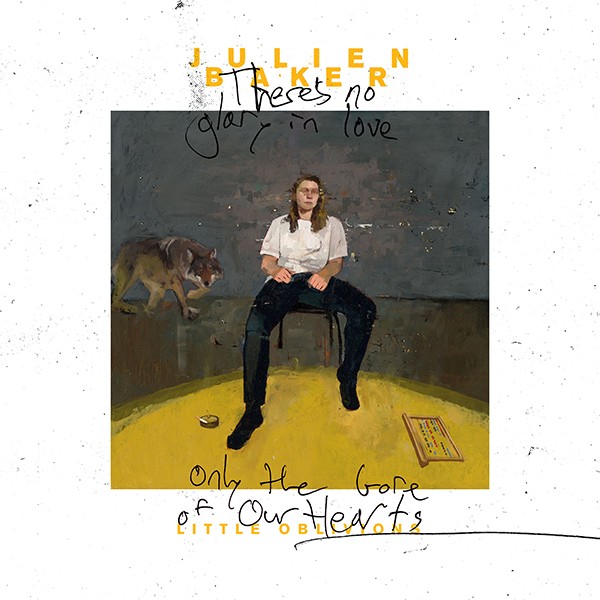

When I pull up Julien Baker’s new album, Little Oblivions, and hit play for the first time, I am jolted out of my expectations by the crass tones of a cheap, possibly broken organ or Mellotron blasting blocks of chords like a fanfare. It’s an ennervating shot across the bow from an artist more typically associated with delicate guitar lines that hypnotically draw listeners in to the hushed-to-frantic intimacy of her voice. As the song develops, those chord blasts are joined by mellower synth-strings, and you can hear echoes of her past work more clearly, even as she begins to sing words from darker, grittier depths than she’s ever plumbed before.

Blacked out on a weekday; is there something that I’m trying to avoid?

Start asking for forgiveness in advance for all the future things I will destroy.

Alysse Gafkjen

Alysse Gafkjen

Listeners won over by Baker’s bare bones debut, 2015’s Sprained Ankle, or her first album on Matador, 2017’s slightly less minimalist Turn Out the Lights, may expect more of her trademark romanticism-cut-with-blunt-realism approach, and that’s in evidence here, but it’s soon apparent that she’s taking the bluntness several steps further, mixing intimations of anguish with wry observations on the prosaic fumblings of everyday life. As she sings on the second track, “Heatwave”:

It’s worse than death, that life, compressed to fill

A page in the Sunday paper; and I had the shuddering thought:

“This was gonna make me late for work”

Everyday tragedies that make you late for work: such are the impressions of an artist who’s confronting reality, from the mundane to the spiritual, on whole new levels. And, as the world saw when she appeared on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert last month, this time she’s got backup: a full-on rock band. And yet, despite such world-conquering moves, this quarantined life humbles us all, and when I call her, the first thing on her mind is getting back to Memphis, where she first learned to play with a band before a fluke recording opportunity made her a solo star.

Memphis Flyer: You’re a Memphis native, and recorded both of your records for Matador here, but now you’re living in Nashville. Are you settling down there?

Julien Baker: I’ve always had this nomadic span between Memphis and Nashville, and this is the longest I’ve been away from Memphis. And it makes me really sad. My parents and a lot of my friends have moved to other cities. So when I do come back there, it feels underpopulated. I still consider that my home-home. Memphis, with all the music that comes out of there, has an outsider-ness to it, but I worry about gentrification. I fear Memphis becoming a cariacature of itself in the way that other cities have. Maybe it’s because I live here in Nashville and I see it so much. There’s actually a rich and inclusive community in Nashville, but it is underneath layers and layers of irony and branding. I don’t want Memphis to feel like it has to acquiesce to the stylization that I see in a lot of other cities, in order to legitimize itself.

That old backwater feeling of Memphis can help more idiosyncratic artists thrive. Did you feel like that growing up here?

Completely. When I was growing up, I felt like in my little microcosm of the music scene it was booming. Because I would go to the skate park all the time and see seven-band bills that were weird metalcore, hardcore, or deathcore bands, and it would be packed. And that felt like such a massive era to me, because I was a kid. I was part of a close-knit house show community, and we’d play little art galleries, or parking lots. And then there was this big gulf between that and Minglewood Hall or the Orpheum. I’d go to the Orpheum to see Death Cab for Cutie knowing that they’re on a B city tour. We’re the city they didn’t bother to hit on the first tour. [laughs] Something about that, when you’re making music in that sort of a petri dish, there’s less posturing because there’s less expectations. The people you’re relying on to come to your shows and support your music have less power in the commercial music world. And that’s what gives you the freedom to not feel so performative. When bands play New York, it’s a big deal. When bands play Nashville, industry people are there and it’s a big deal. When you’re in Memphis, you’re collecting all the scraps of culture as it trickles down to you. And then assembling them into this clandestine collage. When you have limited resources, the resourcefulness makes you experimental and inventive.

You can see that in your debut. It was hard to pin down, stylistically.

It’s funny because even that record is made out of a lack of resources, trying to assemble something out of just a looping pedal. The whole reason Sprained Ankle got made was because I had this friend in college [Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro] who had free studio time. I wanted the Memphis band I was playing with, Forrister, to come up and record some songs. And they couldn’t get off work. So I was like, “Okay, I don’t want to waste this studio time,” and I made that record. And then a label wanted that record, and all of this stuff happened to me. But those songs are just things I cobbled together alone in college because I didn’t have my boys with me. To me it sounds like a scratch track where all the instruments are missing.

Anthony Cabaero

Anthony Cabaero

From the “Faith Healer” music video

So when I told my band, “Hey, a label wants to sign me, and they want me to make another solo record and they want me to tour,” they were all excited for me but undeniably disappointed. And I was too, because I had imagined that we’d all do this together, and that my band and I would be musicians for life, as a career. And that’s not what happened.

Now, starting with The Late Show, I’m playing with a full band again. Calvin Lauber, who recorded my music, both Turn Out the Lights at Ardent and this new one at Young Avenue Sound, is playing bass, and Matt Gilliam from Forrister, who I’ve been playing with since I was 14, is playing drums. And it was so much more fulfilling to me than just seeing my lonely body standing onstage. Because it felt like I was standing on the invisible shoulders of all these people who played with me, and then I reaped all the credit. [laughs] It always felt very bizarre, and I struggled with that.

So it was coming full circle, being back with your bandmates?

Yeah. It’s not quite the old lineup, but it’s still meaningful to me to have Memphis people who I grew up with playing with me. And one reason Calvin and Matt and I have such good musical chemistry is because we came from the same subcultural milieu of the Memphis scene. And it feels so much easier for me to enjoy the music when it’s a group effort. It’s not just me, a single body onstage demanding attention, being the sole person producing sound. It is an ongoing collaborative auditory conversation that the band is having. I’m ecstatic to be playing with a band. [laughs].

It’s ironic, because I gather that you played most of the parts on Little Oblivions.

Calvin and I made the record together, and I played most of the instruments. I think he played guitar on one track and a little bit of drums. But it was just me and him building this studio creation.

There are a lot of drums on the new record. Are those loops? They’re showing off their sampled-ness. It’s a cool, disarming effect.

Oh yeah, the sound of a really overcompressed drum machine! I was so worried about how to use a drum machine in a tasteful way. Also, I played a lot of the acoustic drums, but I’m not good at drums. I just knew the parts I wanted. So I would do 16 measures of a drum beat and Calvin and I would try to splice together usable takes. I used to hate that or consider it dishonest studio magic. And I don’t know what flipped in my head with this record. I had noises in my head and I wanted to accomplish them.

I also wanted to explore ugly sounds. I love ugly sounds in beautiful songs. But looking back on my records, Turn Out the Lights is this glossy, beautiful, clear-toned combination of instruments, and I felt like what was missing was that aggressive disjuncture between the softness of the songs and some ugliness.

![]()

Julien Baker (left) and Calvin Lauber, with Matthew Gilliam in tracking room

When I was making Turn Out the Lights, I thought using a Mellotron guitar pedal at the end of a song was a big sonic jump. “Playing it safe” is a reductive phrase, but in many ways I was making sounds that were beautiful only then. I wasn’t really pressing myself to try to integrate weird noises. It’s sort of the opposite on this record, and I like that.

The sounds are of a piece with the lyrics on Little Oblivions. You’re a little grittier and harder on yourself in the new songs.

Yeah, there’s a lot of waxing philosophical on Turn Out the Lights. I think I wanted so badly to write songs that were about healing and recovery, and if they were sad, they still offered the possibility to triumph over negative things. I think that was noble of young me [laughs], but also maybe a little bit idealistic. And undoubtedly I’ll look back at this record and think it’s pretty nihilistic, but maybe that’s just the shift of the pendulum that I needed.

The songs on the new album have a kind of groundedness in day-to-day experiences. Like “a weekend on a bender,” that kind of specificity, or “let’s meet when you get off work.” That sort of prosaic, daily life stuff, and then the emotional universe comes crashing through while you’re “cruising down Main Street.”

I don’t think I realized it when I was writing the songs, but they’re more bodily. They are more grounded. A lot of that has to do with me learning how not to live in the world of my head so much. The record’s pretty candid about things like substance abuse or physical violence. And those are things that, in a jarring, scary, destructive way, jolt you back into the experience of your body.

For a long time, I thought of my behavior and my sobriety as this power of the mind to subdue the body. But that’s a very Puritanical way to think of your body, as just a flesh suit for your mind. You know what I mean? It’s just very disassociative to be always transcending something instead of just inhabiting your body. And so I think, for better or for worse, it’s like situating my life back into my body, and being more present in my day-to-day life experience was a big part of that shift on this record.

In the song “Faith Healer,” you evoke both a “snake oil dealer” and the desire to just feel something, anything.

People are drawn to substance abuse or even organized religion because it makes them feel something. And we’re assuming that what it makes them feel is what they’re after. What I was after, what anybody’s after, is the thing that makes you feel good. There’s an inevitable balance of pain that comes with the things that make us feel good, and yet we return to it: in toxic relationships, in substance abuse, in church. I’ve changed the way I think about religion and my various other convictions. Like my political beliefs. There’s a sort of disillusionment that can be good. When I reevaluated all my behaviors and I think, “What am I actually coming to these things for?” If it’s just as compulsive as an addict, for me to wake up at 4:30 in the morning and read my Bible every day, then why don’t I just drink? [laughs]. You know, if these are basically dealing with the same issue?

Religion, belief, belonging to a political identity or a social group or some particular conviction of behavior — I adhered to all those things because I thought they would make me feel safe and assuage my anxiety. And that’s also the very same longing that makes me susceptible to substance abuse. Those things aren’t unrelated.

It seems like you’re trying to bring more intentionality to faith — or drinking. Whatever it may be, do it with more intentionality. You say “I don’t mind losing my conviction, it’s all a relative fiction.” It’s like you’re seeing these scripts or constructs that humans create. But it’s not quite nihilist to me. It seems more existentialist. Like you’re choosing your script to suit your life needs with more intentionality.

Precisely! I think that’s something very real that you’re getting at. Instead of having a schema of faith outside of my being, it’s more like coming to faith as a lens for the world, and choosing how I apply that lens. What tools I take from faith to help me be a better human being. And it’s the same thing with substance abuse. For a long time, I had an oversimplified, self-constructed narrative about sobriety. But I had to re-approach sobriety as a practice rather than as an ideal. And in terms of faith, instead of trying to figure out how to define God, I had to shift faith into a practice. Now, the part of faith that resonates with me is the community aspect. The cultural aspect.

I hear that in your lyrics. “A character of somebody’s invention/A martyr in another passion play … I’ve got no business praying, I’m finished being good/Now I can finally be okay in not the way I thought I should.” The consideration you bring to your words propels the album beyond nihilism.

Yeah, ultimately nihilism becomes just as painful and limiting as idealism. You have to learn how to be a person eventually. And that is what is called “your twenties.”

Little Oblivions drops this Friday, February 26th, on Matador Records. On Thursday, March 25th, Julien Baker and band will perform a streamed concert in support of Little Oblivions from Nashville’s Hutton Hotel, with three screenings aired at 8 p.m. AEDT, 7 p.m. GMT, and 9 p.m. EDT. Tickets start at $15, available exclusively at audiotree.tv/streams.