“Anthropologists are thrice-born,” my old instructor in the discipline, T.O. Beidelman, once asserted in a lecture. He had us all captivated with his tales of fieldwork among the Dinka in the Sudan. “First, we are born into our own culture. Secondly, we enter the cultures we study as children, and gradually are born as social beings in that community. And thirdly, we are reborn when we return to our own culture, seeing it with fresh eyes.”

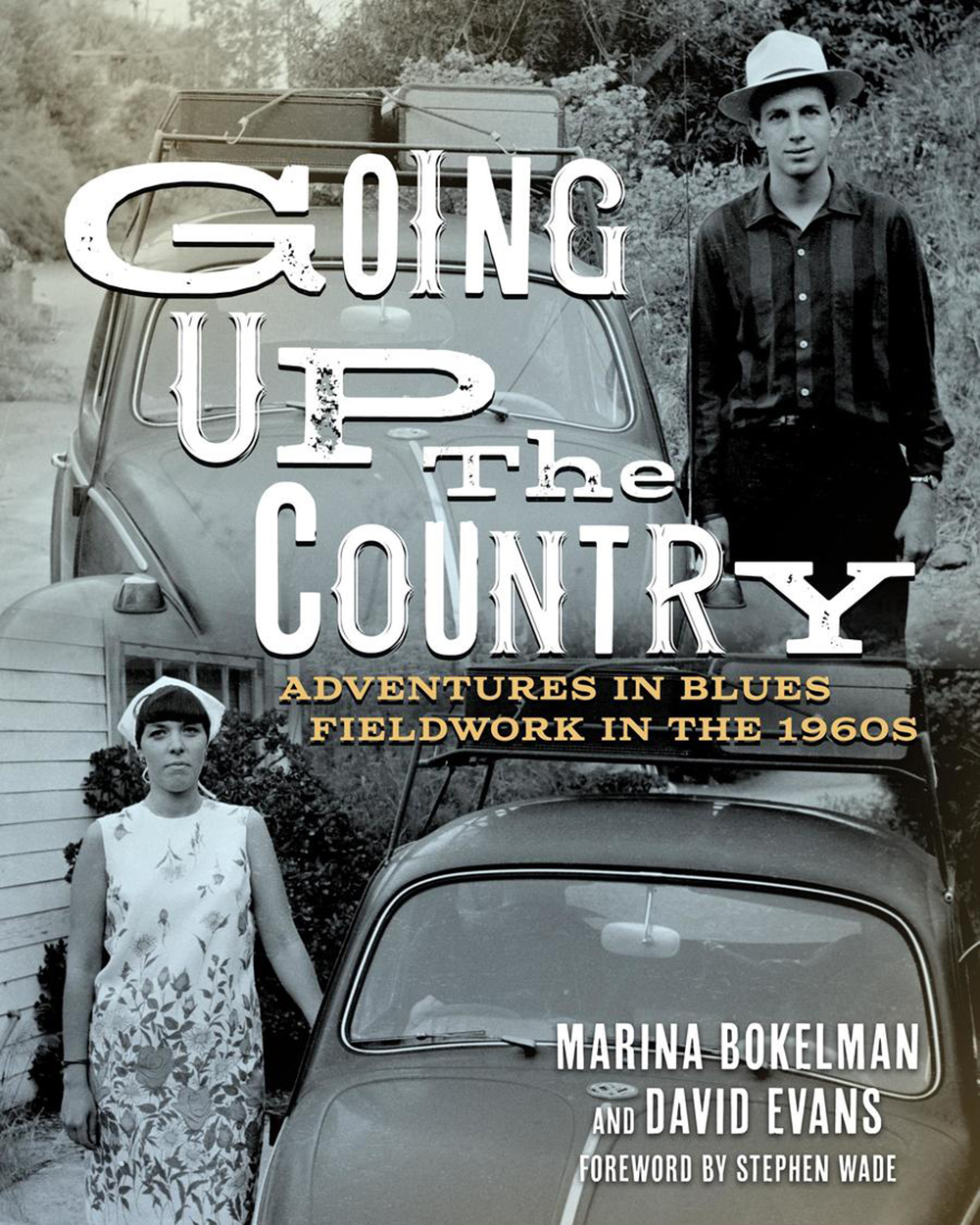

Those words have echoed in my mind while reading a stunning new collection of field notes from the ’60s by two graduate students — one of anthropology, the other of folklore/ethnomusicology — in the blues communities of Mississippi and Louisiana. Going Up the Country: Adventures in Blues Fieldwork in the 1960s (Univ. Press of Mississippi) evokes all the excitement of discovery, of being reborn into another culture, that only a person putting their life and time on the line can feel as they aim for complete immersion. And it’s especially gripping for Memphis-based music lovers, as one of the authors is David Evans, onetime director (and founder) of the ethnomusicology program at what is now called the University of Memphis.

His time at the university is highly regarded among blues aficionados, for he not only studied the form but also performed it (often with the legendary Jessie Mae Hemphill) and produced it, running the small High Water Records label with Richard Ranta, which released many singles and a few albums by lesser-known artists in the ’70s and ’80s. Now retired, he’s still a performer and an appreciator of the blues. Yet all he accomplished at the University of Memphis is but an afterthought in this work, which focuses on earlier chapters of Evans’ life. But he wasn’t alone then.

“It was co-authored with my friend at the time, Marina Bokelman,” Evans explains, noting that Bokelman passed away in May of last year at the age of 80. This book is a fitting tribute to the magnificent work the two did over a half century ago. “We focus on the fieldwork that we did in 1966-67,” Evans adds. “It’s based on the field notes that we took as we did the work. Each day we’d write the notes, describing what we did, our encounters with artists and others. And then there are some other chapters providing background on that, discussing fieldwork, and a little bit about our lives before and after that period.”

The core of the book is an evocative tour through the lives of blues and gospel singers, with a level of detail and attention to both the music and their lives rivaling any blues study before or since. The co-authors’ notes and photographs take the reader into the midst of memorable encounters with many obscure but no less important musicians, as well as blues legends, including Robert Pete Williams, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Babe Stovall, Reverend Ruben Lacy, and Jack Owens.

It was all part of the authors’ studies in the fledgling folklore and mythology program at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), where they began dating. There was clearly an intellectual as well as a romantic bond there, and the scholarly standards of the field notes are high. But this is also an adventure story of sorts, as the young couple describes searches for musicians, recording situations, social and family dynamics of musicians, and race relations, not to mention the practical, ethical, and logistical problems of doing fieldwork. The book features over one hundred documentary photographs that depict the field recording sessions and the activities, lives, and living conditions of the artists and their families. As you read along, you’ll want to listen to any recordings of the artists that you can get your hands on.

While the field adventures are gripping, so too is the milieu of the young scholars in Los Angeles at the time, living in Topanga Canyon, and playing host to a young Al Wilson, with whom Evans performed previously in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Evans describes introducing Wilson to Tommy Johnson’s “Canned Heat Blues,” and we read of Wilson founding the famous group named after that 1928 record. With this section, occupying nearly the first hundred pages of the book, and the “after the field” biographical essays detailing the authors’ lives after splitting up and pursuing their respective passions, this book is a glowing portrait of two insatiably curious souls, a fitting memoir of two lives well-lived.

“We had some real adventures,” reflects Evans. “They’re all in the book.”