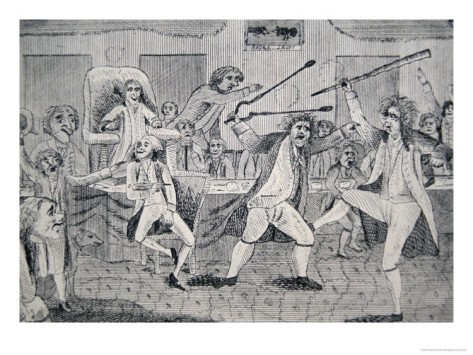

I take some comfort in a crudely drawn political cartoon from 1798 that depicts American congressmen fighting with fists, feet, clubs, and fireplace tongs. It reminds me that incivility isn’t some new creation midwifed by Jerry Springer, refined by talk news, and perfected by the modern House of Representatives. Ignorance, bigotry, and bad behavior have always been with us, although digital and broadcast media have certainly turned up the volume in recent decades.

Just look at all those guys going at it. If they weren’t all white it might be a scene from Clybourne Park. I say that because the Pulitzer Prize winning drama, which is currently available for consumption at Playhouse on the Square, is a loud and noisy play. Voices compete with radios, phones and other voices as characters talk to, at, and over one another like impasse and misunderstanding was the most desirable outcome. And there are moments in Bruce Norris‘ fiercely funny play about race, real estate, and the evolving urban environment, when that absolutely seems to be the case. It sometimes becomes so busy, frustrating and noisy it might as well be Congress.

Clybourne Park‘s well known central conceit is that it functions as a sequel to Lorraine Hansberry‘s groundbreaking 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun. The first act occurs simultaneously with the actions of Raisin, but in the tragedy-haunted home Hansberry’s Younger family will eventually buy. The white middle class sellers are packing up for the suburbs and as they prepare, physically and emotionally, to move away from the place where their son took his own life, they are visited by a neighbor, Karl Linder, the only character to appear in both Raisin and Clybourne Park. He’s come with his deaf wife in tow, to announce that the family that has bought the house—a house already devalued by suicide—is black. He explains, with increasing frustration and anger, all the reasons why this new development will have a devastating effect on the neighborhood and the value of his property.

Flash forward 50 years. For being so wrong Karl was correct in his predictions. As foretold, white families moved away from Chicago’s once desirable Clybourne Park. Well, at least the people who were capable of moving. Over time it became a black, down-at-heel neighborhood that has since stabilized and is now on the cusp of gentrification.

The graffiti-covered Younger house is now empty and a young white family is hoping to tear it down and erect a new home that’s 15-feet taller than anything in the neighborhood. They are being opposed by a neighborhood group, and Norris’s depiction of the negotiations over demolition may be the most eviscerating depiction of privilege and modern tribalism to appear on this, or any stage. Everybody, justified or not, has their own persecution complex, and offense is the default response to nearly every circumstance.

Norris’s sharp writing doesn’t just expose overt prejudice on all sides, it also digs into the white liberal value system to expose more subtle and insidious strains of racism that can’t be easily recognized or understood without an unusual degree of self reflection. We’ve all seen it. It’s the kind of racism that invariably leads a person to remind other people that some of his/her best friends aren’t white. Norris addresses all of this so honestly and with such biting humor that even thinner-skinned audience members who might be caught up in their own privilege and inclined toward easy offense, will be too busy laughing to get mad.

Director Stephen Hancock has assembled a top drawer cast of character actors for Clybourne Park’s regional premiere. John Maness is superb as Karl, the kinder gentler 50’s-era racist. He’s even better as Steve, a successful progressive who has suppressed his “white man’s burden” as long as he can, and isn’t going to take it anymore.

Maness’ telling of an off color joke is a brilliant exercise in uncomfortable anti-humor. And it frees up other players in this too familiar drama to share their own culturally-charged jokes.

How is a white woman like a tampon? I’m not saying, but there it is.

Recent Ostrander winner Claire Kolheim proves once again that she is one of Memphis’ finest, playing a soft-spoken maid and an outspoken attorney. The always excellent Michael Gravois is convincing as a 50’s era businessman devastated by the loss of his son and also as a talkative laborer who finds a chest buried in the back yard. Meredith Julian gives a fearless performance as the potentially offensive hearing-impaired racist’s wife then turns the tables as an easily offended yuppie who isn’t deaf but still seems to have a hearing problem.

Clybourne Park is, in every way, an ensemble show but somehow, and in spite of her not being especially tall, Mary Buchignani Hemphill stands head and shoulders above the rest of the cast. In act one she is the stereotypical mid-century housewife, happy to not have a mind cluttered with all the pesky information that trouble the menfolk. If knowledge is power she’d rather be powerless. Hemphill disappears into the character.

In act two Hemphill plays the middlebrow daughter of Karl Linder, who is now a real estate agent. And she does so with such confidence and comfort it’s easy to forget she was also the crumbling hysteric from act one.

We’re only two months into the 2013-14 theater schedule and already Memphis theatergoers have had an opportunity to see some extraordinary dramatic productions. Red at Circuit Playhouse, Proof, at Theatre Memphis, and The Whipping Boy at Hattiloo were all shows that could be a highlight of any season. Of them all, Clybourne Park is the most provocative and the most entertaining. It’s exploration of tribal codes and loaded language might even lead one to suspect that all the fighting happening in the U.S. Congress right now isn’t really about the budget, or the deficit. It could be about a certain piece D.C. of real estate— a white house, if you will— and who is and isn’t allowed to occupy.

For details click here.