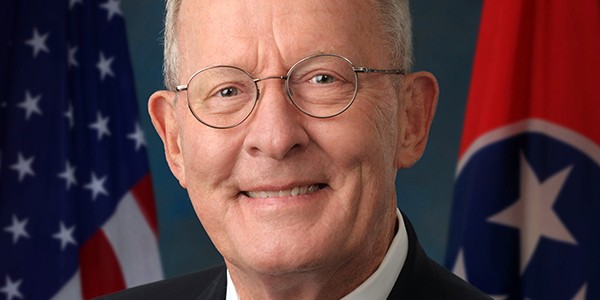

Last week, Tennessee’s retiring senior U.S. senator, Lamar Alexander, delivered on a long-standing promise to make himself available to the Flyer for our version of an exit interview.

A very brief, edited version of that interview was published in this week’s hard-copy version of the Flyer. That version merely excerpted Alexander’s answers to our request that he describe Donald Trump and Joe Biden and that he comment on a recent installment of the Rachel Maddow Show on MSNBC recalling his early accession to the Tennessee governorship in 1978 to forestall the inevitability of predecessor Ray Blanton making illegal pardons (this in light of rumored pardons to come involving outgoing President Trump).

Here, minus a bit of small talk on both ends of the conversation, is the interview in its entirety, edited here and there only for clarity.

Now that you’re exiting the Senate, what are your plans?

I’ve deliberately not made a plan. I heard a sportscaster say about a basketball player, that could be a much better basketball player if he stopped trying too hard, and let the game come to him. And so that’s what I plan to do. I’m going to move back to our home in East Tennessee with Honey, and see what comes. The life I’ve lived has been a fascinating life. For the last 50 years, I’ve had one of the best seats in the house. And I’m gonna turn the page and see what chapter breaks.

I know the one thing that in all the interviews you’ve had, and and for that matter in conversations you have with people, the one question that in one form or another always comes up is what I’m going to ask you now: Can you give a brief capsule of Donald Trump as you understand him to be?

The one thing that we can see certainly is, he is an effective communicator. Ronald Reagan was called a great communicator for his day, but in a completely different way. President Trump has mastered the internet democracy in a way no other public figure has.

Nobody else comes close to exciting 72 million people on Twitter to pay attention to what he says several times a day. So he’s certainly a great communicator. He’s self confident. He’s gregarious when you’re around him. He’s ambitious.

I’ve seen him in private where he works very well on issues like the great American Outdoors Act, which would not have happened with without some key decisions that he made or efforts to lower insurance rates for people who don’t have Obamacare subsidies. He’s like a lot of people who’ve been in business and not in politics. He’s thin-skinned and he’s not accustomed to criticism.

And he has a style and behavior that’s different than any of the presidents we’ve recently had, which sometimes obscure his considerable accomplishments, like lower taxes, conservative judges, fewer regulations, and probably the most remarkable of all, presiding over a government that produced a 95 percent effective COVID vaccine, and eight or nine months, instead of eight or nine years.”

Editor’s note: The COVID vaccines currently being touted as effective were not created by the United States government, or even in the United States.

Can you provide a similar capsule for President-elect Joe Biden?

Joe is gregarious, decent, friendly. He’s well known and well liked in the United States Senate. He has the advantage of knowing leaders all over the world. He was chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee for a long time, and he has been vice president. So he should come to the presidency about as well prepared as anybody could. His biggest challenge is going to be the left wing of his own party. Because when they head off into socialism and defunding police, they lose more than half the country. And if he resists that, he’ll be able to gain some significant Republican support, I think, and be an effective president.”

I’ve worked with him easily. I told a story in my farewell address about that, how we were working on the 21st Century Cures legislation which has done so much among other things to speed the treatments in the vaccines that we see today. And I got stuck, and I called him and said, Joe — he was Vice President — I can’t get the White House to move. I’ve got President Obama, personalized medicine, and the bill. I’ve got the Cancer Moonshot in there for you. Mitch McConnell wanted regenerative medicine, that’s in there. Paul Ryan has figured out how to pay for it. But I can’t get the White House to move — like the butler, standing outside the door of the Oval Office, where the order on a silver platter and no one will open the door and take the order. And Joe Biden said, if you want to feel like a butler, try being vice president. So I worked with him well.

On 21st Century Cures, he [Biden] played a big role in getting that done. And I’ve watched him work with Senator McConnell before on behalf of the Obama administration to come to some agreements about taxes.

It was interesting that, on the day after your farewell address to the Senate, you made a speech in tribute to Congressional staff members.

What I realized the was that, you know, the staff is absolutely crucial to the success of any senator. I couldn’t possibly have shown proper courtesy or efficiency or understood the issues without some really talented, hard working staff. And I realized that if I tried to thank them during my farewell address, it would make the address too long to properly acknowledge that. Maybe the salute to the staff speech yesterday, will start a new tradition in the Senate. In addition to the main address when you arrive and the farewell address, when you leave, I think a salute to the staff speech would be a nice tradition in the Senate.

I asked you to characterize Trump and Biden. What about Kamala Harris? You had a chance to have a chance to get to know her.

She’s only been there for two years and she’s been running for president for most of the time, so I don’t know her very well.

Okay, well, one more of those. Bernie Sanders was asked years ago what Republicans he respected and he named your name. That was the only name he mentioned, in fact. he said, “I like Lamar.” So let me ask you, what are your thoughts about Bernie?

Well, I like Bernie. I just don’t agree with him. We’ve served on the same Labor Committee. We have to work together, which I do with all senators. And one thing we both agree on is the importance of community health centers. So even when you have as many differences as I do with Bernie Sanders, it’s possible to list find some things that you both agree on.

One of the things that you spoke of in your farewell address was filibusters. And as I understand it, the way filibuster rule still applies is that 60 votes are required for cloture of debate, except in the case of executive nominations and judicial nominees? Is that correct?

That’s right. We used to have a requirement of 60 for a presidential nominee, but nobody ever did. I mean, not even Justice [Clarence] Thomas had to have 60 when he was nominated. He was 52 to 48. None of the senators who opposed him asked that there be a 60-vote requirement. But on legislation — not nominations, but legislation — what the rules require is that before you vote on it, you have to cut off debate and you’ve got to have 60 votes. You can’t just pick the Republican majority on something like The Every Child Succeeds Act and slap through a Republican fix. I’ve got to go sit down with Patty Murray, who’s the ranking Democrat on the committee and say, ‘Patty, I need to get to 60 votes on this.’ So can we come to a broad bipartisan agreement on it? We did that. And in fact, 85 senators voted for it. And if we can come up with something that 85 of us can vote for and live with, then the country can live with it.

That’s the same with civil rights, Medicare, Medicaid, the Panama Canal treaty. The real purpose of the Senate is to use to tackle tough problems and see if we can get a broad agreement. And the filibuster forces us to do that. But not all, just to run a freight train through the house and let the majority just steamroll the minority.

A subject was highlighted recently on The Rachel Maddow Show that I’m sure you’ve heard a lot about. This was the Blanton pardons causing your early accession to the office of governor. Do you see an analogy between the Blanton pardons, as scandalous as they were, and the prospect of President Trump pardoning a whole slew of people, including his relatives, and maybe himself?

No, I don’t. I don’t. What was happening in the Blanton years was evidence that people were paying cash for pardons in case for clemency. That was the problem. And the United States Attorney knew it. And he was a Democrat. He called me and asked me to be sworn in early to stop that. I haven’t heard any kind of allegation that anyone’s paying in order for a pardon or clemency. And it’s certainly not unusual for a president or a governor to issue pardons or clemencies at the end of a term. President Clinton, President Bush? Well, I won’t say … I know President Clinton made pardons. Most presidents, most governors issue them during their time, and especially at the end of their time. The issue in Tennessee in 1978 was cash for clemency, not just clemency.

There has been speculation that there may be some cash involved.

Oh, there’s speculation all over the thing. What they had in Tennessee in 1978, the FBI had proof of it, and the U.S. Attorney knew it. And Blanton had said that he was going to pardon or grant clemencies to people that the FBI and the U.S. Attorney knew had paid cash for their release.

You were born and raised in East Tennessee, and even in in times of the domination of Tennessee by Democrats, East Tennessee was Republican. How much of your Republicanism do you think derives from the circumstances of your birth and how much is by choice?

Oh, a lot of it derives from the circumstances of my birth. My great grandfather, John Alexander, was a union officer in the Civil War, from Blount County, and he was asked his politics, and he said, “Republican. I got shot.” So when I started in politics, the Republicans in Tennessee were the Lincolnites, and the Lincolnites were the mountaineers who came from families have fought with the Union in the Civil War. And the black Republicans, which were the Lincoln league and Memphis, that was the Republican Party in the ‘50s, and ‘60s in Tennessee. And that gradually changed over the years. And the Democrats at that early time were people with Confederate ancestry. So the Civil War dominated the voting patterns in Tennessee until very recently.

Something that’s kind of fascinating to me is that [Senator] Marsha Blackburn, who is certainly a very ideological Republican, hails from a Union county in Mississippi. That is probably how that twig got bent. You knew that, right?

Well, I did, I had heard that and and, and that that’s the same as my one county where I’m from. The congressional district in which I grew up, and where I’m going to live after I retire from the Senate, has never elected a democrat to Congress since Lincoln was President.

Okay. As I told you, I’d be skipping around a bit. One thing you kept saying when you were running for president in 1996 was that, at every stop you mentioned how you lamented the passing of a time when school boys could take a pocket knife to school. I understood that to be an implicit metaphor, but I didn’t quite grasp it. What did that mean to you, the pocket knife reference?

Well, what that meant to me is that standards and behavior have changed. When I was a kid, most boys carried a pocket knife to school, but we never thought about using it on each other. And if we had, we would have ended up in in very, very serious trouble. Nowadays, behavior is such that they don’t allow pocket knives in schools. And I think that’s a commentary on our family structure, on the pervasiveness of television, and the pervasiveness of social media, and a lowering of behavioral standards around the country. You’re right, it was a metaphor. But I think it was an important one. And what I was trying to say was, that wasn’t a problem that Washington could fix and that if you want to save school, that you had to fix it in your own community.

Also, in 1996, when you were running for president, why did you want to abolish the Education Department which you had headed?

Well, I thought we didn’t need it. If you if you remember in 1980 or ’81, when I was governor, I asked for a meeting with President Reagan. And I proposed that to him: Why don’t you get the federal government completely out of elementary and secondary education? And in exchange, why don’t you take over Medicaid and get the states completely out of Medicaid, so we have accountability, so everybody will know the responsibility for making a good school lies with state and local government, and the responsibility for Medicaid lies with the federal government.

I didn’t think we needed an entire department to spend the federal dollars to help education. Except for about 8 or 9 percent, all the money that’s spent for schools really is for low-income and disabled children. We could just have a check-writing operation that would send that out to parents or to school districts, to the schools where those children were. That was only a few years after the department was created. And what I said in the 1990s was the same thing I said, the 1980s.

And, and then more recently, when we fixed No Child Left Behind, in 2015, the whole purpose of it was to get Washington out of elementary and secondary education, and reduce its role. And the Wall Street Journal said, that was the biggest evolution of power from Washington to the states and 25 years. It just comes from a conviction I have that if you want good schools, you’re going to have to create them yourself. And you can’t expect people at a distance to improve student achievement in the third grade very much. It’s gonna have to be the teacher and the parents in the community. Who makes that happen?

Well, you’ve answered what would have been my next question. I was going to ask the main difference between every the Every Child Succeeds Act, which you sponsored, and No Child Left Behind, which it replaced, but you sort of accounted for that.

That was the whole point of that — to restore to classroom teachers and local school boards and parents a lot of decisions that have been transferred to Washington and to what had, in effect, become a national school board, saying, ‘This is what you should teach. This is how you should define what a good teacher is. This is what you should do about a school that’s in trouble. This is, this is how you should reward outstanding teaching.’ And my thought is that that can’t be that can’t be done from a distance it needs to be done locally.

I am interested in your reference to what you say you said to President Reagan about Medicaid. What are your thought as of now? You opposed the Affordable Care Act? What are your thoughts about it as of now going forward? And what do you think about the Medicare- for-All proposal?

I don’t like Medicare-for-All, because what it does is take away your private insurance. And most people who have insurance on health insurance on the job like that insurance, and when they hear that Medicare for all means that if you’ve got insurance at FedEx, or if you got insurance in your small business, or wherever, that that’s being taken away, and you’re being put into Medicare, they don’t like that idea. So I don’t favor Medicare-for-All.

What I tried to do was to push more of the decisions about insurance policies back to the states, where they had been before so there could be a greater mix of policies offered, and people could be able to afford health insurance. I think the one thing that won’t change is that of pre-existing conditions whereby we’re past the point of having a country in which pre existing conditions aren’t covered by insurance. So everybody who wants it should be able to buy a policy that covers pre existing conditions.

In your farewell address, you were also pretty eloquent about the virtues of the two party system. Is there a case to be made for a strong third party in this country?

I don’t think so. Because I think the whole point of government is to deal with big problems, whether it’s fixing schools or roads or health care or civil rights or racial justice, and come up with an agreement or a conclusion that most of us can live with. And if we get too splintered — we have three or four or five parties — it makes it harder to come up with a consensus. So I think we have it about right. In the United States Senate, you have two parties. And then you have a requirement that you’ve got to work with the other party to get to pass a major bill. And so if we ever succeed, then we’ve got an agreement that most of us can vote for and that most of the country can live with. And that agreement usually lasts for a long time. And I think a three-party system would jeopardize that.

I’ll boil things down to two last questions. And one of them is: What was or has been the main mistake of your political life, the one thing you wish you hadn’t done? Or could correct?

The main mistake …[pauses]

You may have made one or two; most of us have.

I should have walked across the state in 1974 instead of 1978. That’s one. That’s one big mistake. I would have learned a lot more about the state and I would have been a lot better candidate and might have been elected that first time, and I would have been a lot better governor.

That’s an interesting answer. Now, what would you say is the main achievement of your political life?

Well, in general, I think I should let others figure that out. I mean, I’ve tried to leave footprints that are good for the state and good for the country. Now that I’ve had a chance to look back 40 or 45 years, the bringing the auto industry to Tennessee in the early 1980s probably has done the most to raise family incomes and improve our standard of living. In Tennessee in the early ’80s, we had no auto jobs. And suddenly, over a period of time, we became in some ways the number-one auto state, with with the Saturn, Nissan, and Volkswagen plants, and nearly 1000 suppliers in virtually every county. And that came at a time when Tennessee was the third-poorest state,when many of our textile jobs were leaving. And these new jobs that arrived were better jobs, higher paying jobs, and better jobs for the future.

So helping to bring the auto industry in, which in turn, caused the three big road programs that I proposed, so we’d have the best four-lane highway system in the country, with zero debt. We paid for all that with taxes in order to bring the suppliers, so suppliers can make just-in-time delivery. Even the better Schools Program was a part of that, because I realized after a while that if we want to get better jobs, we needed better schools. But the short answer would probably be bringing in the auto industry.

Well, it looks like I’ve got maybe room for one more question: Did you have to take positions as a member of the Republican leadership that ran at all counter to your personal preferences?

Oh, I’m sure. I’m sure there were positions that I took for the entire Republican caucus that wouldn’t have been the first thing out of my mouth if I’d only been speaking for myself. You know, I was selected chairman of the conference three times. And after a while, while I enjoyed it, and I thought I was good at it. I got tired of i, because it was all politics. It was political messaging. And I thought there’s a better reason to be in the United States Senate than that.

It’s hard to get here. Hard to stay here. And while you’re here, you might as well try to accomplish something good for the country, and I was becoming chairman of a couple of important committees. So I left that political messaging job to work on the issues I care the most about, And the last nine years have been very satisfying. For me. I feel like I’ve gotten up almost every morning thinking I could do something good for the country, and gone to bed most nights thinking that I had.