“Art viewing and art making are incredibly important for my mental health,” says Leslie Holt, whose show “Don’t Let the Sun” closes this weekend at David Lusk Gallery. “It sort of reminds me why I live sometimes. Art’s a life force for me.”

Holt, who is based in the Northeast, says that she’s been into art ever since she was a kid, despite coming from “a family of scientists.”

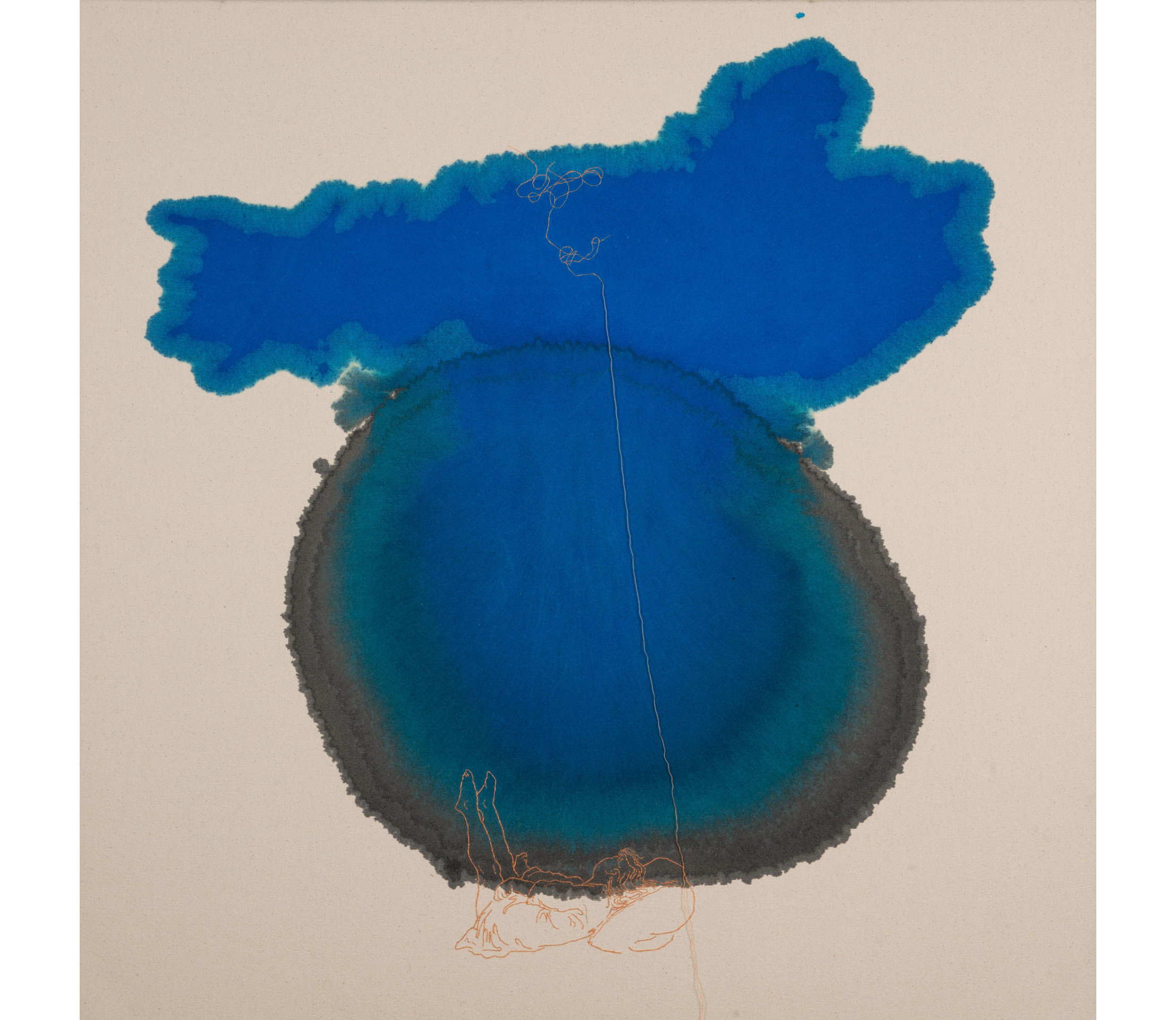

“My sister is a neuroscientist,” she says. “My mom was a physicist.” But even in the pursuit of painting, this hereditary thirst for scientific inquiry didn’t skip over Holt — that much is evident in her “Brain Stains,” which takes inspiration from PET scans of brains from those with different mental health illnesses.

Though they cannot diagnose mental illnesses, as clinical imaging tools, PET scans reveal, through a mapping of an array of colors and patterns, underlying different physiological activities. A PET scan of a depressed brain, for instance, lights up almost entirely in different shades of blue, while a non-depressed brain will light up in hues of red, yellow, and green, with blue present in a much smaller area.

“I’m a very visual person, and I just think they’re beautiful — the scans themselves,” she says, adding that with her family of scientists, “I’m kind of aware of this imagery, not that I have in-depth knowledge of meaning or interpretation behind them.”

Though she has researched extensively for her art, has worked in social work, and volunteers for National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), Holt stops herself from getting caught up in the specifics of the scans and the facts. “There’s a couple in the show that are more literal interpretations, where I’ve translated the color pretty faithfully and the shapes pretty faithfully,” she says, but as the series progressed, “they really became much more abstract.

“I think the PET scan sort of design and diagram started to feel a little limiting to me,” she continues, “and a little bit like privileging the scientific part of what I’m trying to do, how I’m trying to speak about mental health.” To Holt, having suffered depression herself and having witnessed bipolar disorder’s effect on her mother, how mental health operates on a human, personal level takes priority above a clinical definition. Each case varies by person, and each person’s case can vary by moment and situation.

As such, Holt also turned to embroidering onto the canvas phrases and verses of poetry, selected “to speak about the human condition and sometimes the mental health condition in ways that scientific language doesn’t really get to.” Sometimes she will also embroider text from clinical notes and texts like the DSM, suggesting the tension between the interiorization of the clinical and personal language that often coexist after a diagnosis — inseparable yet opposing forces of logic.

But, on the surface of the paintings, a viewer will not recognize all these words because Holt has embroidered them onto the back of the canvas, leaving the front indecipherable, with threads left hanging and tangled, as if undone and lost in translation — “like how communication gets garbled for anybody trying to explain something, but particularly for folks who are in the midst of mental health symptoms.” Five of the paintings, however, are suspended in the gallery space, allowing the viewer to witness both sides of the canvas, a vulnerability offered by few artists.

Also, on view are paintings in Holt’s “Unspeakable” series. The initial inspiration for this series was Picasso’s Guernica, one of the artists’ favorite pieces of art of all time. “I think it captures raw emotions in ways that words can’t,” she says. From there, she branched out to other artists “like Käthe Kollwitz, Frida Kahlo” and their depictions of intense emotion before turning to “hysterical women who were documented by clinicians in the 19th century.”

“The clinicians would draw them and photograph them and make sculptures of them in the midst of a ‘hysterical fits’ to try and understand, to try and categorize the different stages of hysteria,” she says. “And it’s a disturbing history because they would sometimes provoke symptoms or they would clearly put the women on display in front of an auditorium and induce symptoms as a performance themselves.”

The pain, trauma, and exploitation in these moments are unspeakable, marked with shame, obtrusive like the staining on Holt’s canvases that spread behind the suffering figures embroidered onto the surface, mere outlines held together by thread.

When considering the two series in conversation with each other, Holt says, “I think of the PET scans as being sort of modern day interpretations of mental health conditions and then these hysterical women being the historical approach, and questioning which is more accurate and how far have we really gotten.

“What I love is that this work promotes conversations about this topic and is often very affirming, and people will really respond to the fact that I’ve made this topic more public than it usually is. … I think there’s part of me — because I come from a scientific family — that’s like, ‘What right do I have to speak on this topic?’ I am not an expert. And I think [my art is] asserting that it’s okay. It’s sort of empowering.”

“Don’t Let the Sun Go Down” is on view at David Lusk Gallery through Saturday, May 28th. For more information on the artist, visit leslieholt.net or neuroblooms.com, where you can purchase pins inspired by her “Brain Stains.” Ten percent of the proceeds of Neuro Blooms goes to mental health organizations like NAMI.