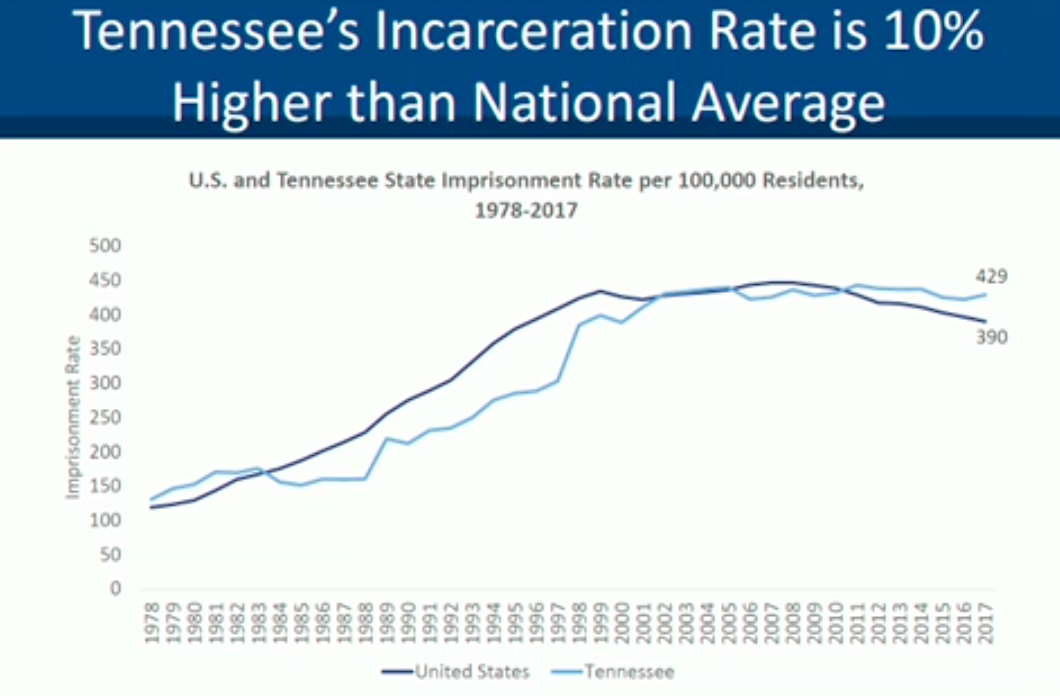

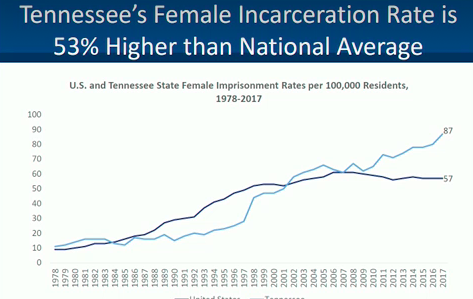

Tennessee’s incarnation rate is 10 percent higher than the national average, its female prison population rate has exploded, spending on corrections has surpassed $1 billion, and the state has the fourth-highest violent-crime rate in the country.

That’s all according to researchers with the Crime and Justice Institute (CJI), who presented their findings Wednesday to members of the Tennessee House Judiciary Committee. Those researchers were tapped to join a task force last year and charged by Gov. Bill Lee to review the state’s criminal justice system.

The task force released its findings in an interim report in December. That report recommended lawmakers review criminal sentencing, reduce sentencing times for some parole violations, and more.

State Capitol building

CJI staffers Maura McNamara and Alison Silveira presented some of the information to lawmakers during what could be a two-year overhaul of some of the state’s criminal justice policies meant to reduce the prison population.

The presentation and hearing was one of the first times legislators were able to dig into the data and ask questions about the study.

The researchers said the state incarcerates around 13,000 people each year. Admissions to prison have declined overall by 14 percent, they said, since 2009. However, while admissions have fallen in West and Middle Tennessee, admissions rose in East Tennessee by 500 from 2018 to 2019. (West Tennessee admissions fell from about 4,500 in 2009 to about 2,900 in 2018.)

Crime and Justice Institute

Crime and Justice Institute

The bulk of incarcerations (74 percent) last year were from what researchers called “non-person” offenses like drug and property crime, and vehicular offenses. The rest (26 percent) were violent crimes and sex offenses.

In all categories, the average length of time served by felons in Tennessee rose by 11 months over the last 10 years, from 48 months to 59 months, Silveira said.

“People released in 2019 are serving nearly a year longer behind bars than those in 2009,” she said.

The large amount of non-violent incarcerations drew the ire of Rep. Antonio Parkinson (D-Memphis), who called the figure “an indictment to us who sit on this committee.” He also noted that “I think our policies are causing some of these — if not all of these numbers — to be in the place that they are.”

However, Rep. Andrew Farmer (R-Sevierville) reminded the committee members that “all of these crimes are crimes against society.”

“We make laws up here not because we want to see people in jail, we don’t,” Farmer said. “We don’t make laws up here because we want to waste taxpayer dollars. We don’t make laws up here just to keep people in jail.

“We make laws up here to see those who violate out laws here in the state of Tennessee are pushed appropriately. We want them to become rehabilitated and we are doing the very best we can to do that.”

Lee said last year the task force’s main aim to reduce recidivism, the act of people being re-arrested after they’ve been released from prison. McNamara said nearly half (47 percent) of those released from custody here over the last 10 years, were rearrested within three years.

However, 40 percent of those are rearrested because they broke their parole on technical violations, not on new crimes, Silveira said. They’ll go backup prison because they moved and didn’t tell their parole officer, failed to pay a monthly fee, or failed to appear at a meeting or hearing.

Google Maps

Google Maps

Riverbend Maximum Security Prison in Nashville is home to Tennessee’s death row.

“The reason a person usually goes back to jail has more to do with the challenges of returning home than a sign of criminal conduct,” Silveira said.

Rep. Joe Townsend (D-Memphis) wanted financial data, noting “the state is spending extraordinarily large sums of money to re-incarcerate people for technical violations.” He said if the state locks up about 13,000 people each year, and their length of stay has risen by about a year, “that’s like an additional 13,000 years.”

The state’s female prison population grew 41 percent over the last 10 years, from 2,364 in 2009 to 3,481 in 2019, the researchers said. Female felony offenses mainly involved drugs and property, they said, though didn’t offer detailed insight as to why the female prison population was surging.

Rep. G.A. Hardaway (D-Memphis) wants to learn more. “I am so disgusted that we are evidently not doing what we need to do to keep our women from choosing a life of crime and from being incarcerated,” Hardaway said. “I don’t know what the answer is. But I sure would like to find out and do something about it very quickly.”  Crime and Justice Institute

Crime and Justice Institute