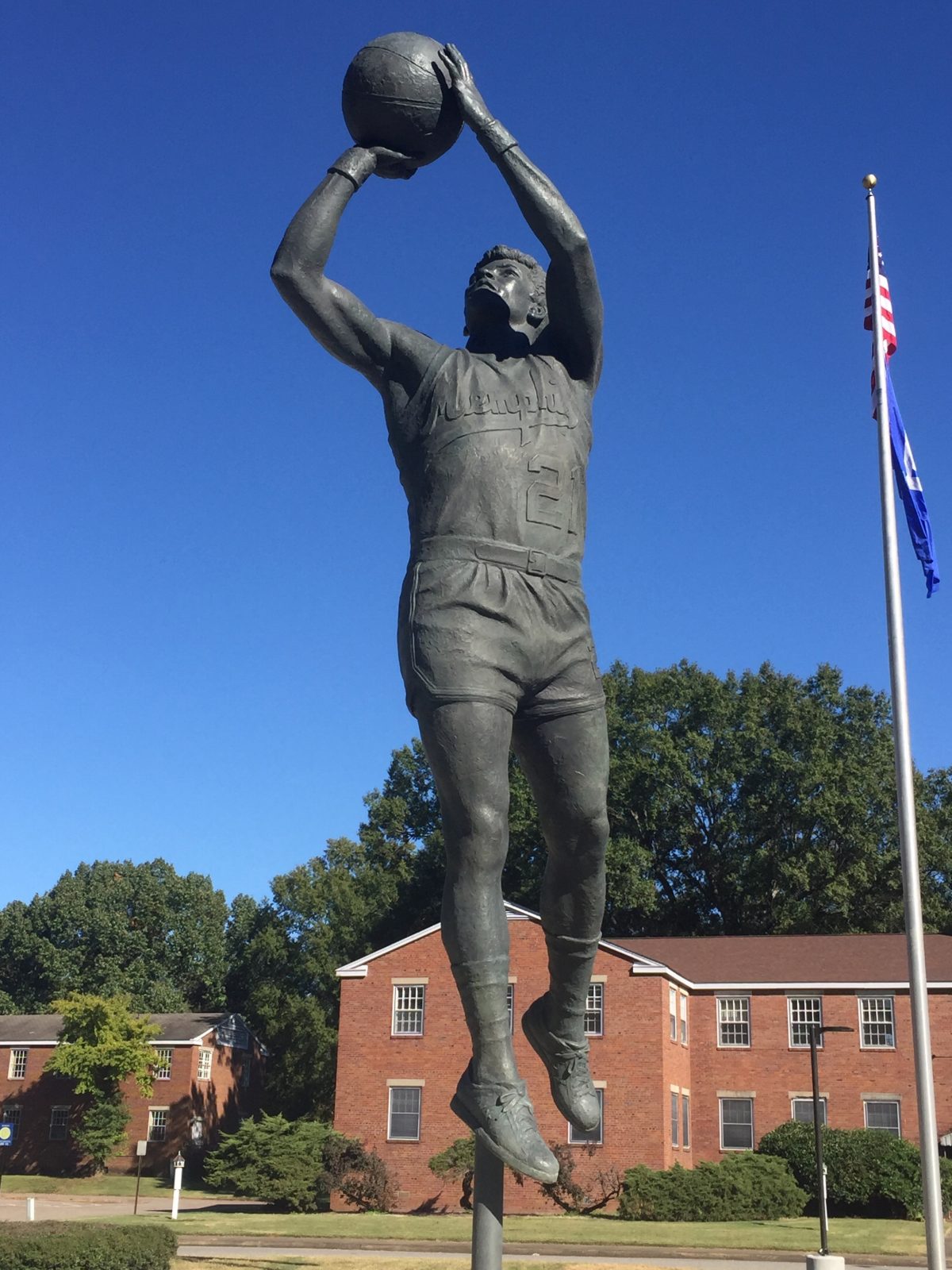

It took more than three years (two of them under pandemic conditions), but the Larry Finch statue now stands proudly in front of the palatial Laurie-Walton Family Basketball Center on the U of M’s south campus. It was unveiled Thursday in front of a few hundred Finch family, friends, and fans (the largest contingent representing his beloved Melrose High School).

Penny Hardaway got choked up at the microphone and needed a solid 60 seconds before sharing his feelings about his college coach. Elliot Perry described spending a few of Finch’s final hours with him. (“I mostly thanked him for being him,” said Perry, the most prominent member of Finch’s first recruiting class as Tiger coach.) Finch’s widow, Vicki, shared a sonnet by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, one she feels reflects the love Larry Finch had for the game of basketball.

Memphis is a happier place today. A better place? That’s up to you and me, the actions we take and decisions we make every day. But Memphis is a happier place today. Larry Finch brought so much joy to so many people in the Mid-South, and across generations. (My paternal grandmother adored Larry Finch and shared the first stories I heard of him and his impact.) It’s criminal that Finch died so young (age 60, in 2011 after a series of strokes). He would have relished Thursday’s celebration, primarily for bringing together — yet again — Memphians who shared something . . . in this case a love for Larry Finch.

We can’t pose for a selfie with “Coach Finch.” (I always refer to him with the title he held for 11 years — from 1986 to 1997 — at the U of M.) But for generations to come, Memphians and their lucky guests can take a selfie with the Larry Finch statue, and read about his legend, his impact, his significance over the precious 60 years we had him.

I’ve come to believe that we can channel the souls of our heroes when near a statue that embodies the right message. Memphis has such a monument now, and there will be some soul channeling, you can be sure, in the years ahead. Larry Finch once again stands proudly. Here’s to all he represents, then, now, and tomorrow.