When Marisol Escobar premiered her 1969 sculpture The Family at the Brooks Museum of Art, it stirred up a lot of local controversy. “The Family is a work to be contemplated and meditated on,” wrote the art critic for The Commercial Appeal, “no matter how much it hurts you to look.”

The controversial works by Marisol.

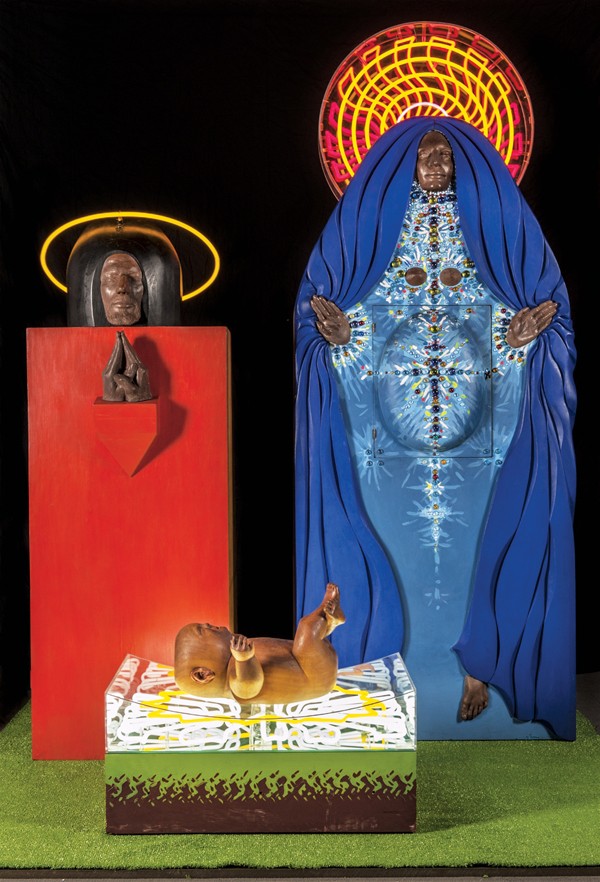

Viewers were cautioned that The Family, the Brooks’ first-ever commissioned work, is an unorthodox depiction of the Virgin Mary, Jesus, and Joseph. The three figures all wear neon halos and are painted in bright, Popish colors. And if those details didn’t rile museum visitors, Marisol’s infant Jesus is, ahem, anatomically correct. In a segment on the work, WMC Action News 5 cautioned museum visitors that “we’re used to halos and heavenly light being represented by paint and gold and silver — but not by the more effective neon tubing.”

After many years in storage, The Family is now on display at the Brooks as part of an expansive retrospective of Marisol’s (she rarely used her last name) work. It is the entry-point to the story of Marisol, an avant-garde female artist who moved lithely between genres and styles in 1960s Greenwich Village and whose career has often been understated in the cultural memory of the era. Marisol was a sculptor, printmaker, and draftsman, a Warholian It Girl, a social critic, and feminist who sometimes disowned her own sharp-eyed criticism in favor of maintaining a mysterious presence.

The retrospective, which opens June 14th, is the summation of 10 years of effort by curator Marina Pacini, who began her work with Marisol around the time she joined the Brooks. Pacini’s mission is to give Marisol’s work the space and attention it is due. Says Pacini, “This is an amazing model of a very successful woman artist who was making works on her own terms.” The exhibit is the first of its kind — a definitive look at an artist whose long history with Memphis is, four decades after The Family‘s debut, finally getting proper context.