Most barbecue restaurants have a cartoon pig logo — a dancing pig, a cool pig in sunglasses, a pig in a chef hat. Some restaurants even have a pig statue as a mascot. But Baby Jack’s BBQ owner Will Clem envisions someday having a live pig as a mascot — the same pig where the meat served in his Bartlett restaurant would come from.

“The animal could stay there and be the spokesperson, the mascot. You could point to him and say, ‘That’s where your meat came from.’ We could have a pig mascot, and he’d still be alive,” says Clem, who opened Baby Jack’s on Summer in 2012.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Clem opened Baby Jack’s BBQ in 2012.

No, they wouldn’t be slicing cuts of meat from a live pig. What Clem is suggesting is growing meat in a lab using a few of the pig’s cells. It sounds like science fiction, but Clem also has a background in tissue engineering, and, when he’s not busy running a barbecue restaurant in Bartlett, he’s part of a team of scientists at Memphis Meats, a San Francisco-based tech start-up that is growing meat using cells extracted from from live animals.

The Memphis Meats team prefers to call their product “cultured meat” rather than “lab meat,” and it’s grown in incubator tanks over a period of weeks. They say the end product looks and tastes exactly like meat from a slaughtered animal, but the animal doesn’t have to die, and the process is more environmentally sustainable than conventional farming.

“The global demand for meat is increasing significantly over the next 30 years. It will double by 2050, and that’s a much faster pace than the current meat industry can sustain,” says Uma Valeti, the CEO and cofounder of Memphis Meats. “Much of that is related to scarcity of resources and how much land, water, and energy it takes to grow one pound of meat, whether that’s beef cattle or a different meat.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Will Clem points to the new blank menu at Baby Jack’s, where prototype products may be featured.

Memphis Meats’ prototype product is a beef meatball, and they say hamburgers, sausages, and hot dogs are next. But Clem envisions someday being able to serve Southern-style smoked pork sandwiches made from cultured meat, and he’d even like to tackle baby back ribs — bones and all. Memphis Meats was only founded a few months ago, and they expect it will be several years before their products are cost-competitive enough to bring to market. But Valeti says that day is coming.

“We’re building a new type of agriculture, and I see the current meat production industry embracing it because this is a way for them to feed the masses in the future and introduce some innovation into an industry that hasn’t seen innovation for centuries,” Valeti says.

Courtesy of Memphis Meats

Courtesy of Memphis Meats

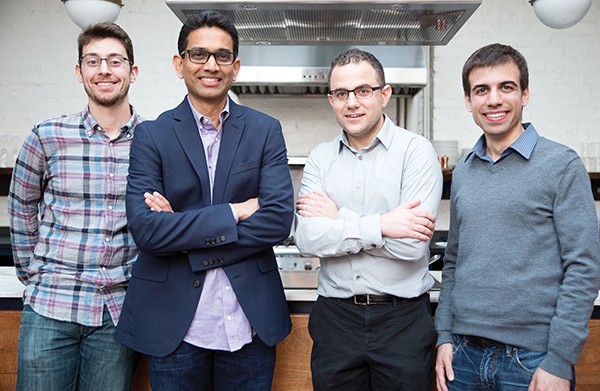

(L to r) Morgan Reese, Uma Valeti, Nick Genovese, and David Kay

From Memphis to San Francisco

Memphis Meats may have “Memphis” in the name, but the actual work is being done in San Francisco. They chose the name Memphis Meats as a way to pay homage to Memphis’ barbecue culture.

“We wanted to bring the strength of innovation from Silicon Valley and the meat-loving culture of Memphis together,” says Valeti, a former cardiologist.

Clem, one of the company’s cofounders and tissue engineers, is the local tie. He grew up in Alabama, surrounded by barbecue. His grandparents founded the Whitt’s Barbecue chain, which grew to more than 40 locations around the South. But the young Clem was drawn to the science world and went off to the University of Michigan to earn his master’s degree and then the University of Alabama at Birmingham for a PhD in tissue engineering.

He wound up in Memphis with a career as a human tissue engineer for Wright Medical. But Clem couldn’t resist the siren song of barbecue, and he soon found himself back in the restaurant industry. He opened Baby Jack’s (named after his younger son) in 2012 as a side project, but business picked up so much that he eventually left Wright Medical to operate the restaurant full-time.

He was drawn back into the science world, though. Last fall, he got a phone call from an old college friend, Nick Genovese, another of Memphis Meats’ cofounders.

“I met Nick when we were in business school in Birmingham in 2007 or 2008. He was already talking about this cultured meat idea back then,” Clem says. “Fast forward about 10 years, and I’m carrying boxes into the restaurant. We’d just signed a lease on a second store in Arlington, and we were two to three weeks from opening it. And Nick calls and says, ‘Well, I’m ready. Let’s start that cultured meat company.'”

Clem dropped everything and was on his way to Minneapolis, where Genovese and Valeti were, the next day. The Memphis Meats project was so important to Clem that he had to put the Arlington Baby Jack’s opening on hold, and he also left his son Nathan, who was 4 months old at the time, and wife behind in Memphis.

The team — Valeti, Genovese, and Clem — formed a business plan and proposal and applied to IndieBio, a business incubator in San Francisco. They were accepted into the four-month program, so they headed to California to get started on developing a cultured meat prototype. By “demo day” — when all the incubator participants pitch their businesses to investors — on February 4th, they’d already secured $2.75 million in funding, which exceeded their goal of $1.5 million.

Much of that money is coming from New Crop Capital, which, according to its website, “invest[s] in talented, focused entrepreneurs whose products or services replace foods derived from conventional animal agriculture, which we view as an antiquated and inefficient food production system with serious vulnerabilities.”

Bruce Friedrich is the managing trustee of that venture capital firm. Friedrich also serves as the executive director of the nonprofit Good Food Institute, which provides strategic support and promotion for companies working on cultured meat products and plant-based meat, milk, and egg products.

“They are creating meat that tastes the same as the meat from farmed animals, but this is more sustainable,” Friedrich says about why his firm got behind Memphis Meats.

Genovese knows a thing or two about conventional farming. The stem cell biologist grew up on a poultry farm, helping his family raise chickens, before going on to become a bioprocess technician with a doctoral thesis in cancer biology. The self-professed meat-lover is now a vegetarian pioneering more sustainable ways to produce meat.

Valeti is a former cardiologist, and he says growing cultured meat isn’t unlike the work he used to do in the medical field. “We use cells to regenerate heart muscle in patients who have had heart attacks. If we’re injecting cells into the hearts of humans to grow new muscle, why couldn’t we apply the same technology to growing meat?”

How It’s Made

What Memphis Meats is doing with cultured meat isn’t unlike what Clem was doing with human tissue in his Wright Medical days or what Valeti was doing with his heart patients. “You start with a small number of cells, even just a single cell taken from the muscle. That can be pork, beef, chicken, or you can be really fancy and have some type of exotic meat, like lion or something. Who knows?” Clem explains. “We multiply those cells in incubators, and you can turn a few cells into many. It takes about one to three weeks.”

The meat is grown in tanks that Clem says are similar to something you’d see in a craft beer brewery.

“A lot of restaurants have a beer tank in the corner, and they’re brewing an IPA. Well, this is the same thing, only it’s growing beef, pork, or chicken,” Clem says.

Friedrich furthers the the craft beer analogy by envisioning a day when people can tour cultured meat factories.

“One of the selling points of cultured meat is that, because it’s brewed in fermenters, there is total transparency,” Friedrich says. “Right now, good luck getting into a modern farm or slaughterhouse. Other than a few free-range operations, the vast majority of farms are not good experiences, and that’s true for all slaughterhouses. But you could take a tour of a cultured meat factory, just like you can tour a brewery.”

The slaughterhouse is completely out of the equation for cultured meat, since the cells can be taken from a minor biopsy procedure. The animal doesn’t have to die, and for the consumer, there’s less risk of contamination.

“From a health perspective, there are a number of risks in how meat is produced. There are antibiotics pumped into animals raised in confined spaces,” Valenti says. “And, even with grass-fed animals raised organically on free-range pastures, there is a risk of fecal contamination and bacteria in the process of slaughter. There is also less risk of epidemics, like swine flu and avian flu, that are occurring because of how meat farming is done these days.”

The cultured meat process uses far less resources than factory animal farming, making it an environmentally sustainable alternative. To feed the global demand for meat, the current system often requires deforestation to make way for grazing land, and mass quantities of water are used to grow the crops used to feed livestock, he says.

“It takes about 23 calories of grain to make one calorie of beef. We love meat, but at the same time, we can’t sustain to produce it,” Valeti says.

Culturing meat releases 90 percent less greenhouse gas emissions than traditional factory farming, Valeti says, meaning it has far less impact on climate change.

Cultured meat is also much safer, Clem says, since it’s created without bacteria.

“If I have a pound of hamburger sitting on the table, everybody knows that’s hazardous. You can get food poisoning from raw meat, and you have to cook it to kill the bacteria,” Clem says. “But cultured meat is aseptic. It’s made without bacteria, and there’s no chance of food poisoning. The safety of it is a huge advantage.”

But how does it taste?

“I would say it’s indistinguishable. I wouldn’t say it’s better or worse than meat. It’s the same thing,” Clem says. “A lot of companies in San Francisco are trying to make meat alternatives, like with tofu and things, and it’s pretty tough to make those [foods] taste like meat. But the advantage of this is it is meat. We don’t have any formulation to do. We just take our traditional recipes and cook them the same way our grandparents did.”

Memphis Meats employed a chef to create an authentic Italian meatball with their prototype beef. A video on their website shows the meatball frying in a pan, and a tester who tries a bite reports, “It tastes like a meatball. It’s good.”

Meat of the Future

It may be a few years before consumers can decide for themselves how cultured meat tastes. First, Memphis Meats has to get the price down to a reasonable level. The first meatball cost the company $18,000 to produce, but they say that included the start-up costs.

“The first iPhone cost millions of dollars to produce. The first TV probably cost a ton to produce. The first of anything costs a lot of money,” Friedrich says.

The company has a goal of getting cultured meat to market in five years, but at first, it still may cost a bit more than conventionally produced meat. However, in 10 years, they say it should be price-competitive or even cheaper than meat produced from slaughtered animals.

“That could happen much more quickly if, say, Bill Gates decided that he wanted to put some resources into this. It’s really just a function of time and money,” Friedrich says.

Winning Gates’ support isn’t unfeasible. The billionaire business magnate has already invested in at least two plant-based meat and dairy start-ups — Hampton Creek (maker of the vegan Just Mayo spread) and Beyond Meat (which creates plant-based chicken and beef alternatives).

Thanks to Clem’s involvement, Memphians may get the first taste of Memphis Meats’ products. Friedrich said he thinks a few prototypes may be available in Clem’s restaurant in about three years.

“We installed a blank menu [at Baby Jack’s BBQ] to prepare for it. It’s been a conversation starter, and we’ve been telling our customers about our Memphis Meats story,” Clem says. “Hopefully, we can start bringing some prototypes here, and we can cook them up.”

Those early prototypes will include the meatball, as well as hamburgers, hot dogs, and sausages. Clem says they’ve started with those ground meat products because they’re easier to produce at a benchtop scale, but as the operation grows, he says the sky’s the limit for what they can produce. Clem has experience growing human bone at Wright Medical, and he says that same process could be used to grow animal bones for cultured pork ribs or chicken wings.

Although the team expects some ethical vegetarians and vegans — those who choose not to eat meat because an animal has to be slaughtered — will consume their products, the target customers are the meat-eaters who are interested in safer, more sustainable meat.

Because of that, Memphis Meats is growing cultured meat with the exact same fat content of conventionally farmed meat.

“Since it’s an identical product, the health concerns associated with meat will still be there. Cultured meat is safer and more sustainable, so that’s the focus,” Friedrich says. “Once we’re mass-producing an identical product, there may well be a market for changing some of the nutritional components without changing the taste. But right now, our focus is a cleaner, more sustainable alternative to animal agriculture.”

Culture It and They Will Come?

Perhaps the biggest question facing Memphis Meats is whether or not there’s a market for cultured meat. Will people eat it? Will the science freak them out?

The Flyer took an informal Facebook survey of Memphis eaters, and responses were all over the board.

“As a non-vegetarian and avid sci-fi guy, I’d totally eat it,” wrote James Sposto, a local entrepreneur and producer of the FOMO Fest music festival. “Cells are cells, and cultured meat would taste the same as regular meat without the cruelty or environmental impact. Do you have any idea how much methane cows produce? Huge greenhouse gas emitter. And pigs are smart as hell.”

Cooper-Young resident David Rupp agreed with Sposto in fewer words: “Fire up the grill,” he wrote. And Jason Hodges, a St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital employee, wrote that he would try it since “it can’t be any worse than anything else I’ve ever consumed.”

But others just couldn’t stomach the thought of eating meat grown in a lab. Yoga teacher Tammy Dingman says she can’t “wrap her head around meat processed from cells.” Political writer Cheri DelBrocco wrote that the whole idea seems “very Twilight Zone-y” and that she didn’t think she’d eat it.

Chef Gary Williams, who owns DeJaVu Restaurant, says he just isn’t sure about cultured meat.

“I would need more research, more proof. This is a different beast,” Williams says. “I’d have to see it in front of me and look at the texture. I would just need more information.”

One well-known chef who asked to remain anonymous said the science would be “great if we find ourselves in a world food crisis, but I could never see a scenario where, when people have a choice, they would go into a restaurant and ask for the spaghetti and meatballs grown in a test-tube.”

A few local vegans and vegetarians have weighed in as well. Some say, although they support the idea of producing more sustainable meat, they personally wouldn’t eat it.

“I wouldn’t eat it because, after almost a decade of veganism, I’ve lost my taste for meat. But I’m very excited about this. If it reduces animal suffering, I’m all for it,” local vegan Tiffany Lindfield wrote on Facebook.

Kristie Jeffrey, who owns Imagine Vegan Cafe, expressed support for the idea but said she wouldn’t eat cultured meat.

“I’m comfortable with where I am, and I don’t have any desire to eat anything that came from an animal again. But I would encourage meat-eaters to try it. Factory farming has to end somewhere, and I would love to see that happen in our lifetime,” Jeffrey says.

Other vegetarians and vegans couldn’t get over the sci-fi factor.

“You’re playing God, and I don’t agree with that. It sounds like a science experiment, and my body isn’t a science experiment,” says Cassi Conyers, who owns the vegan bakery and restaurant Pink Diva Cupcakery.

Valeti said meat-eaters who label cultured meat as “franken-food” or “test-tube meat” should be reminded that “there is nothing natural about the current meat that is available on the market.”

“There’s nothing natural about chickens being grown six to seven times larger and faster than in nature. There’s nothing natural about packing 1,000 pigs in a feces-filled barn and pumping them with antibiotics. There’s nothing natural about growing turkeys to be so top-heavy they cannot stand up to breed,” Valeti says. “We need to rethink what is considered natural and not natural.”

Cultured meat may have been considered science fiction 20 years ago, Valeti says, but it’s real now. Besides Memphis Meats, three other companies in New York, Israel, and the Netherlands are also working on getting cultured meat to the masses.

As for Memphis Meats, Clem says they’re currently recruiting some of the world’s leading scientists to help them scale up production, and they plan to run the business from San Francisco for the foreseeable future. Clem will continue to travel back and forth from Tennessee to California as needed, but over the next couple of weeks, his full attention will be directed elsewhere.

Remember that second location of Baby Jack’s he put off opening to go work for Memphis Meats? It’s opening in Arlington “any day now,” he says.

“Hopefully, this is the first expansion of many,” Clem says. “We are planning to cover the city of Memphis in Baby Jack’s. We’ll have one on every street corner.”