This May, 60 years after the Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, with its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, a group called the Journey for Justice Alliance sent civil rights complaints to the Justice and Education departments. The group argued that too many failing public schools in black neighborhoods are being closed and replaced with charter schools.

You read that right.

The debate over racial inequality in education has been reduced to complaints that black children are victims of discrimination because they can’t walk to bad schools in their neighborhoods.

“Children are being uprooted, shuffled into schools that are no better than the ones they came from,” Judith Browne Dianis, a leader of one of the Justice Alliance’s organizations told The Washington Post.

The complaints meld perfectly with the views of teachers’ unions. The teachers oppose closing neighborhood schools that operate under union contracts and oppose opening charter schools, which are typically non-unionized.

This attack on charter schools comes a week after the House, in a rare bipartisan vote, approved a bill to put more federal dollars into expanding charter schools. The House Education and the Workforce Committee bill was written by its Republican chairman, John Kline of Minnesota, and supported by its ranking Democrat, George Miller of California.

Kline told reporters that Arne Duncan, the secretary of education, supports the bill and will urge Senate Democrats to pass it. In a Congress that’s politically paralyzed over efforts to update the Bush administration’s plan for improving public school performance — No Child Left Behind — the charter school bill is the first sign of a breakthrough.

In the last decade, cities from New Orleans to Chicago and Newark have closed record numbers of neighborhood schools and invested money in charter schools. The charters can be located anywhere and draw students from across the city.

The flight to charter schools conforms with the Brown ruling’s central premise: that students should be able to attend the best public schools without regard to income or race.

Thurgood Marshall, the lawyer who won the Brown case and later became a Supreme Court justice, told me as I was writing his biography that the case was not really about having black and white children sitting next to each other. Its true purpose was to make sure that predominantly white and segregationist school officials would put maximum resources into giving every child, black or white, a chance to get a good education.

In filing complaints, liberal activists are putting more value on having a bad neighborhood school than getting a child into an excellent school. The charge that some charter schools are no better than the neighborhood schools being closed ignores the truth that some charter schools have produced better results. Also, parents have the choice to pull their kids out of charter schools that don’t help their kids.

It is also proven that getting black and Latino students out of low-income neighborhoods is good. This year, a study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that minority children from schools with a racial mix were more likely than students remaining in racially isolated neighborhood schools to graduate, go to college, and get a degree.

Earlier this year, a study by the Civil Rights Project at UCLA found neighborhood schools enforcing a “double segregation,” in which minority students remain isolated by race and income. That double burden left schools in poor neighborhoods with the disadvantage of educating students with high levels of poverty, more health problems, more street violence, and fewer positive role models.

In 2012 the same group reported “teachers of all races viewed schools with high percentages of students of color and low-income students as less likely to have family and community support,” which are critical to the success of any school.

Duncan recently described the nation’s school dropouts as disproportionately black, Latino, Native American, and poor.

Duncan also noted that in the fall of this year, the majority of American public school students will be non-white. And yet there are now minority parents and civil right groups being used as props by teachers’ unions to oppose school choice by calling efforts to close failing neighborhood schools the “new Jim Crow.”

Ending racial and economic isolation of students is a sign of progress that is in the best tradition of a nation still struggling to offer every child a quality education.

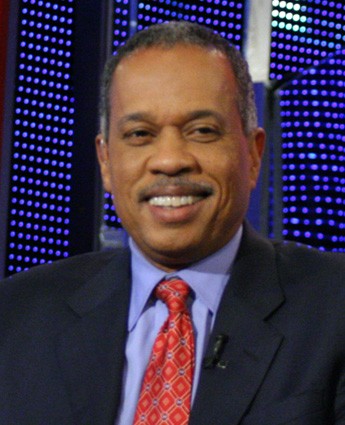

Juan Williams is a Fox News political analyst. Previously, he was the senior national correspondent for National Public Radio.